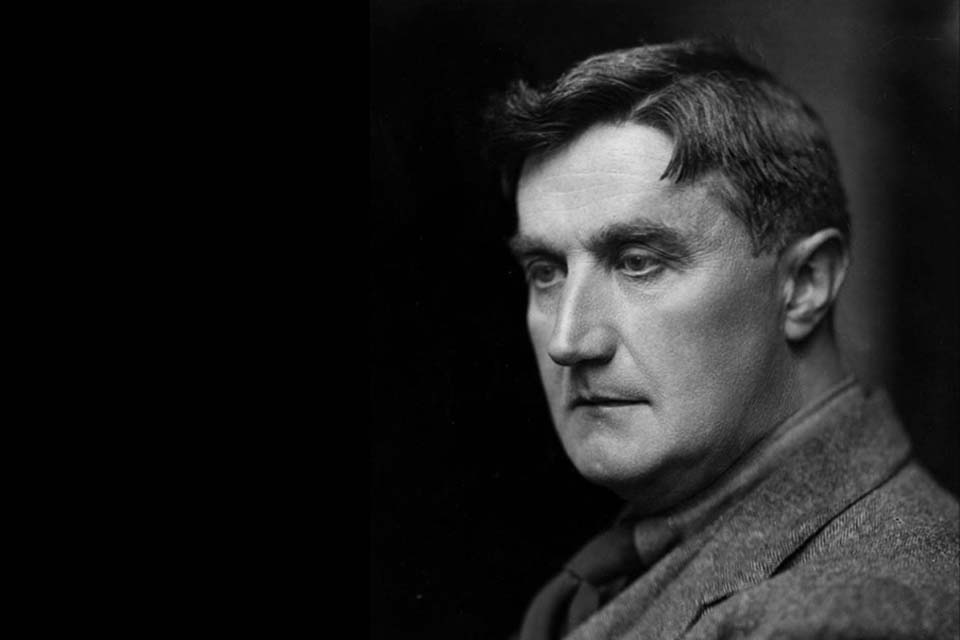

Vaughan Williams: another perspective on the quintessentially British composer

Share #UpbeatOnline

2022 marks 150 years since the birth of the most quintessential of British composers, Ralph Vaughan Williams. Although he’s most widely celebrated as a composer, Vaughan Williams also dedicated much of his life to teaching, including 20 years on the RCM Composition Faculty from 1919 to 1939.

Professor David Wright, RCM Professor of the Social History of Music, explores just how important an influence Vaughan Williams was for his students, particularly his resolute support for women composers – and how his liberated approach helped shape the musical landscape in Britain.

Singer and comedienne Anna Russell, once celebrated for her comic musical sketches, wrote vividly about being taught by Vaughan Williams. In her autobiography, she remembered: ‘He was a great big countrified-looking old gentleman who was kind and charming. He said my compositions weren’t bad, but very derivative. “For instance”, he said, “that one is quite a creditable piece of Debussy”.’

‘This got to be rather a joke. “Who are we going to be today?”, he’d ask. “Mozart or Wagner?” One day he asked me to please restrain the urge to be Gilbert and Sullivan, as he found himself humming my pieces, which interfered with his own musical thinking. After that he always referred to me as “Gilbert and Sullivan Russell-Brown”.’

There was a certain prophetic element to all this, for some of Russell’s most famous acts would include the humorous 20-minute synopsis, The Ring of the Nibelungs (An Analysis) and the parodic How to Write Your Own Gilbert and Sullivan Opera.

One reason why Anna Russell’s reactions are so revealing is that she only went to study with Vaughan Williams because her first composition teacher, Herbert Howells, had thrown her out – so strong was his contempt for her music, which he considered only fit for ladies’ tea parties.

[image1]

The search for musical identity

Just how far Vaughan Williams sought to distance himself from Stanfordian composition is clear from his decision (after compositional success and at the surprisingly late age of 35) to take lessons from Ravel – a mentor as dissimilar to Stanford’s precepts as it is possible to imagine.

Vaughan Williams’ prolonged search for his true compositional identity seems key to the supportiveness and encouragement he showed to similarly questing students. Discussing Vaughan Williams’ musical apprenticeship, musicologist Byron Adams makes the important point that the composer was carefully concealing about the technical refinements he assimilated from Ravel.

As Adams details, these developments were not confined to exercises in orchestral sound and textures, but extended to the modal techniques Ravel had absorbed from Borodin, Mussorgsky and Rimsky-Korsakov, and which would subsequently appear in some of Vaughan Williams’ own works.

Encouraging independence

The open-mindedness of Vaughan Williams’ own musical thinking explains much about his teaching gifts, and certainly his students remembered him with great warmth.

The composer Elizabeth Maconchy said that it was difficult to describe Vaughan Williams’ teaching in precise terms because he never sought to apply ‘ready-made’ formulae. Instead, he encouraged his students to work out their own ‘salvation’ (his term) to resolve compositional dilemmas.

Making students think for themselves about the potential and limitations of their musical ideas helped them to achieve true compositional independence. Tellingly, three of Vaughan Williams’ women students won the prestigious RCM Octavia Travelling Scholarship: Dorothy Gow and Grace Williams to study with Egon Wellesz in Vienna, and Elizabeth Maconchy (enthusiastic about Bartók and Janáček) with Karel Jirák in Prague. Interestingly, Benjamin Britten, another Octavia scholar, was to be thwarted in his ambition to study with Berg.

[quote quote="Vaughan Williams’ efforts on behalf of young British composers went well beyond just those individuals whom he taught." author=""]

Mentorship beyond the classroom

Vaughan Williams’ commitment to the cause of British composition is evident from a 1912 article written for the RCM Magazine, ‘Who Wants the British Composer?’ There, he squared up to the reality that British composers then were ‘unappreciated at home and unknown abroad’, and throughout his life he worked to change that situation.

[image2]

Vaughan Williams’ efforts on behalf of young British composers went well beyond just those individuals whom he taught. He generously used his influence to have unknown composers’ works programmed – essential to come to a publisher’s notice – and enthusiastically supported enterprising ‘self-help’ schemes.

One of the most remarkable of these was the London-based Macnaghten-Lemare concert series, whose six seasons ran from December 1931 to February 1937. Musicologist Sophie Fuller’s invaluable account of these concerts underlines the sense of a new mood being generated amongst this young generation of performers and composers (including Elisabeth Lutyens, Elizabeth Maconchy, Imogen Holst, Benjamin Britten, Michael Tippett, Grace Williams and Dorothy Gow), all eager to break through and overcome the BBC’s scant interest in them.

The instigators of these concerts were two RCM students, the conductor Iris Lemare and the composer Elisabeth Lutyens, together with the violinist, Anne Macnaghten, who had studied privately with Jelly d’Arányi and at Leipzig Conservatoire. As Macnaghten explained, ‘recognizing the common needs of unknown composers and players, we set about making common cause’.

And so, the Macnaghten-Lemare concerts were set up as something of a cooperative, working on the basis of mutual help in copying performance materials, commitments to sell a number of tickets and of minimal fees and expenses. In all of this, Vaughan Williams was stalwart in his support and attendance as his correspondence makes clear, bringing along publishers and critics and writing that the enterprise of these concerts was ‘putting the BBC and [Thomas] Beecham to shame’.

RCM’s support for women musicians

It is striking to see how many successful women performers and composers were being trained at the RCM. Quality of musical talent did much to ensure gender equality in the student body, but the sticking point often came when women sought to enter the professional sphere. This was because women musicians were perceived to pose an economic threat to the traditional expectations of male wage earners, especially in the economic depression of the 1930s. (Talking pictures was just one form of mechanization that had put many thousands of musicians out of work.)

But the opportunities women students had established for themselves at the College were significant in encouraging women to mark out their place in the profession. One notable woman-organized society generated out of the RCM was the Society of Women Musicians, founded in 1911 by two College students, Gertrude Eaton and Marion Scott (the musicologist and long-time editor of the RCM Magazine), with Emily Eggar.

The Society sought to advance the work of women musicians, including by applying the pressure needed for the ABRSM to appoint women examiners in 1956, thereby righting both an economic injustice and correcting the canard that only male musicians had the status to be examiners. The example of the SWM could well have helped encourage the creation of the Macnaghten–Lemare venture.

Although its organizers distanced themselves from any specifically feminist aims, Fuller makes the telling point that the success of the Macnaghten-Lemare concerts for composers of both genders reflected the fact that they were women-centred, emphasizing acts of cooperation that were ‘outside the box and beyond boundaries’. She contrasts their evident achievements with the less successful Adolph Hallis chamber concerts, run on more traditionally male-dominated and committee-organised lines.

A lasting influence

In various important ways, the British musical environment of the 1920s and 1930s had become a very different world from the one Vaughan Williams had outlined in that 1912 article. Vaughan Williams had played an important personal role in that change, both in terms of his liberated approach to teaching composition, but also as a force for good in securing opportunities for young British composers to have their voices heard.