In October 2022 the Dartington Summer School Foundation donated to the British Library the archive of Summer School papers and images curated by Jeremy Wilson. This has allowed the Royal College of Music’s Music, Migration and Mobility team to study another lasting post-war British institution in which migration and mobility have played a central role. Like Glyndebourne and the Edinburgh Festival, the original inspiration for the Summer School came from a central European émigré – in this case the pianist Artur Schnabel – and many other émigrés were crucial to its success, forming a bridge between cultures divided by war and establishing musical standards far in excess of what was normal in Britain at the time.

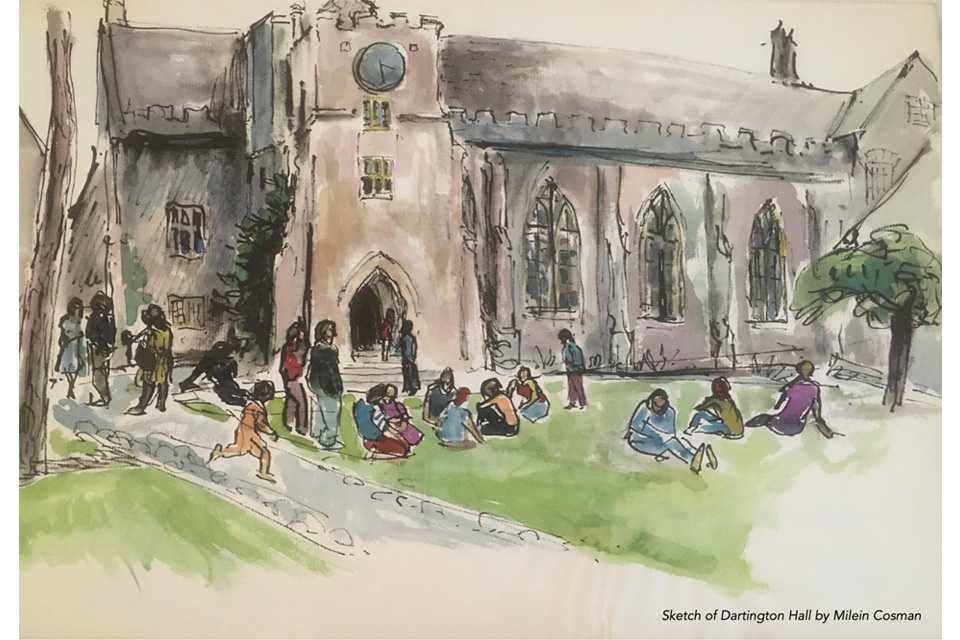

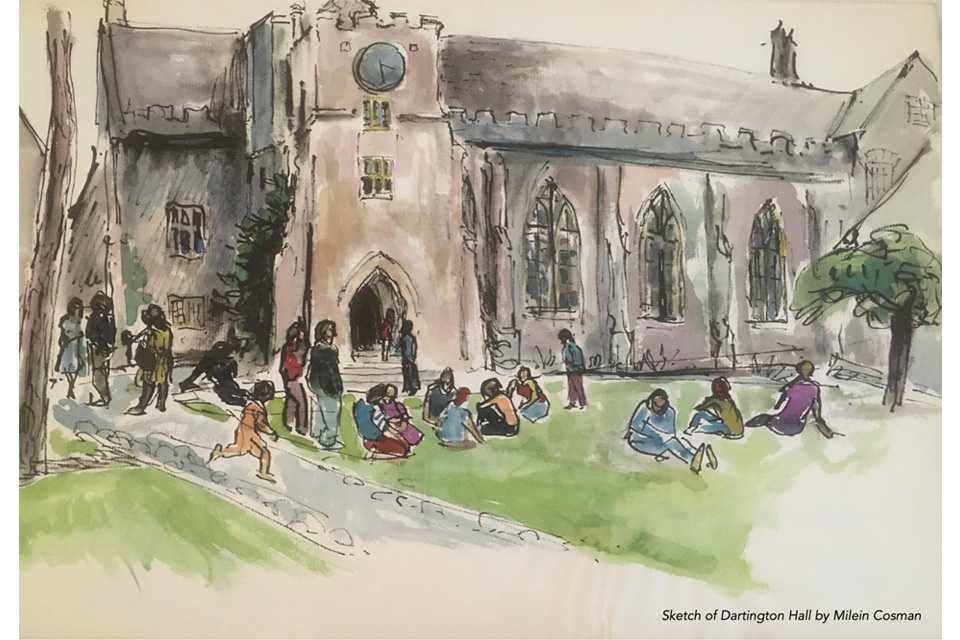

The archive collected by Jeremy Wilson allows a detailed view of how diverse musicians interacted and developed their ideas – which music was played and composed, how ensembles were formed and developed, and the impact made by great musicians visiting from around the world. Jeremy Wilson was himself involved with the Summer School almost from its beginning, and in 1992 he began a concerted effort to preserve as much as possible of its history, assembling a complete set of programmes, together with the correspondence and papers of key figures like William Glock and John Amis. Supplementing these written materials is an extensive collection of photographs by Summer School photographers Catharine Scudamore (who took the majority of the images featured on this page) and Charles Davis, giving a vivid sense of the remarkable musical community gathered at the Summer School each year. Another rich visual memory of the Summer School is found in the drawings of Milein Cosman, the German émigré artist who came to Dartington every summer for decades, her sketchbook always at hand: over 1,300 of her portraits of musicians are held in the Milein Cosman Collection in the Royal College of Music Museum, with additional sketchbooks from her years at Dartington preserved in her personal archive at Tate Archive.

The story below gives a flavour of the creative cosmopolitan world of music at Dartington, with full details of the Summer School’s earliest years available via the RCM’s new Dartington database.

‘A Window on the World’: the Dartington Summer School of Music

Author: Alison Garnham

‘A window on the world par excellence!’ is how the young British pianist and composer Susan Bradshaw described her first visit to the Dartington Summer School of Music in the early 1950s. ‘It was a truly mind-blowing experience in every way, and I still remember the heady excitement of trying to savour everything on offer in the action-packed days.’[1]

Founded in 1948, and held initially at Bryanston School in Dorset before it found its permanent home at Dartington, the Summer School of Music was the most exciting and imaginative music education institution in post-war Britain. In contrast to the rather narrow horizons of the principal British conservatoires of the day, the Summer School was determinedly international from the start, bringing great musicians from around the world to teach and perform, including many of the talented émigrés now living in Britain. After the isolation of the war years, this exposed young musicians here to a standard of music-making and breadth of musical ideas of which most were previously unaware.

The range of repertoire at the Summer School was also remarkably broad for the times. Concerts and lectures featured music from the fourteenth century to the present day, with widely differing periods and styles often programmed side by side. You can explore the full details of the music and personnel of the Summer School’s earliest years in the RCM’s new online database.

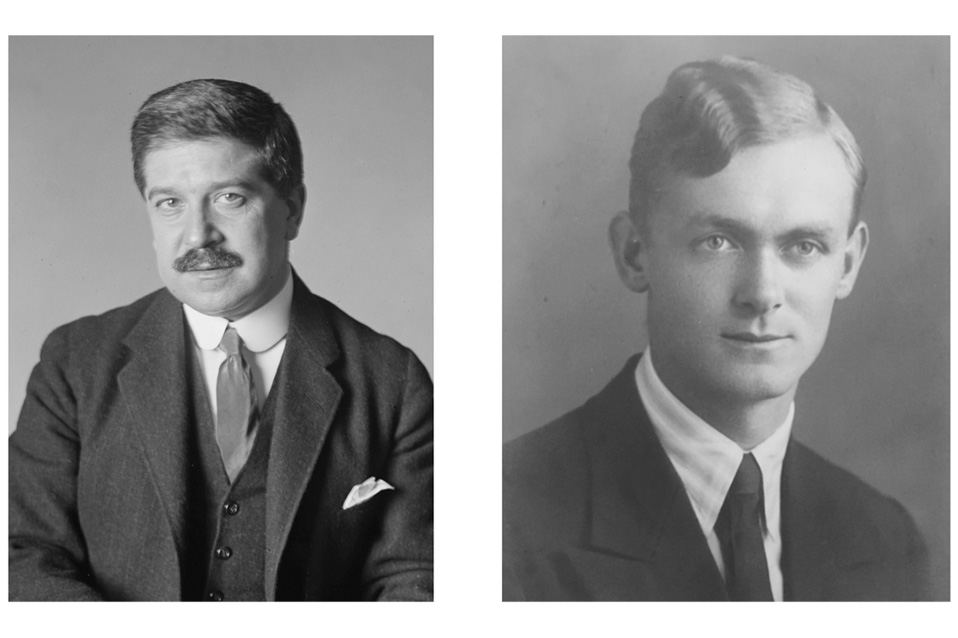

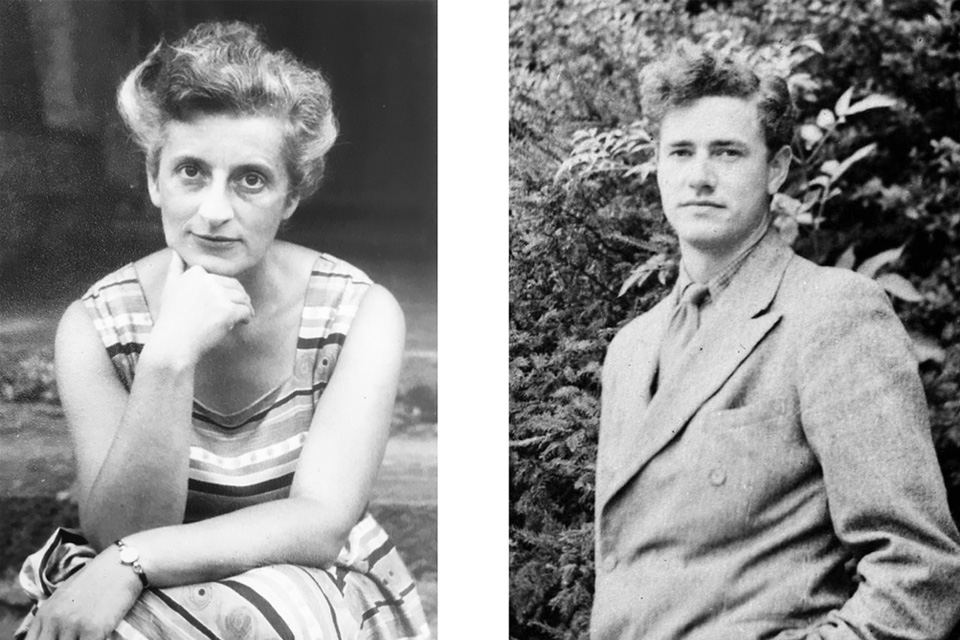

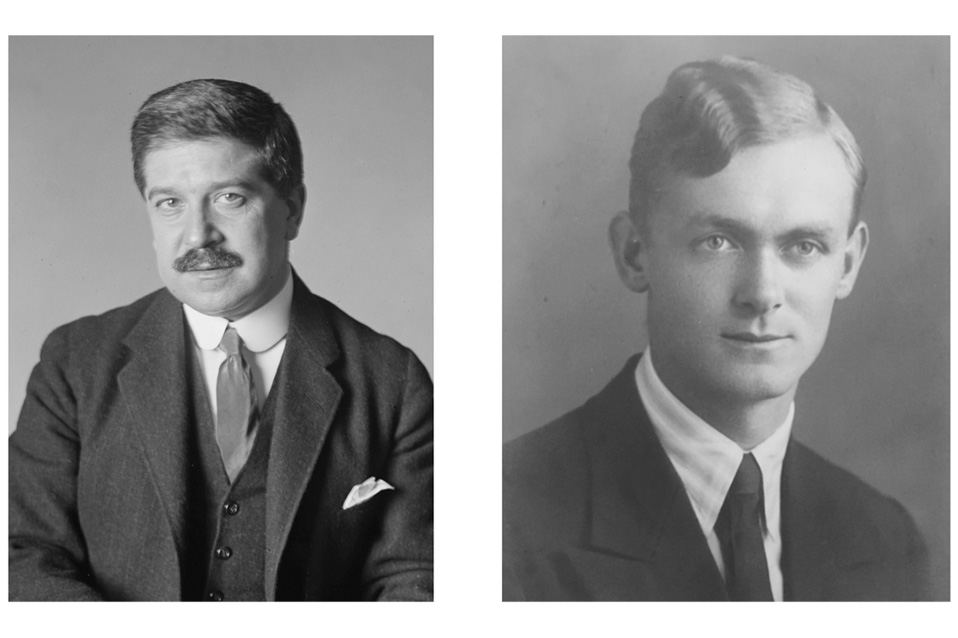

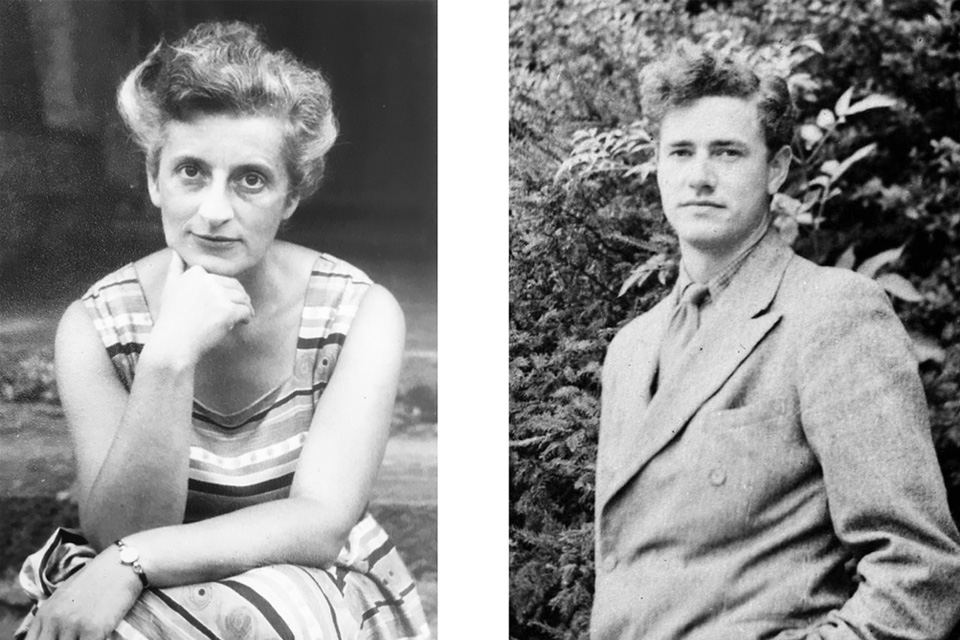

The original idea for the Summer School came from the Austrian émigré pianist Artur Schnabel (below left), while he was performing in 1947 at the first Edinburgh Festival (itself founded by another Austrian émigré, Rudolf Bing). It was also Schnabel’s suggestion that the Summer School should be directed by his former pupil, William Glock (pictured below right around the time of his studies with Schnabel as a young man). This turned out to be a hugely significant decision for music in Britain, as Glock went on to become Controller of Music at the BBC a decade later, and the musical ideas and connections first forged at the Summer School played out on a national stage.

Left: Artur Schnabel, photographer unknown (Wikimedia Commons)

Right: William Glock as a young man, photographer unknown (William Glock Archive)

William Glock's time in Berlin, studying with Schnabel from 1930 to 1933, was profoundly important to him — all the more so since he had to overcome some opposition to get there. He never forgot the two eminent composers at the RCM who insisted to him (during his unsuccessful interview for a bursary to fund his studies with Schnabel) that there was ‘no need whatever to look abroad for a teacher’. It was, he remembered, ‘the first of many examples of insularity that I was to meet during the course of my career’. Years later, when planning the first Summer School, Glock was determined to include great musicians from all over the world — a decision which brought more criticism from some in the British conservatoires. ‘But such blinkered opposition only spurred me on all the more,’ said Glock. ‘What mattered was that many young musicians found themselves confronted with standards they had never known before, and which remained an example ever afterwards.’ [2]

Berlin in 1930 was one of the great musical centres of the world, and the young Glock was overwhelmed by musical experiences the like of which he had never dreamed: Wilhelm Furtwängler conducting the Berlin Philharmonic, Otto Klemperer at the Kroll Opera and Erich Kleiber at the Staatsoper Unter den Linden, the Busch and Rosé Quartets, the latest music from Hindemith and Stravinsky, and above all the classes and intimate music-making sessions at Schnabel’s home. Schnabel was, for Glock, ‘the ONLY pianist in the world,’ and ‘when he plays in a ROOM, he is ten times better than in a concert hall.’ [3] The picture below shows Schnabel playing chamber music in Berlin at that time, with Bronisław Huberman, Pablo Casals and Paul Hindemith — four of the greatest musicians in Europe making music together, not long before all four were displaced by fascism.

Bronisław Huberman, Pablo Casals, Artur Schnabel and Paul Hindemith, Berlin 1933, photographer unknown (Wikimedia Commons)

The terrible destruction that followed would undoubtedly have strengthened Glock’s memories of a wonderful musical world now lost. The next time he saw Berlin (in 1947) the ruins were such that he could no longer find his way around the city he had once known so well.

Brandenburg Gate, Berlin 1945, photograph by Carl Weinrother (Bundesarchiv via Wikimedia Commons)

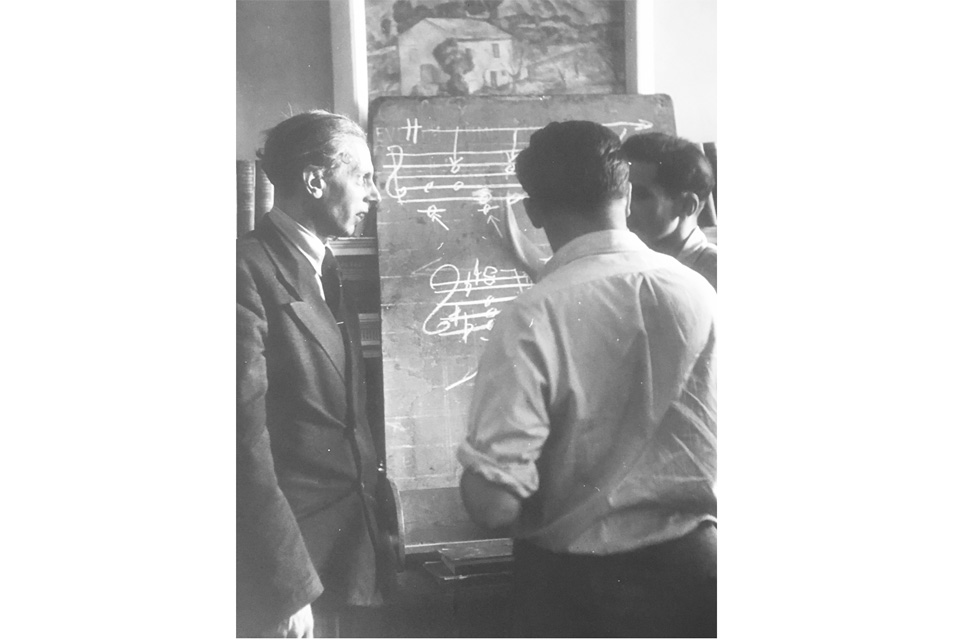

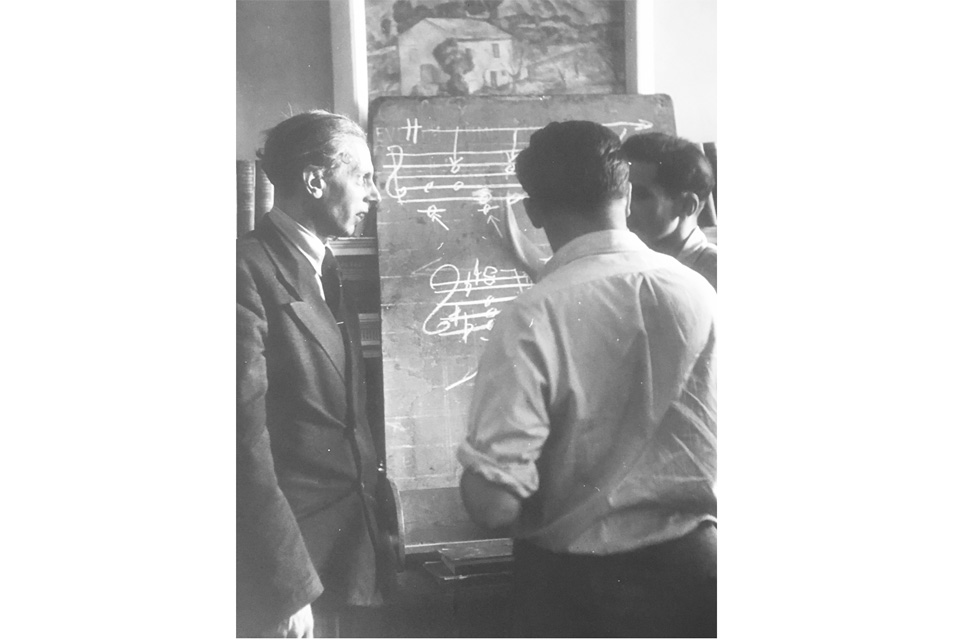

Glock’s trip back to Berlin in 1947 was part of a tour of occupied Europe that he undertook on behalf of the new Third Programme of the BBC, which had started broadcasting in the autumn of 1946. His mission was to find out what had been going on musically in Europe since 1939, to aid the BBC’s attempts to bring to postwar listeners ‘the best that has been thought, or said, or composed in all the world,’ in the words of the BBC Director-General William Haley. The invitation to run the new Summer School of Music suggested by Schnabel came just after Glock returned from this tour, so the knowledge and contacts he had gained enriched the Summer School as well as the BBC. For example, the composer Boris Blacher, with whom Glock said he had spent ‘my most rewarding hours in Berlin’ during his 1947 trip, taught at the Summer School in both 1949 and 1950 (the picture below was taken during one of his classes there) — and he made such an impression on young British composers that at least one (Francis Burt) followed him back to Berlin.

Boris Blacher, Bryanston 1949, photographer unknown (Dartington Summer School Foundation)

Another of Glock’s Berlin contacts who taught composition at the Summer School was Paul Hindemith, whom Glock first encountered though his composition classes at the Berliner Hochschule in the 1930s. Hindemith came to Bryanston in 1948, and teaching composition alongside him in that opening year was Nadia Boulanger — it is a sign of the compelling nature of Glock’s vision, and the respect which his musical judgement commanded, that two of the greatest composition teachers in the world would come and take part in a new venture in provincial England. As Boulanger wrote to Glock on receiving his invitation, ‘the way you approach music and thinking seems to me so right, that I shall of course come.’ [4]

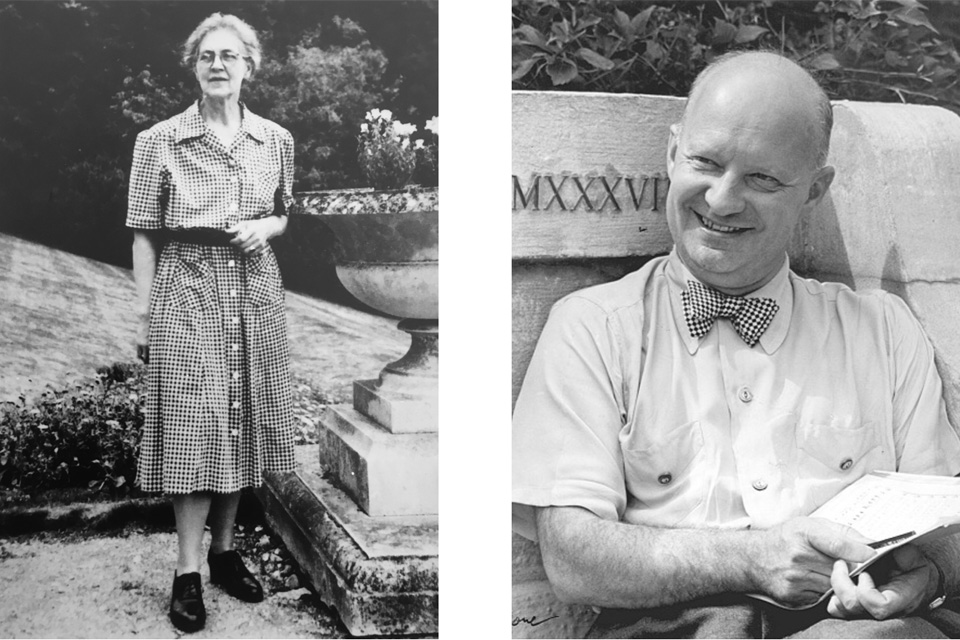

Left: Nadia Boulanger, Bryanston 1948, photographer unknown (Dartington Summer School Foundation)

Right: Paul Hindemith, photographer unknown (Wikimedia Commons)

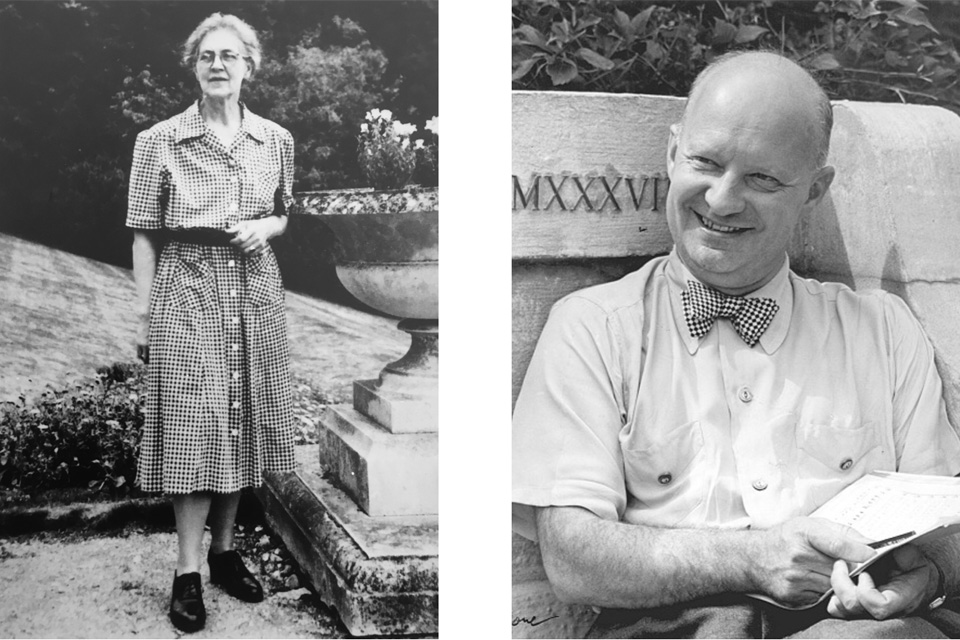

Artur Schnabel’s presence at the first Summer School helped draw many other excellent pianists to teach and perform there, including more of his former pupils, as well as his son Karl-Ulrich Schnabel, who gave several recitals in the opening year, with his wife, the American pianist Helen Vogel. Pictured below are two Schnabel pupils who were to become regulars at the Summer School: Maria Donska (originally from Poland she had studied with Schnabel in Berlin in the 1920s, before coming to London after the Nazis took power) and Noel Mewton-Wood (originally from Australia, he had studied with Schnabel in Italy in the mid-1930s after Schnabel was forced to leave Berlin). The pianists at the Summer School in its first year also included Monique Haas, Paul Baumgartner and Dame Myra Hess, particularly famous at that time for her remarkable wartime concert series at the National Gallery.

Left: Maria Donska, photograph by Catharine Scudamore (Dartington Summer School Foundation)

Right: Noel Mewton-Wood, photograph by Catharine Scudamore (Dartington Summer School Foundation)

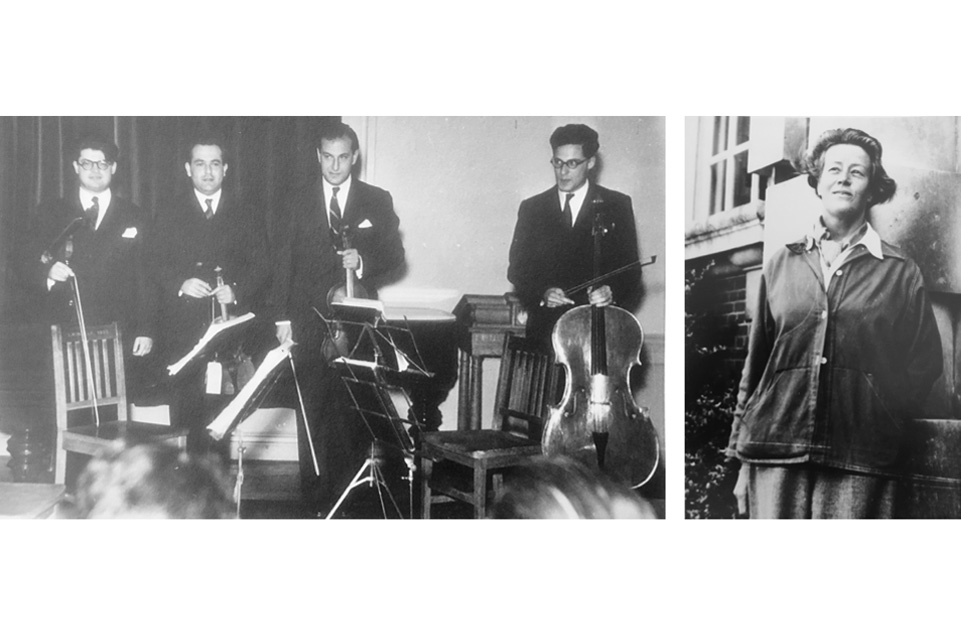

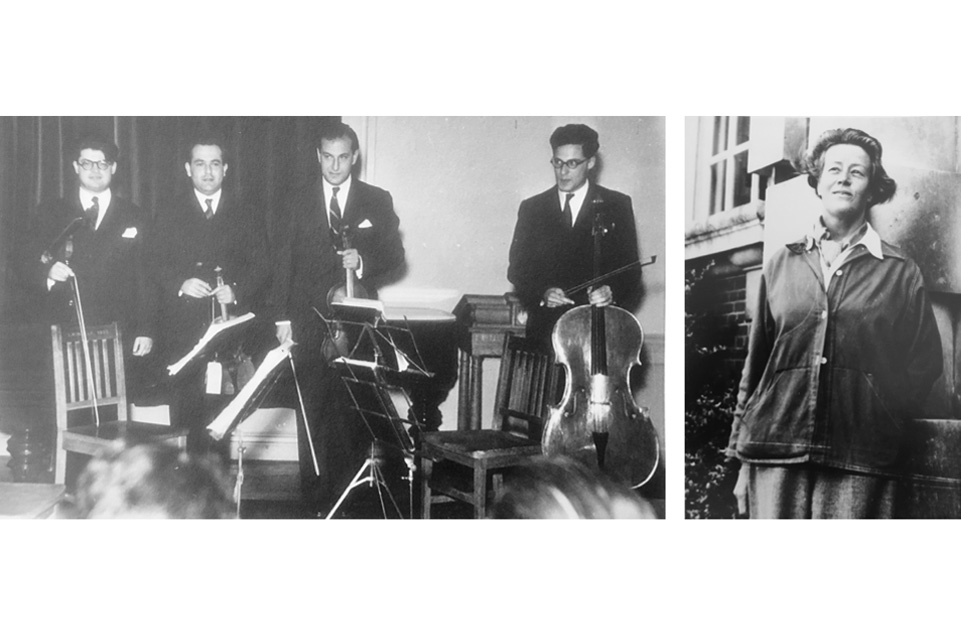

Chamber music in that first year was dominated by the newly-formed Amadeus Quartet, who were to be Summer School regulars for many years. The photograph below was taken at a recital in their second year there, 1949, possibly after their performance of the First String Quartet by Priaulx Rainier (below right), the South African-born composer who was teaching the student chamber music groups at the Summer School. She met the Amadeus Quartet at the first Summer School in 1948, and they recorded the work for Decca shortly afterwards — their first commercial record release.

Left: Amadeus String Quartet, Bryanston 1949, photographer unknown (Dartington Summer School Foundation)

Right: Priaulx Rainier, photograph by Catharine Scudamore (Dartington Summer School Foundation)

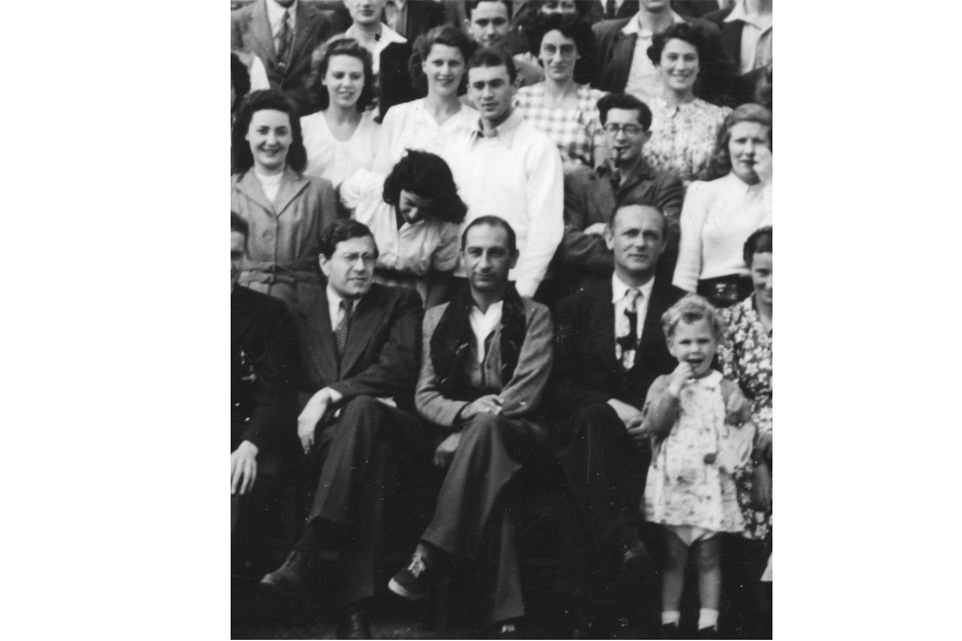

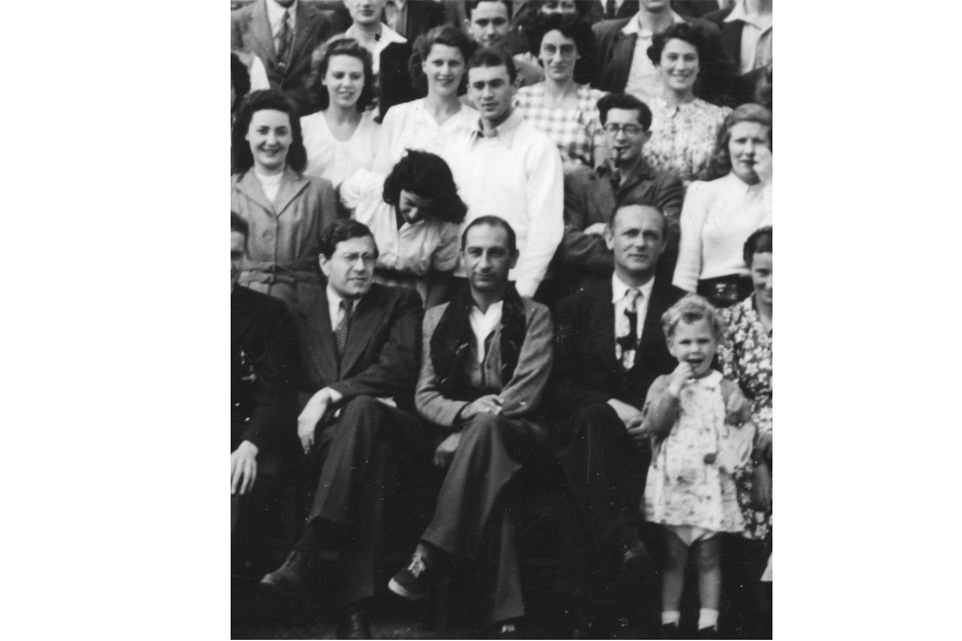

Other new music played by the Amadeus in the early years of the Summer School included Mátyás Seiber’s Third Quartet (Quartetto lirico) and Michael Tippett’s Second Quartet. The Amadeus also encountered another kind of ‘new’ music at the Summer School, when they were asked to play Peter Warlock’s arrangements of seventeenth-century English viol music, alongside lectures by the Oxford Professor of Music J.A. Westrup and vocal music sung by the pioneer of historically-informed performance, counter-tenor Alfred Deller. The Summer School was remarkable for the amount and range of early music performed and taught there from its earliest years — and this repertoire was noticeably dominated by English musicians at first. As well as Deller and Westrup, Henry Washington and the Brompton Oratory Choir performed sixteenth-century choral music, Anthony Bernard and the London Chamber Singers presented music from the fifteenth-century Burgundian court, Anthony Milner directed a series of concerts of medieval music, the Cambridge University madrigal singers under Boris Ord made regular appearances, and Dom Aldhelm Dean OSB taught the singing of plainchant. In 1948 Glock did invite the Austrian émigré composer and academic Egon Wellesz (now teaching at Oxford) to lecture on Byzantine music, but in the event Wellesz was unable to come. The German émigré conductor Walter Goehr, who had recently given the first modern British performance of the Monteverdi Vespers, came to conduct and lecture at the Summer School in 1948, but his varied programmes there concentrated on later music, including an illustrated lecture and three performances of Bartók’s Divertimento for Strings, the last work Bartók composed before he left Hungary for America. (The photograph below shows Goehr with students and colleagues at the first Summer School, seated between Karl-Ulrich Schnabel and William Glock.)

Karl-Ulrich Schnabel, Walter Goehr and William Glock with Summer School participants, Bryanston 1948 (Dartington Summer School Foundation)

The Amadeus took part in pre-classical music only in their first year, and though they continued to explore some twentieth-century music (Peter Racine Fricker’s Second Quartet, Bartók’s Fourth, Hindemith’s Sixth, Stravinsky’s Three Pieces and the Shostakovich Piano Quintet with William Glock at the piano), they generally concentrated on the Viennese classics. The music of Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven and Schubert was in any case at the core of the Summer School’s varied repertoire — a place where all these diverse musicians could meet. It was also close to William Glock’s own heart, being the music he tended to play himself. Even in this canonic repertoire there was much still unknown to most British listeners and players, and Glock was determined to explore it all. He played countless piano trios, quartets and quintets with the Amadeus and others, and he also accompanied visiting lieder singers like the great Elisabeth Schumann in 1950 and 1951 and a young Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau in 1953 and 1955. The pictures below show Schumann and Fischer-Dieskau on their respective first visits to the Summer School, and William Glock with the American Juilliard Quartet in 1955.

Left: Elisabeth Schumann, Bryanston 1950, photograph by Catharine Scudamore (Dartington Summer School Foundation)

Right: Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, Dartington 1953, photograph by Catharine Scudamore (Dartington Summer School Foundation)

William Glock with the Juilliard String Quartet, Dartington 1955, photograph by Catharine Scudamore (Dartington Summer School Foundation)

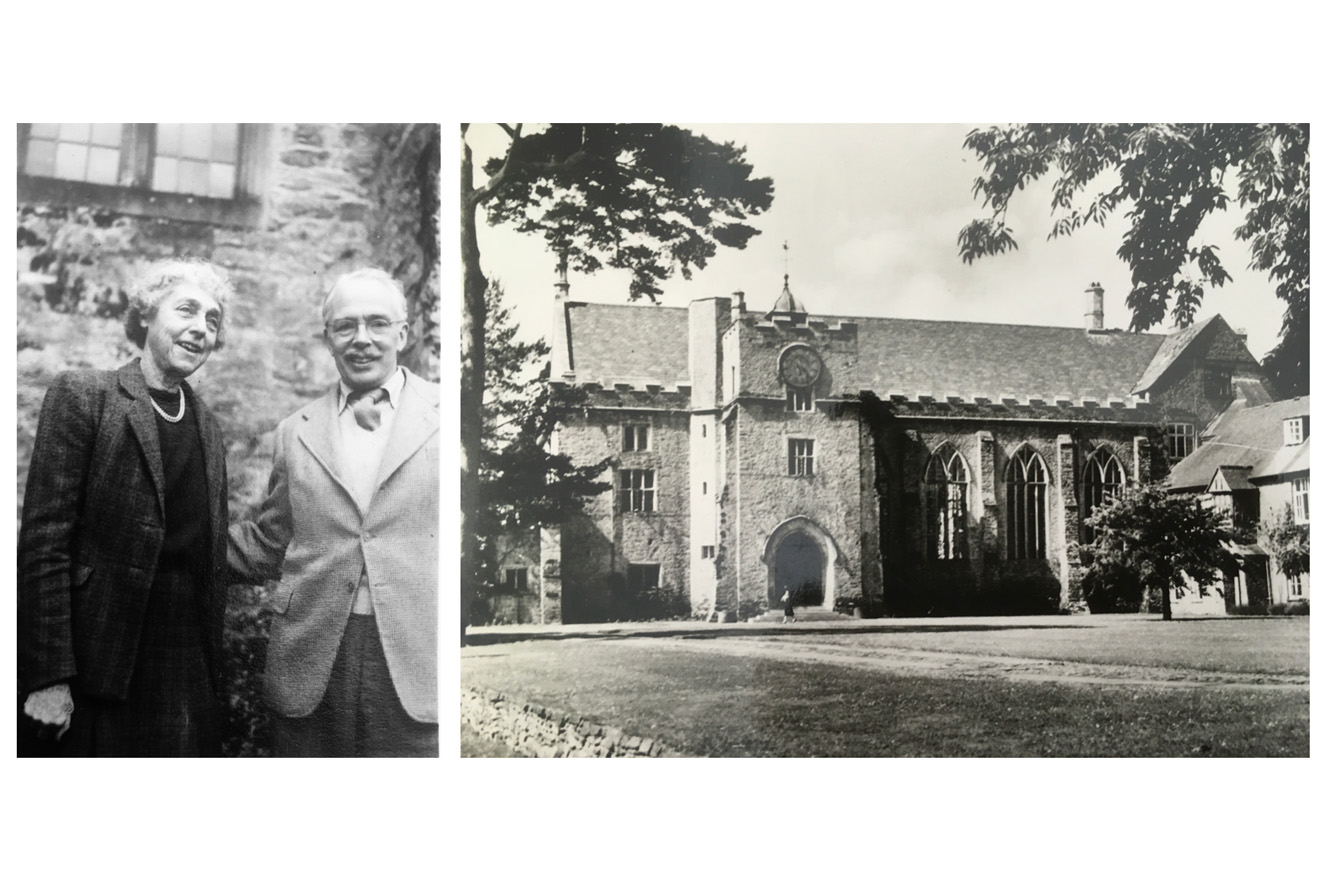

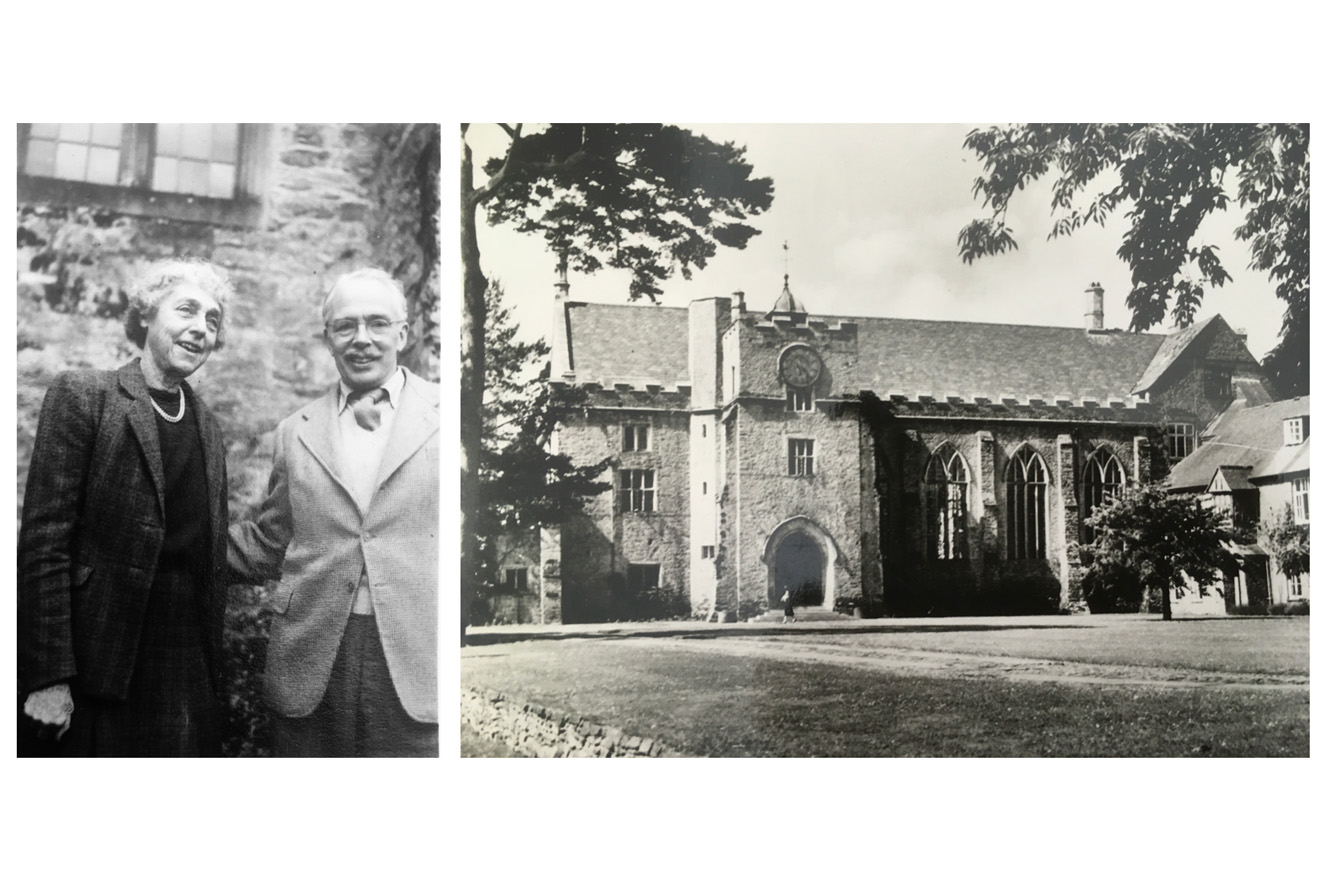

In 1951 William Glock was invited to lecture at Dartington Hall in Devon for the first time — and as a result fell ‘under the spell of its idyllic surroundings and the splendour and history of its fourteenth-century courtyard and Hall.’[5] The following year agreement was reached with the Elmhirsts and their trustees that the Summer School should leave Bryanston School and be hosted by Dartington from the summer of 1953.

Left: Dorothy and Leonard Elmhirst, Dartington 1953, photograph by Catharine Scudamore (Dartington Summer School Foundation)

Right: Dartington Hall, photographer unknown (Dartington Summer School)

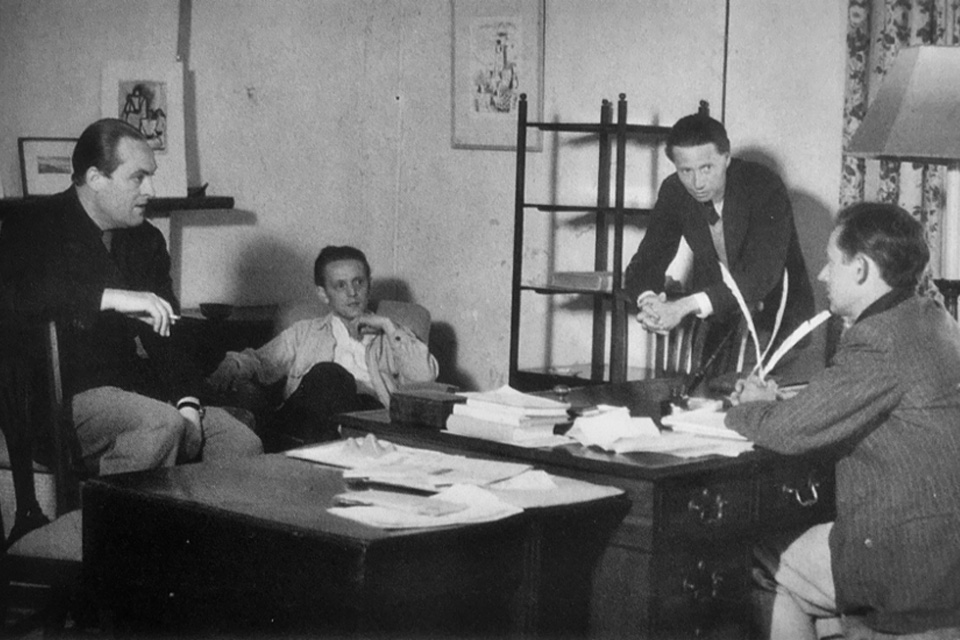

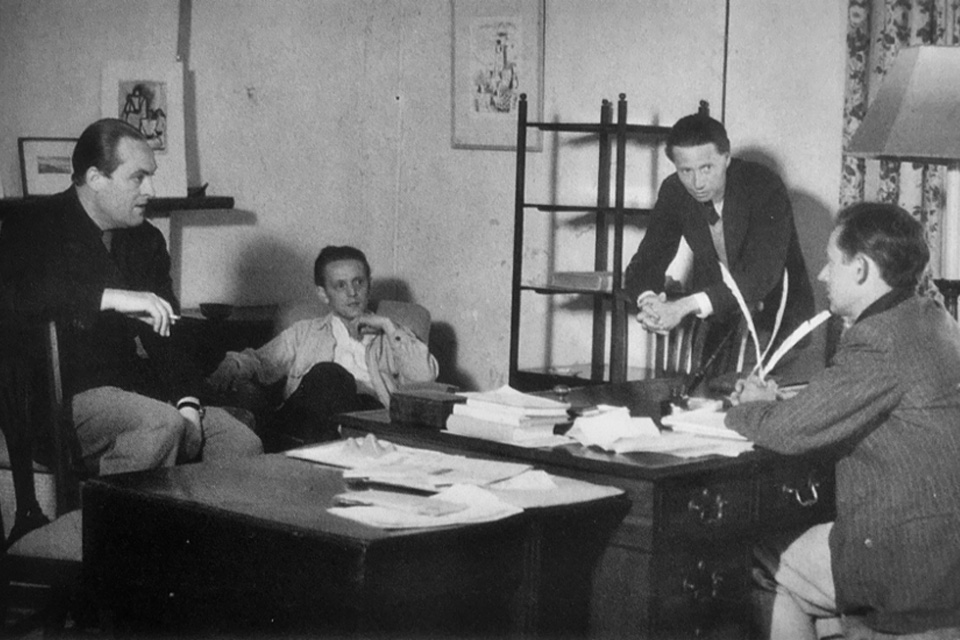

Dartington Hall and the surrounding estate had been bought by Dorothy and Leonard Elmhirst in 1925 and they quickly restored its ancient buildings and transformed it into an extraordinary centre of rural regeneration, progressive education and artistic excellence. In the 1930s it became a place of refuge for many renowned Continental artists fleeing from the Nazis, including the whole of the Ballets Jooss and the Jooss-Leeder Ballet School, who transferred to Dartington together with Michael Chekhov’s Theatre School. They were joined by the great pioneer of modern dance Rudolf von Laban, the artist and designer Hein Heckroth, and the architect and Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius, who worked on the conversion of Dartington’s Barn Theatre. Hans Oppenheim also came to direct the Dartington Hall Music Group after a time as Fritz Busch’s assistant conductor at Glyndebourne. The photograph below shows Hein Heckroth, Sigurd Leeder and Hans Oppenheim with the Dartington Arts Administrator Christopher Martin in his office in the 1930s.

Hein Heckroth, Sigurd Leeder, Hans Oppenheim and Christopher Martin, Dartington 1930s, photographer unknown (Dartington Trust)

The 1930s international artistic community of refugees at Dartington was broken up by the outbreak of war in 1939, which brought internment to ‘enemy aliens’ and a different kind of migrant for Dartington to welcome, including child evacuees and — particularly important for music — the composer and educator Imogen Holst.

Holst arrived at Dartington in 1942, in a state of some exhaustion due to her wartime work as a ‘music traveller’ (another kind of mobility) for the Council for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts (CEMA) — the forerunner of what was to become the Arts Council after the war. Holst had been assigned the entire west of England (from Oxfordshire to the Scilly Isles) as her area of responsibility, where she travelled from village to village supporting and organising local music-making. After two and a half years of this punishing schedule, she arrived at Dartington, which the Elmhirsts invited her to make her home while she worked around Devon and Cornwall. Before long she had resigned her CEMA post and accepted their invitation to work instead at Dartington, first on a major report into English musical life that was underway there and then setting up new training courses for music teachers.

Left: Imogen Holst, Bryanston 1950, photograph by Catharine Scudamore (Dartington Summer School Foundation)

Right: Imogen Holst conducting at Dartington Hall, photographer unknown (Dartington Summer School Foundation)

Holst was an inspirational teacher, who could range from amateur and community music-making to the highest of professional standards. In 1948 she was a key part of Glock’s new Summer School at Bryanston (where she is pictured above left) — and was central to its mission to bridge the amateur-professional divide, educating the audience alongside performers and composers. At the Summer School she ran courses for music teachers, led orchestral and choral groups (the photograph above right shows her conducting in Dartington’s Great Hall), and gave a hugely successful series of accessible lectures on the fundamentals of music. In these lectures, she ‘touched on profundities in a form of such simplicity’, remembered the pianist Joyce Rathbone, who recalled the wonderful scene of ‘Nadia Boulanger and Hindemith sitting side by side in the front row … each holding an improvised percussion instrument consisting of a handkerchief containing coins, with which they performed in response to Imogen’s instructions, gazing up at her with the concentrated attention of two young children.’ [6]

Holst was also responsible for bringing the Amadeus Quartet to the first Summer School, having been instrumental in their formation as a quartet, only a few months before. She had first met the 22-year-old Norbert Brainin through Hans Oppenheim in 1945, after which she invited him down to Dartington and encouraged his ambition to start a new string quartet with two fellow-Viennese émigrés he had met in the wartime internment camps, and a young English cellist they had discovered though Max Rostal, their teacher. In 1947 Holst arranged for all four to be invited to Dartington to spend time in rehearsal and study together, and the results were remarkable. The ‘Brainin Quartet’ gave their first concert together in Dartington Hall on 13 July 1947, after which Dorothy Elmhirst bought Brainin a Guarneri violin and in January 1948 Holst sponsored their Wigmore Hall debut under the new name they would shortly make famous.

Amadeus String Quartet on the lawn at Dartington, photograph by Catharine Scudamore (Dartington Summer School Foundation)

Their arrival at the Summer School a few months later, and their regular return each summer as their career took off, must have been an important part of the Amadeus’ musical development. Performing and coaching and building their repertoire alongside so many great musicians was a unique opportunity, not to mention the restorative effects for busy young professionals of the holiday atmosphere of the Summer School, especially once it arrived in the comfortable surroundings of Dartington. The photograph below records their encounter with the great Romanian violinist, composer and conductor George Enescu, whom Glock described as ‘the greatest instrumental teacher the Summer School ever had.’ Enescu taught and performed at the Summer School in 1949, 1950 and 1952, and Glock recalled listening to him spend an afternoon taking the Amadeus through the tempos of each movement of the Beethoven quartets. ‘Little was said, but from his seat at the piano he managed in a few gestures to communicate not only the tempos but also the essence of each movement. He knew everything from memory.’

George Enescu and the Amadeus String Quartet at Bryanston, photograph by George Konig (Dartington Summer School Foundation)

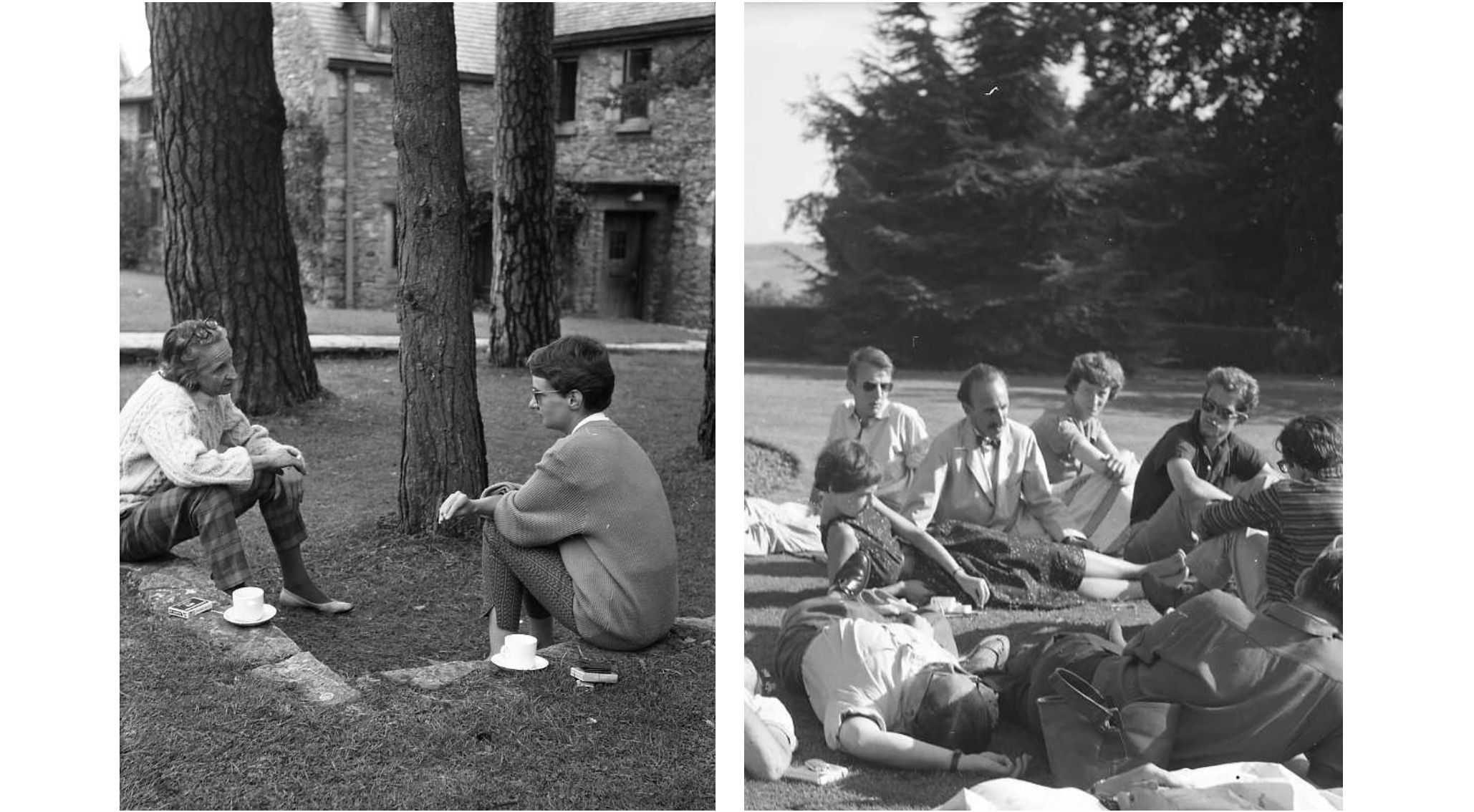

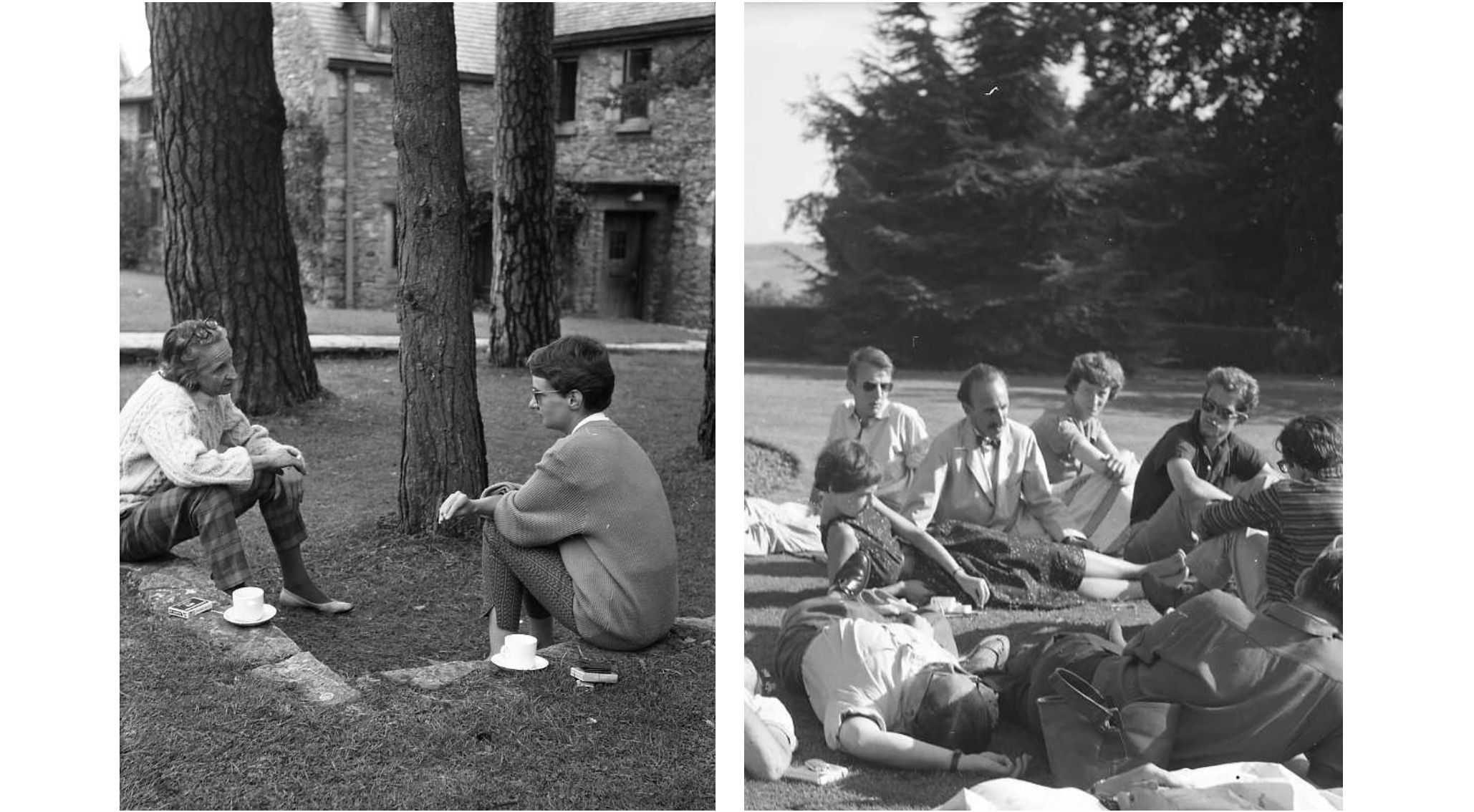

‘The Summer School provided an atmosphere in which the learning process seemed to take place often by leaps and bounds,’ remembered Susan Bradshaw, describing the unique feeling she had that ‘everybody there was learning and absorbing ideas from everybody else, regardless of age or professional status.’ [8]The photographs below show Bradshaw at Dartington in conversation with the English composer Elizabeth Lutyens (left), and (right) with Richard Rodney Bennett, Thea Musgrave, Cornelius Cardew and others listening to the Viennese émigré writer Hans Keller.

Left: Elisabeth Lutyens and Susan Bradshaw, photograph by Catharine Scudamore (Dartington Summer School Foundation)

Right: 25. Hans Keller with Summer School participants, including Susan Bradshaw, Richard Rodney Bennett, Thea Musgrave and Cornelius Cardew, Dartington 1960, photograph by Catharine Scudamore (Dartington Summer School Foundation)

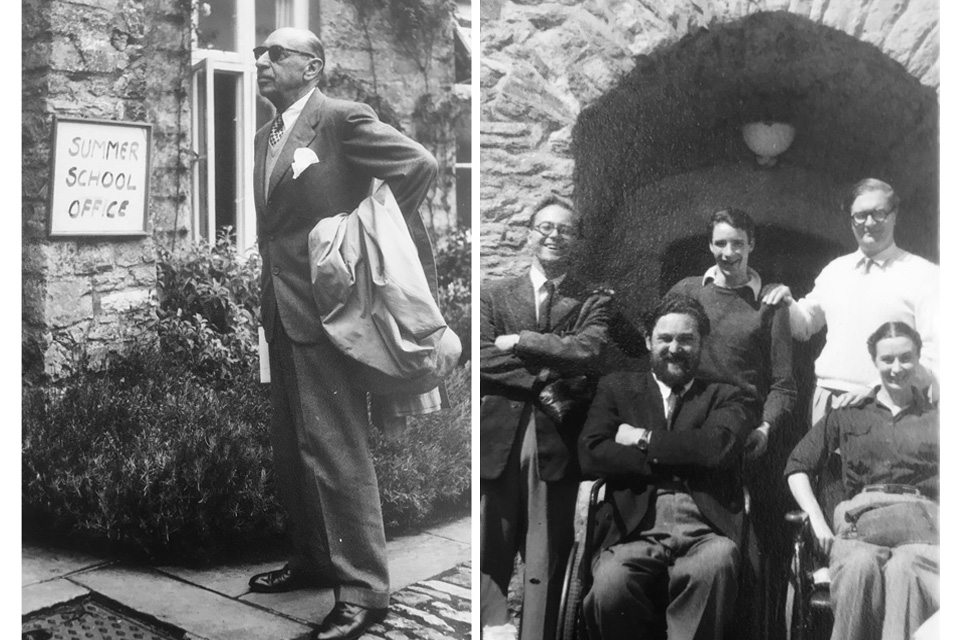

Keller first came to the Summer School in 1958. He was well known by then as a stimulating and provocative thinker and writer, who had caused a stir the previous year with the first of a series of innovative radio programmes analysing music in sound alone: ‘The Unity of Contrasting Themes’. Glock was fascinated: he published the score of Keller’s first analysis in his journal The Score and invited Keller to Dartington to give classes and present his wordless analytical method. Glock commissioned Keller to write a new analytical score of Haydn’s ‘Lark’ Quartet for the 1958 Summer School, and persuaded the string teachers at the Dartington Arts Centre to form a string quartet to play it. The Dartington String Quartet (pictured below with Keller), thus became one of several professional ensembles formed at the Summer School, and the first of many British string quartets coached there by Keller, whose work at Dartington and later at the BBC revitalised chamber music in Britain.

Hans Keller and the Dartington String Quartet, Dartington 1960, photograph by Catharine Scudamore (Dartington Summer School Foundation)

At the Summer School, Keller's magnetic personality and fascinating ideas were a hit with students: ‘People came alive in his presence,’ remembered Bradshaw; ‘He took every encounter, every question, as if it were the most important issue of the moment and would talk all day — even into the early hours of the next morning — in order to resolve it. He was the only person I ever met to whom everything (particularly, of course, musical things) really mattered.’ [9] Keller took a characteristically intense interest in everything going on at the Summer School and immediately started planning what he would do there the following year. He continued to teach at Dartington every summer until his death. ‘He taught a whole generation of us,’ wrote the composer Hugh Wood (who had been coming to Dartington since 1948 and regarded it as the most important part of his musical education); ‘Only a lucky few of us formally, the rest by this process of friendly undogmatic osmosis of a remarkable personality into one’s own.’ [10]

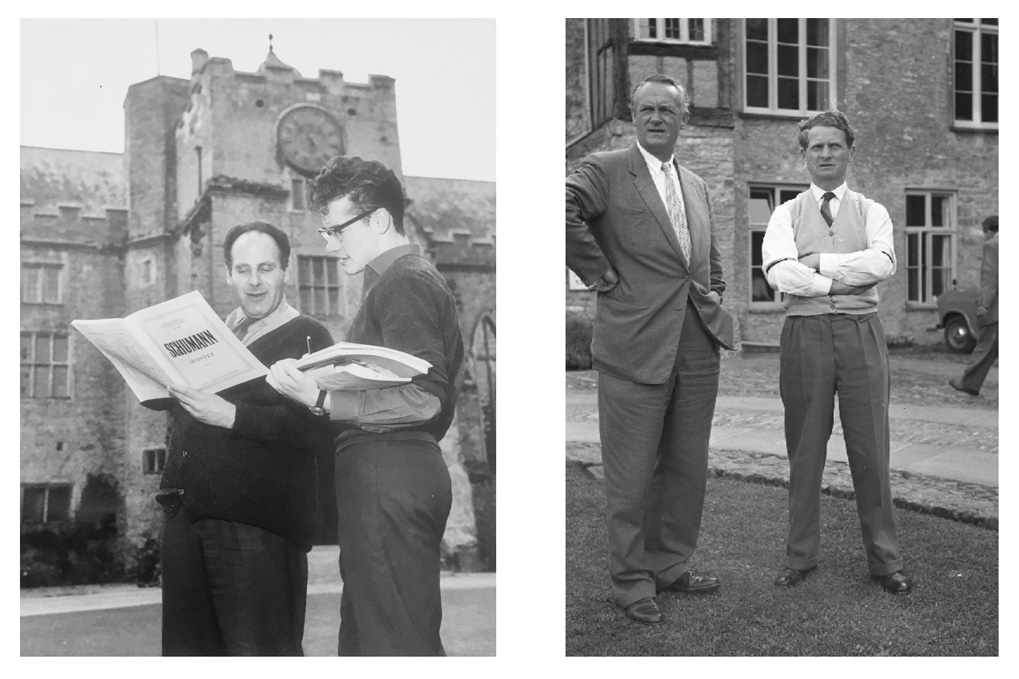

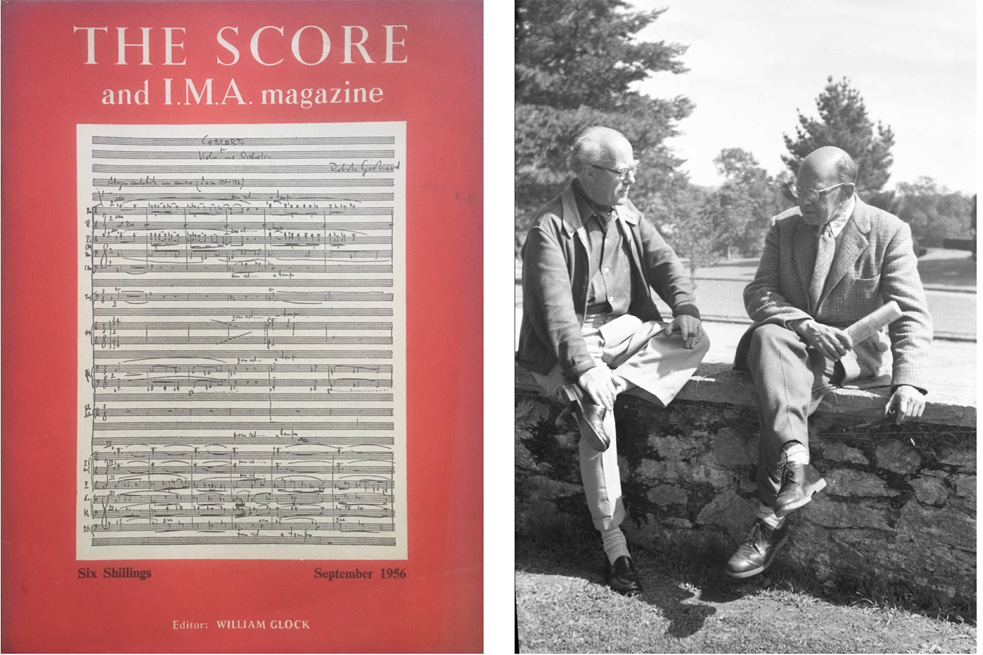

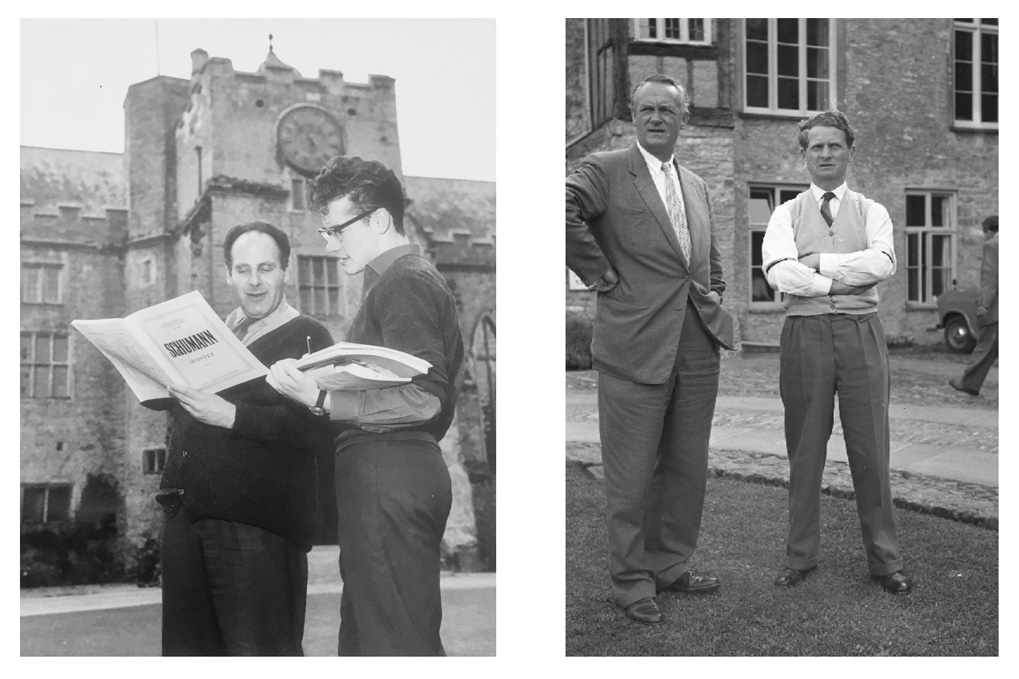

Left: William Glock and Peter Gellhorn, photograph by Catharine Scudamore (Dartington Summer School Foundation)

Right: Paul Hamburger and student, photograph by Catharine Scudamore (Dartington Summer School Foundation)

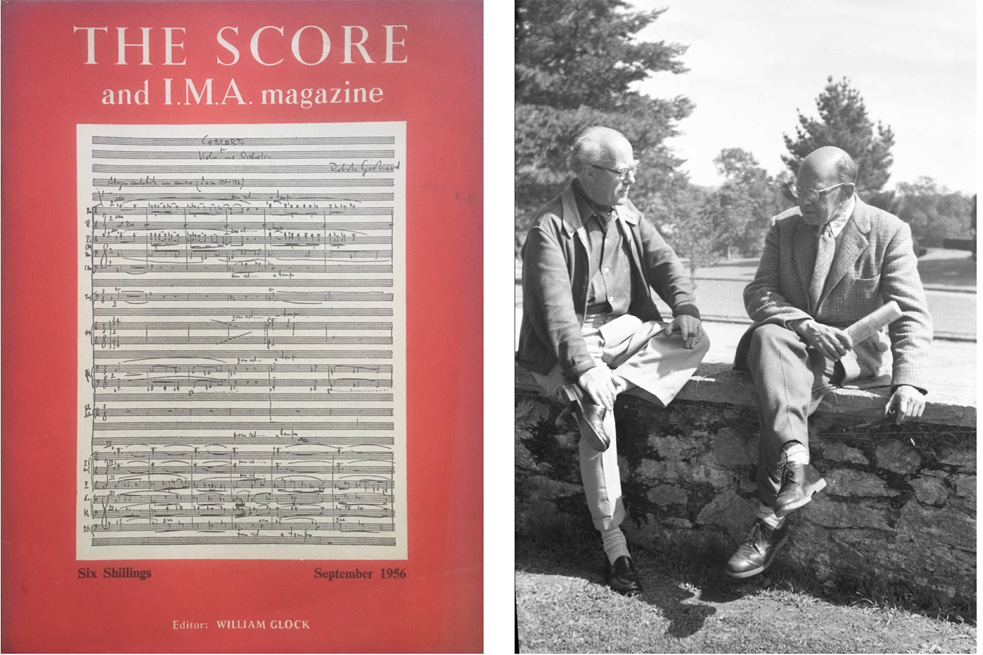

When William Glock became Controller of the BBC’s Music Division in 1959, Keller was the first of the wave of new staff who followed him to the BBC. Many of these new faces were, like Keller, already involved with the Summer School. Also like Keller, several were central European émigrés, including the pianist Paul Hamburger (above left, teaching at Dartington), who became the BBC’s principal accompanist and later Chief Producer (Artists), and the conductor Peter Gellhorn (above right at Dartington with William Glock), who directed the BBC Singers. Already involved with the BBC before Glock arrived there were two more émigré conductors who had also taught at the Summer School: the Berlin-born Walter Goehr, who directed the BBC Theatre Orchestra (among much else), and the Viennese-born Rudolf Schwarz, chief conductor of the BBC Symphony Orchestra (he is shown below rehearsing the Summer School orchestra at Dartington in 1954).

Rudolf Schwarz conducting the Summer School Orchestra, Dartington Hall 1955, photograph by Catharine Scudamore (Dartington Summer School Foundation)

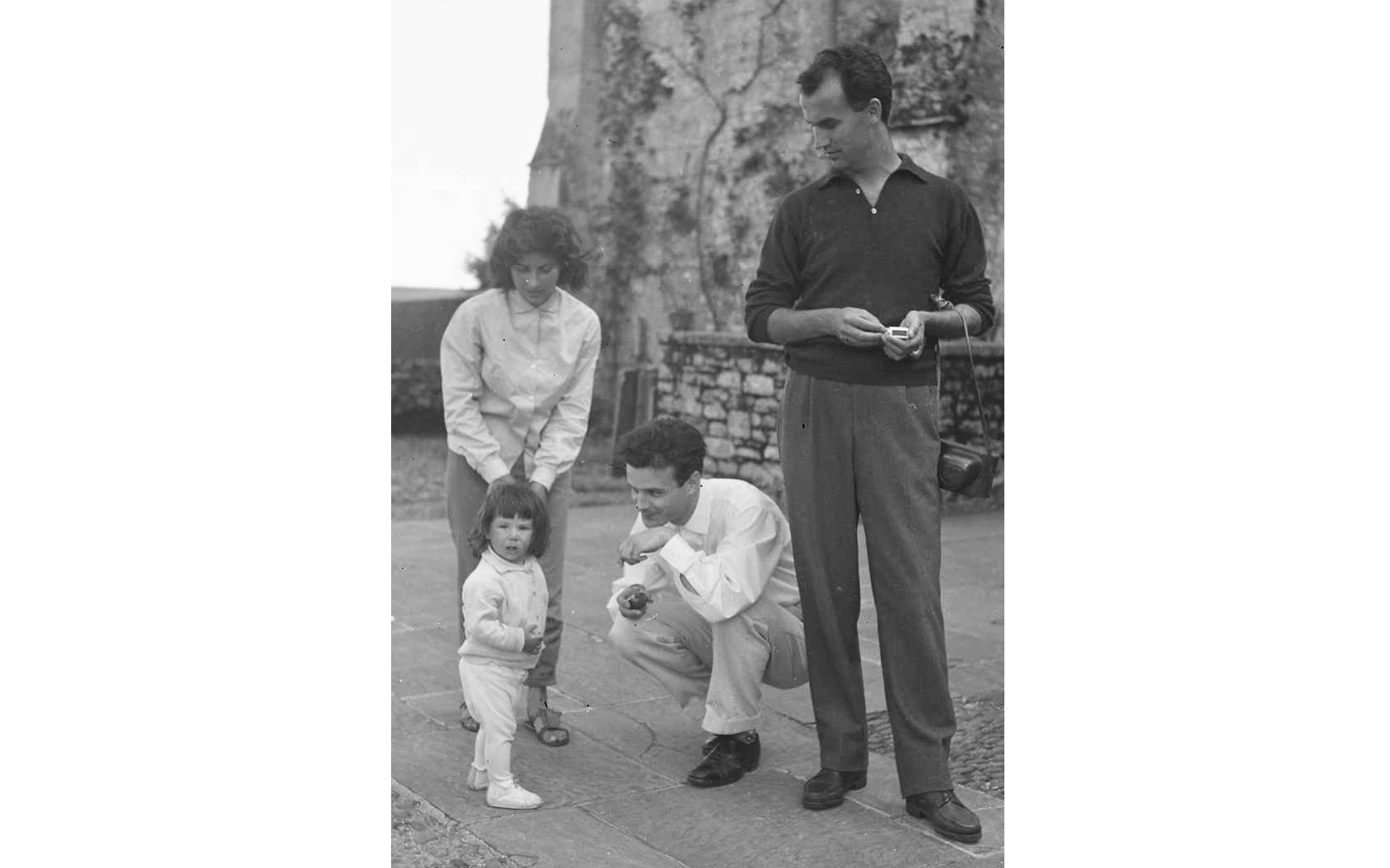

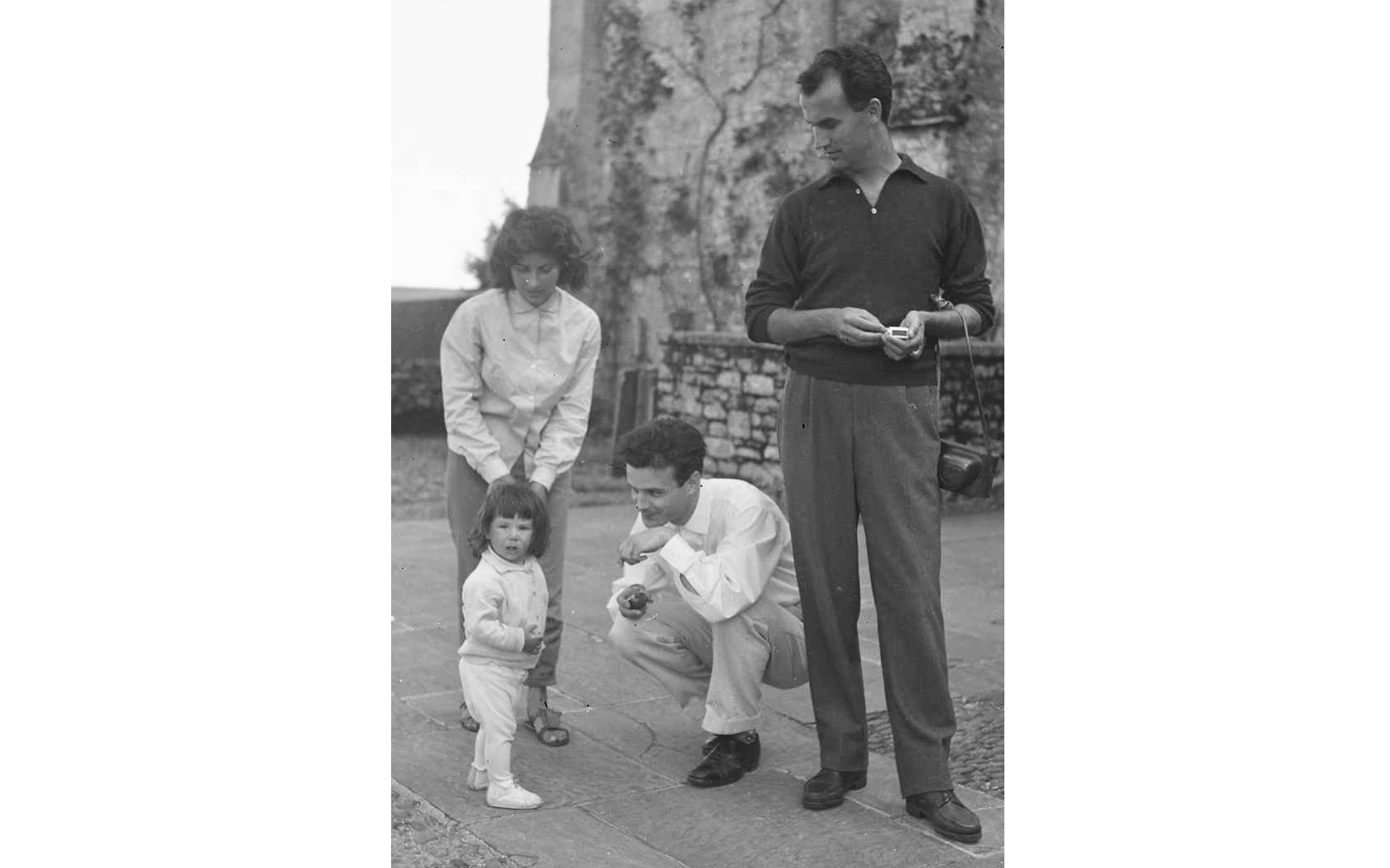

Around the time of the Summer School’s arrival at Dartington in 1953, William Glock became more seriously involved in various international musical organisations and initiatives, which further increased his knowledge of what was happening musically in other countries and his personal contacts with composers and performers there. In 1953 he met the Russian-American composer Nicholas Nabokov, organiser of several grand international musical gatherings; Nabokov invited Glock to the Festival and Congress he was organising in Rome the following year, as a result of which Glock met the Italian composers Luciano Berio, Bruno Maderna, Luigi Nono and Roman Vlad, all of whom then came to teach at Dartington. (Pictured below is Luigi Nono (R), his wife Nuria Schoenberg and their daughter with Peter Maxwell Davies in 1960 — Maxwell Davies was fluent in Italian after his studies in Rome with Petrassi and translated Nono’s lectures for him at Dartington.)

Nuria Schoenberg and Luigi Nono and their daughter with Peter Maxwell Davies, photograph by Catharine Scudamore (Dartington Summer School Foundation)

Also in 1953 Glock joined the music committee of the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in London, becoming its chairman in 1954. The ICA music committee acted as the British section of the International Society for Contemporary Music (ISCM), so from that point on Glock attended all the annual Festivals of the ISCM and ran the ICA’s London concerts. As a result, the Dartington Summer School began to feature an increasing number UK premieres of new works from abroad: Le Marteau sans Maître, for example, which Glock heard premiered at the 1955 ISCM Festival in Baden-Baden, was one of three of Pierre Boulez’s works given their first British performance at the Summer School. This and many other new works were performed by John Carewe’s New Music Ensemble together the Manchester New Music Group that had grown out of Richard Hall’s composition class at the Royal Manchester College of Music, whose members became students and then teachers at the Summer School (while Hall himself became in 1956 Director of Music at Dartington Hall, the post once occupied by Imogen Holst, who had moved to Aldeburgh to work with Benjamin Britten).

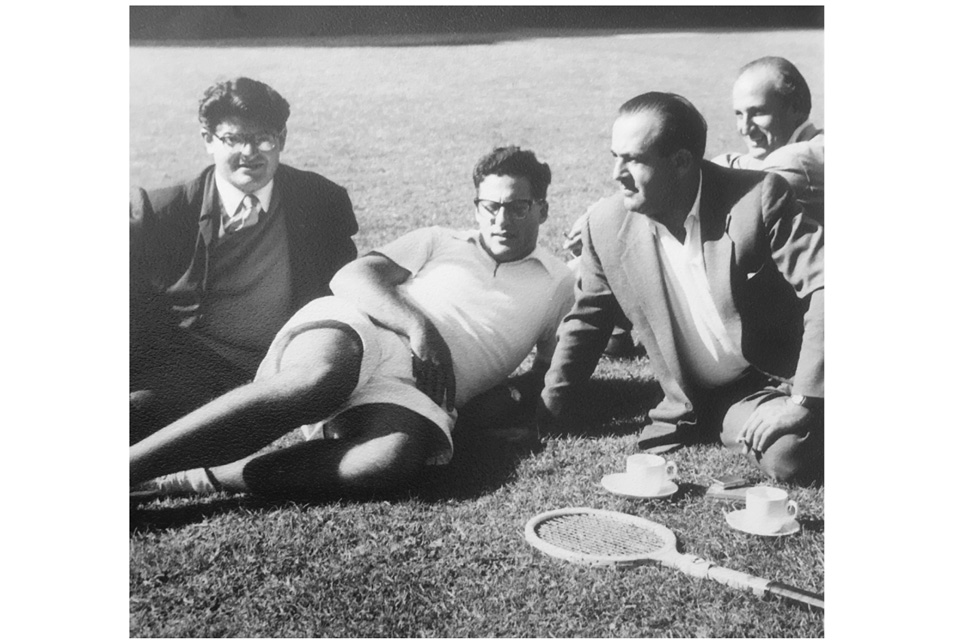

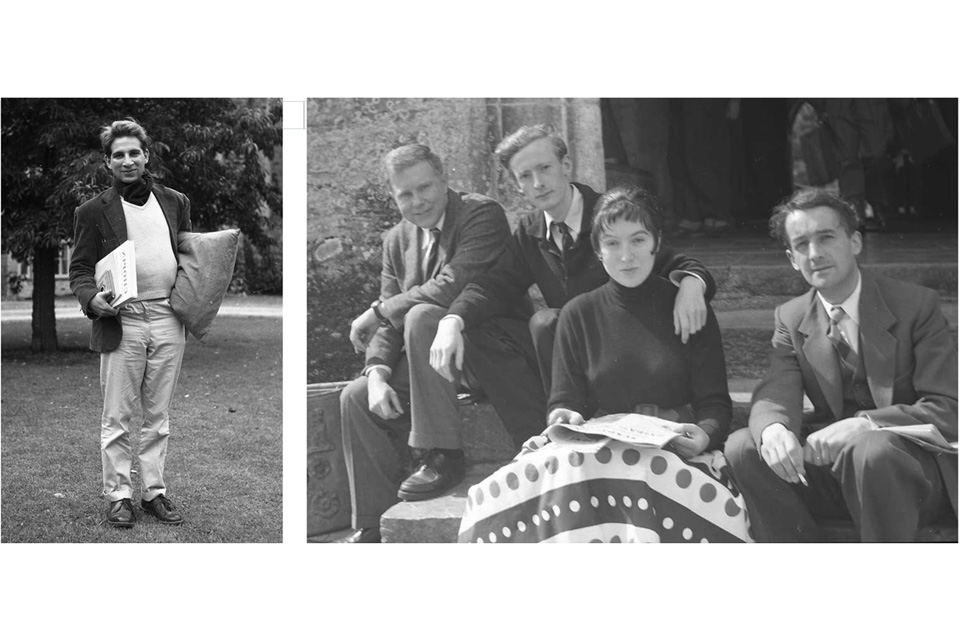

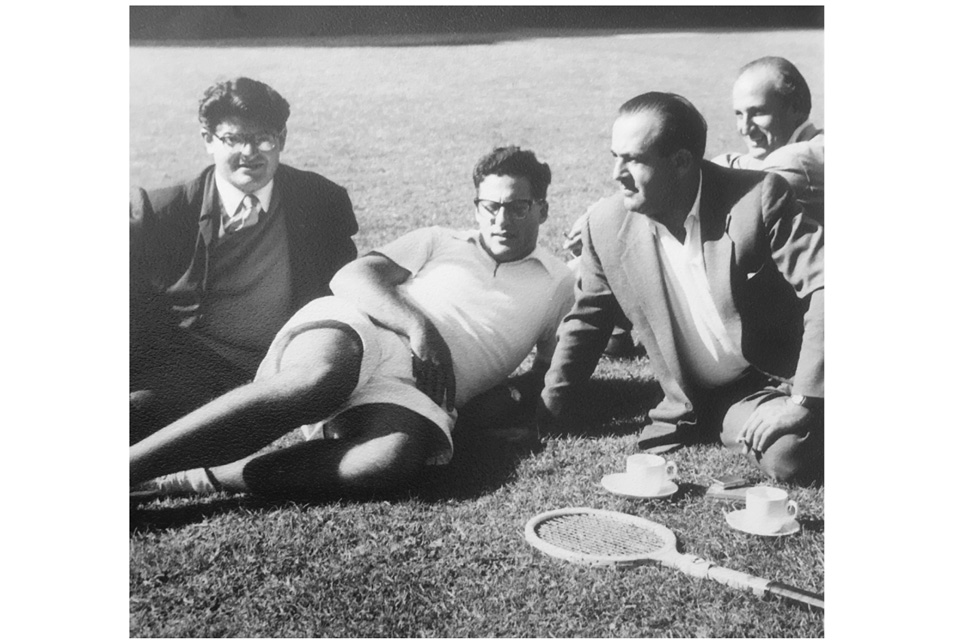

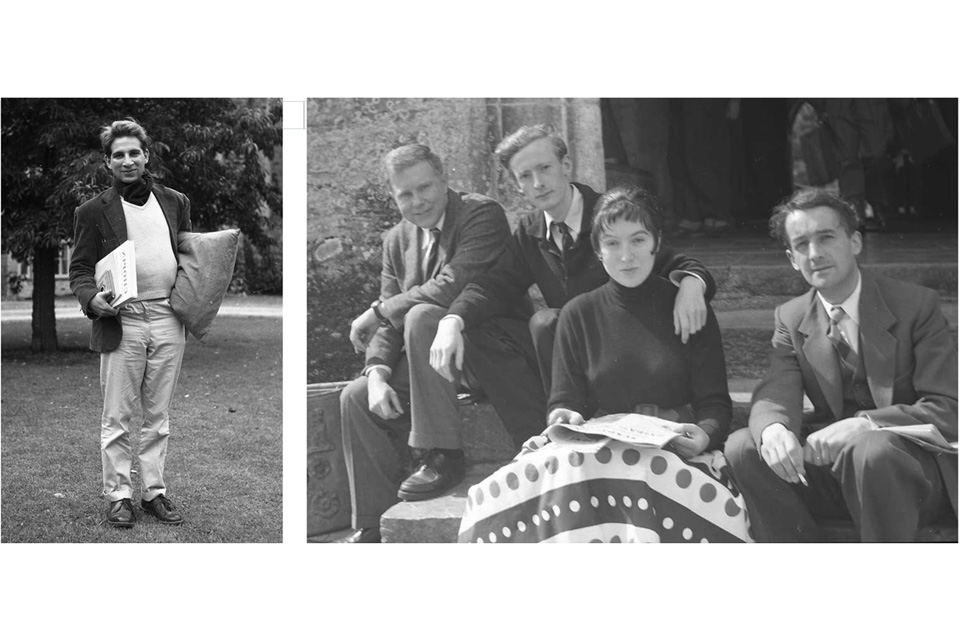

Pictured below left is the 26-year-old Alexander Goehr in 1960, the year he first taught at the Summer School. Below right is the 24-year-old John Carewe (second from left) in 1957, when he and his New Music Ensemble first played at the Summer School, giving the first British performance of Nono’s Polifonica-Monodia-Ritmica and premieres of works by Alexander Goehr, Peter Maxwell Davies, Cornelius Cardew, Susan Bradshaw and Richard Rodney Bennett. Sitting with him in this photograph are the American composer Elliott Carter (whose first two string quartets had their British premieres at Dartington), the Austrian émigré pianist Katharina Wolpe (who gave at Dartington the first British performances of several works by her father, Stefan Wolpe) and the harpsichordist George Malcolm.

Left: Alexander Goehr, Dartington 1960, photograph by Catharine Scudamore (Dartington Summer School Foundation)

Right: Elliott Carter, John Carewe, Katharina Wolpe and George Malcolm, Dartington 1957, photograph by Catharine Scudamore (Dartington Summer School Foundation)

As ever, the combination of new and old music was an important part of Summer School programming, in which premieres of new works could find themselves alongside works written centuries before. For example, George Malcolm premiered Peter Racine Fricker’s 1956 Harpsichord Suite within a programme of works by Gibbons, Bach, Arne and Purcell, while in the same year Hans Oppenheim and the Saltire Singers presented new works by Francis Burt, Bernard Naylor, Iain Hamilton and Benjamin Britten alongside Janequin, Palestrina, Gibbons and Schütz. (‘William, what on earth is all that Bach doing?’ was apparently Luigi Nono’s astonished reaction to this kind of programming.) [11]

An important adjunct to the Summer School’s educative mission right from the very start had been The Score, a new music journal founded and edited by Glock immediately after the conclusion of the first Summer School in 1948. Its first issue (circulated initially among the attenders and supporters of the Summer School) appeared in time for the 1949 Summer School and it continued publishing until the BBC pressured Glock to relinquish the editorship in 1961. It was a kind of cross between Music and Letters (Britain’s chief journal of serious musicology in the interwar period) and the New York journal Modern Music, of which Glock had been an avid reader during the war and which was notable for the high proportion of contributions from composers (rather than critics or scholars). Glock took a similar editorial line in The Score, with the result that the journal became another important link with composers worldwide. Three fifths of its subscribers lived in America (where Modern Music had ceased publication in 1946) and they included Igor Stravinsky, Aaron Copland, Elliott Carter, Virgil Thomson and Roger Sessions, all of whom came to the Summer School — with Sessions apparently declaring it ‘the most stimulating institution of its kind he had attended either side of the Atlantic’. [12]

Left: The Score, September 1956 edition

Right: Roberto Gerhard and Roger Sessions, photograph by Catharine Scudamore (Dartington Summer School Foundation)

The edition of The Score pictured below above is a special volume published in September 1956 in honour of the sixtieth birthday of the Catalan émigré composer Roberto Gerhard (pictured above left at Dartington with Roger Sessions). This was prompted by Glock hearing Gerhard’s First Symphony at the 1955 ISCM Festival in Baden-Baden. At that time, little of Gerhard’s music was published and his works rarely attracted second performances — a situation that Glock was determined to change. The 1956 Summer School featured two world premieres of Gerhard’s music: his String Quartet No.1, played by the Parrenin Quartet, and his Concerto for Strings, Harpsichord and Percussion, performed by Thurston Dart and the Boyd Neel Orchestra. The following year, 1957, was Stravinsky’s 75th birthday: Glock produced another special edition of The Score with a series of important essays on his music (by Keller, Sessions, Gerhard and others) and Stravinsky stayed for two weeks at the Summer School, where Robert Craft directed performances of his music.

LEFT: Igor Stravinsky, Dartington 1957, photograph by Catharine Scudamore (Dartington Summer School Foundation) RIGHT: Donald Swann, Michael Flanders, Jeremy Wilson, John Amis and Beatrice Musson, Dartington 1954, photograph by Catharine Scudamore (Dartington Summer School Foundation)

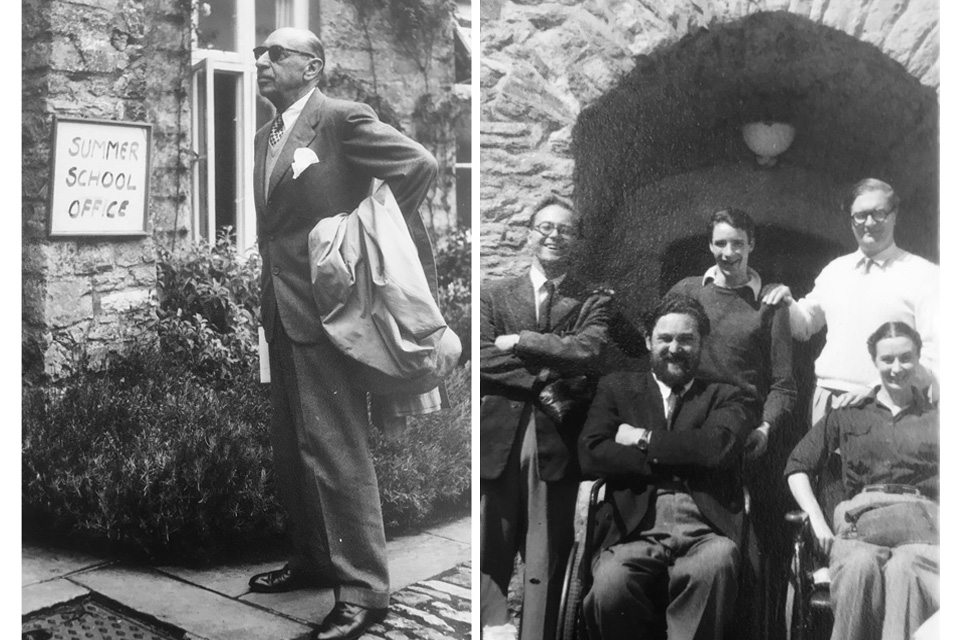

The Summer School was now THE place for musicians to be, but despite the excitement of Stravinsky’s visit and the Summer School’s forthcoming tenth anniversary, the future was by no means assured. Financially it was always a struggle to make ends meet, and the unique combination of education and festival meant that it was eligible neither for Ministry of Education nor Arts Council funding. The Summer School had very nearly folded in 1949, when its initial financial backer, Schnabel’s friend Gwynn Jones, pulled out. After that Glock formed a limited company with John Amis and Beatrice Musson (who together ran the Summer School’s administration) and the three of them took personal responsibility for its finances — which meant committing themselves to the permanent anxiety of constant fundraising and a daily watching of the booking figures. More than once they had to forego or cut their own salaries in order to balance the books, and some of their artists and teachers did the same.

The last photograph above right shows John Amis (back right) and Beatrice Musson (front right) with some of their office staff at the 1954 Summer School: in the centre of the back row is Jeremy Wilson, who had been involved in the Summer School since its earliest days (when he was a sixth-former at Bryanston School) and later became its archivist. At the back on the left is John Amis’s old schoolfriend Donald Swann, who came to help out in the office that year, bringing his friend Michael Flanders (front left). Their comic songs were the toast of the Summer School’s Friday-night cabarets, just before they found fame on the London stage with their wildly popular two-man revue At the Drop of a Hat a couple of years later.

The Summer School’s move to Dartington had improved the finances to some extent, with more and better accommodation and a guaranteed four-week stay rather than the three weeks that was usually all that Bryanston School could manage. On the other hand, fundraising was sometimes hampered by the erroneous belief that being housed at Dartington meant that the Summer School was bankrolled by the Elmhirsts (which it wasn’t — although the Elmgrant Trust did give an annual grant to fund student bursaries, the Summer School otherwise paid its way as an independent venture).

Tight as the finances were, they were not the principal worry as 1957 turned into 1958, for Glock was more affected by outside events. His work for the ICA was severely compromised when the BBC withdrew its co-operation following major cuts to its radio services as a result of the advent of television. ‘Desperate news,’ wrote Glock in his diary — but there was more to come. The International Musicians Association, which had been funding The Score (and whose London clubhouse Glock was also running) suddenly closed, leaving him without a major part of his income and an £800 hole in the journal’s budget. ‘William is facing something of a crisis,’ wrote a concerned John Amis to the Dartington Arts Administrator Peter Cox. ‘He doesn’t get any younger and where has he got to?’[13]

Glock tried to be upbeat in the face of all this: ‘Good things usually emerge from such adversities,’ he wrote to Elliott Carter that Christmas, ‘and I daresay everything will be looking better by the summer’. [14] Indeed it was, for a couple of months later Glock was approached by the Guildhall School of Music and Drama asking him apply for the post of its Principal. Even more extraordinary, that approach was immediately followed by an even more exciting possibility, when the BBC’s Controller of Music, Richard Howgill, suggested that Glock should be a candidate to succeed him when he retired. All this threw Glock into a state of ‘some turmoil’: on the one hand was the potential of financial security and fantastic opportunity — but on the other (as he wrote in his diary that evening), ‘it might b. well mean giving up being director of the Summer School, which is a bitter aspect.’[15]

William Glock and the Lindsay String Quartet, Dartington Hall 1979, photograph by Charles Davies (Dartington Summer School Foundation)

In the end, Glock managed to persuade the BBC to let him do both, convincing his bosses that the Corporation could only benefit from being associated with the Summer School — an institution now ‘famous for its standards and for its progressive policy’. For himself, the stimulation of practical music-making and exchange of ideas with some of the greatest musicians in the world was essential, and the new things he encountered at the Summer School each year fed into what he was doing at the BBC. ‘So long as you wish you have me as Controller, Music,’ he wrote to Director of Sound Broadcasting, Lindsay Wellington, ‘I shall insist on not going to sleep; and the Summer School would be an effective insurance against that ever happening.’ [16]

Glock’s commitment to the Summer School long outlasted his BBC post, from which he retired in 1973. He stayed in charge of the Summer School for a full three decades, finally leaving in 1979, having arranged for Peter Maxwell Davies to succeed him. The picture above shows him in his very last season at Dartington, playing Schumann’s Piano Quintet in E flat Op.44 with the Lindsay String Quartet, who can also be seen in the drawing below by Milein Cosman, being coached by the Viennese émigré violinist and quartet leader Rudolf Kolisch at Dartington in 1965.

Rudolf Kolisch and the Lindsay String Quartet, Dartington 1965, drawing by Milein Cosman, © The Cosman Keller Art & Music Trust

Further reading:

William Glock, Notes in Advance, Oxford University Press, 1991

Harriet Cunningham, Creative hotspot: a cultural history of Dartington International Summer School of Music, 1953-59, PhD Thesis, Sydney University of Technology, 2019

Barrie Gavin, A Few Yards out to Sea, a film on William Glock and Dartington, 1988 (available on YouTube).

The Royal College of Music is creating a searchable database of all the repertoire, performers and teachers at the Summer School during its early years: the first six years are available .

Photographer Kate Mount’s archive of images from more recent Summer Schools can be explored on her website.

The Summer School celebrated its 75th anniversary in 2023, after which the Dartington Trust (which has run the Summer School since the 1990s) put future plans on hold, due to urgent financial challenges. In 2024 the Dartington International Summer School Foundation (which has been supporting the Summer School since1976) announced that it would run a Music Summer School and Festival at Gresham's School in Norfolk in July-August 2024, with the aim of securing the future of the Summer School, providing continuity for its long-standing musical community and preserving the legacy of all that has been achieved so far.

Endnotes

1 Letter from Susan Bradshaw to William Glock, 17 March 1988, BL MS Mus. 949

2 William Glock, Notes in Advance, Oxford (OUP), 1991; 19

3 Letter from William Glock to Marjorie Glock, undated, BL MS Mus. 953

4 Letter from Nadia Boulanger to William Glock, 28 February 1948, BL MS Mus. 948

5 Glock, Notes in Advance; 57

6 Ibid. 54

7 Ibid. 54

8 Letter from Susan Bradshaw to William Glock, 17 March 1988, BL MS Mus. 949

9 Bradshaw, ‘Hans Keller: Memorial Symposium’, Music Analysis V 2/3 (July-October 1986); 377

10 Wood, ‘Hans Keller Memorial Symposium’; 398

11 Glock, Notes in Advance; 60

12 Ibid. 57

13 Letter from John Amis to Peter Cox, 23 February 1958, BL uncatalogued

14 Letter from William Glock to Elliott Carter, 2 January 1958, BL MS Mus. 950

15 William Glock, diary entry, 22 October 1958, BL MS Mus. 979

16 Letter from William Glock to Lindsay Wellington, 24 September 1959, BBC WAC L2/84/1