This story is about the Anglo-Austrian Music Society founded in London in 1942 by Ferdinand Rauter with the help of refugee musicians and some British-born supporters.

Author: Beth M. Snyder

Introduction

The Anglo-Austrian Music Society—which was in existence until only a few months ago—was founded in London in 1942 by Ferdinand Rauter with the help of refugee musicians Georg Knepler and Hermann Ullrich, and a handful of British-born supporters including folk dancer and researcher Maud Karpeles and diplomat John Holroyd-Reece. Rauter was an Austrian-born musician, pedagogue, and amateur mycologist who had made his name arranging and performing songs from various folk traditions with soprano Engel Lund.

Engel Lund and Ferdinand Rauter at the piano, 1934 (credit: Howard Coster, photographer)

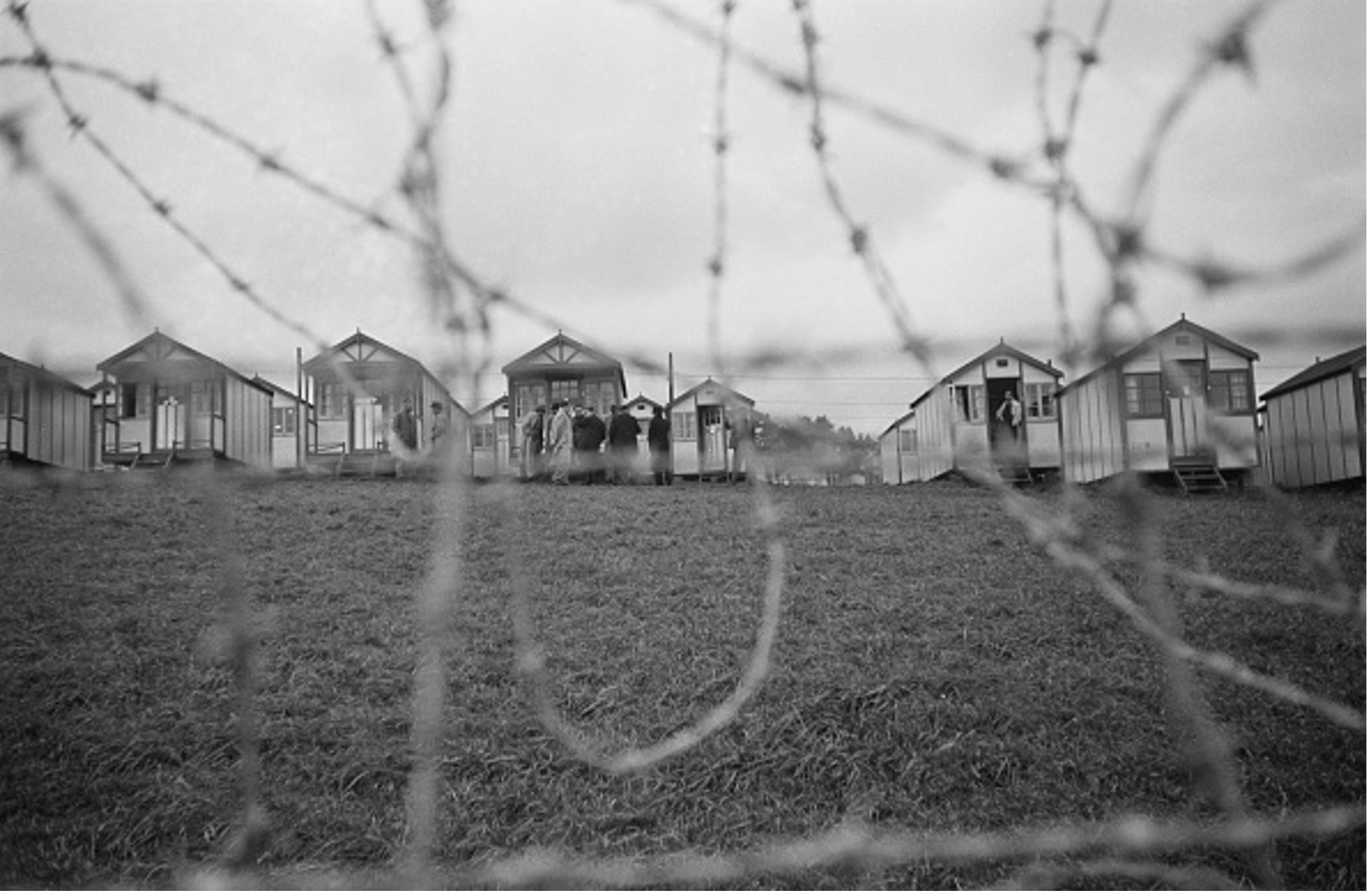

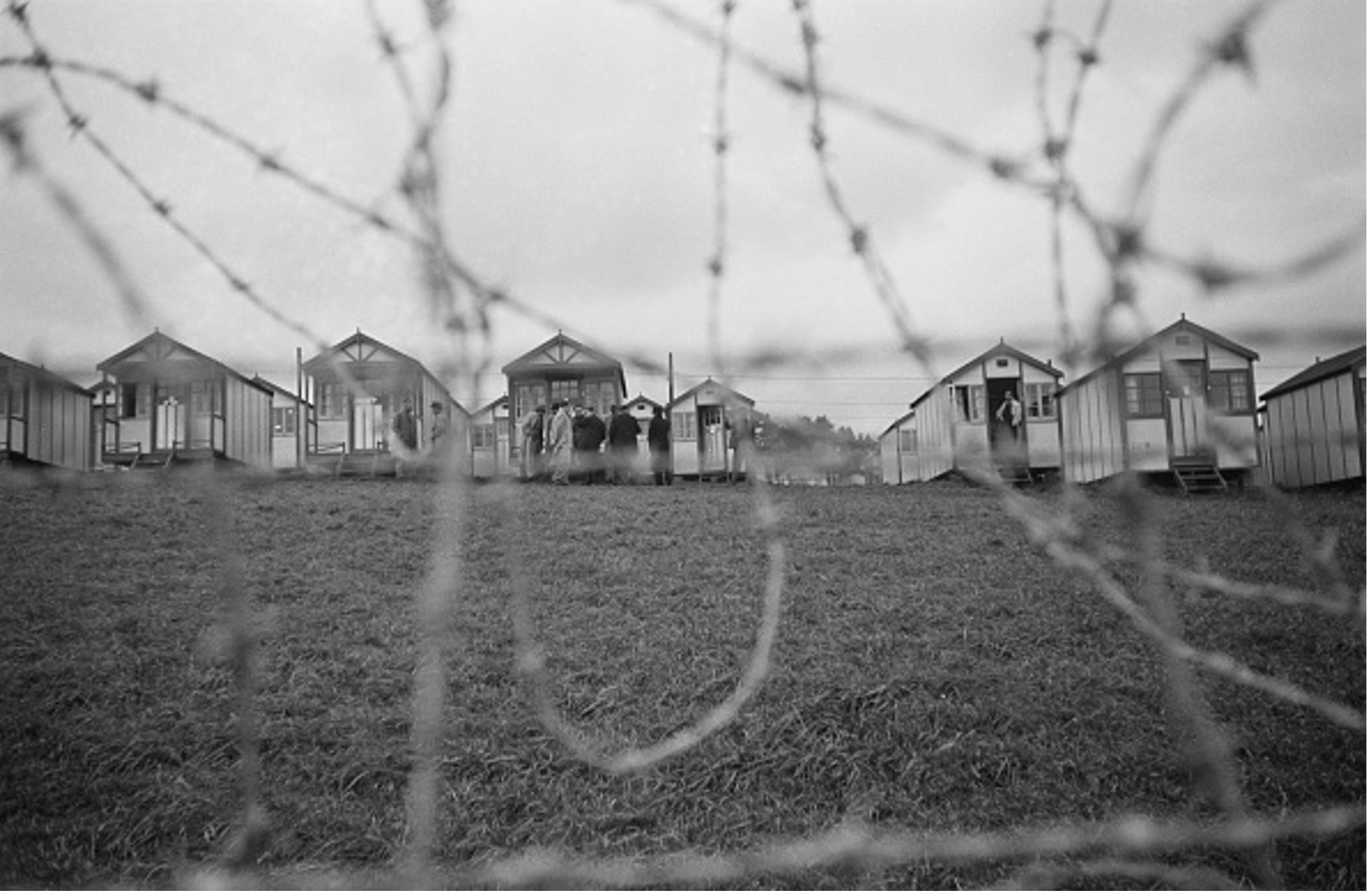

He spent much of 1940 interned on the Isle of Man as an ‘enemy alien’, a designation visited upon some 70,000 German, Austrian, Italian, Japanese, and Finnish refugees and residents in the United Kingdom during the Second World War.1

View of an internment camp in England through barbed wire, c. 1940 (credit: Getty Images, Popperfoto Collection)

In the wake of that internment, Rauter helped to found a series of musically oriented organisations culminating with the Anglo-Austrian Music Society. The aims of those organisations were two-fold: to gain release from internment for musicians who had migrated by force or choice (or some combination thereof); and to help ensure that those musicians could support themselves financially as artists and participate fully in Britain’s musical life.

Ferdinand Rauter and the founding of the Society

The Anglo-Austrian Music Society and its precursor organisations arose, then, in part from the constrained mobilities of migrant and refugee musicians during the war. It was also made possible by Ferdinand Rauter’s post-internment ease of movement through British musical circles, as someone who had not been a refugee and who had been active in British musical life for many years.2

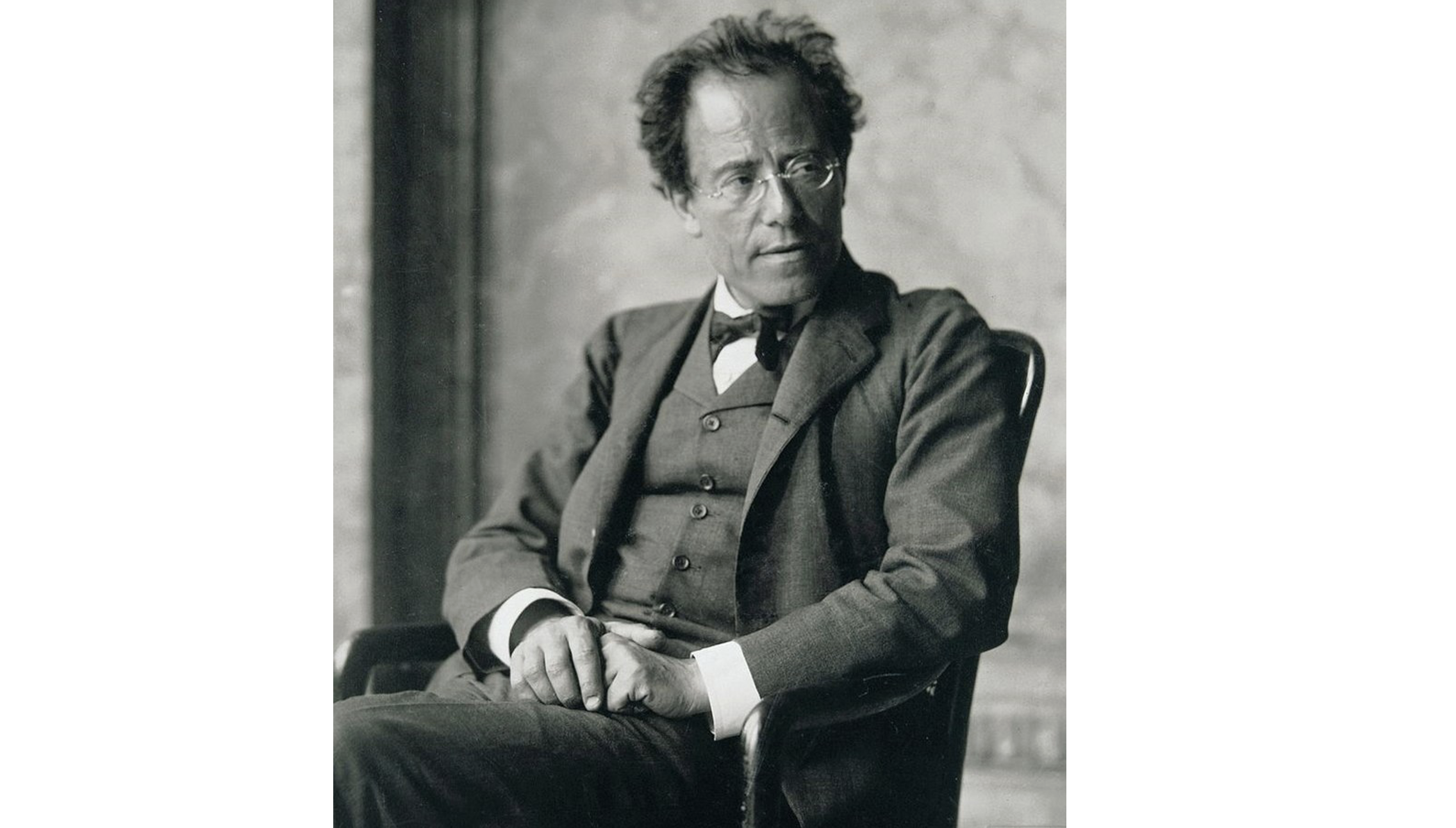

Rauter, who had been born in Klagenfurt in 1902, studied both music and chemistry in Dresden. It was there, in 1929, that he first met singer Engel Lund, with whom he would form an enduring creative partnership, touring with her throughout Britain, Continental Europe, and the Americas during the early 1930s and beyond.3 Neither Rauter nor Lund had Jewish heritage, but both were staunch critics of the Nazi regime. Thus, they decided it prudent to relocate their base of operations from Germany after 1933—first moving to Copenhagen, where Lund’s family was living, and, in 1935, to London, where the duo’s management agency, Ibbs & Tillett, was located.4

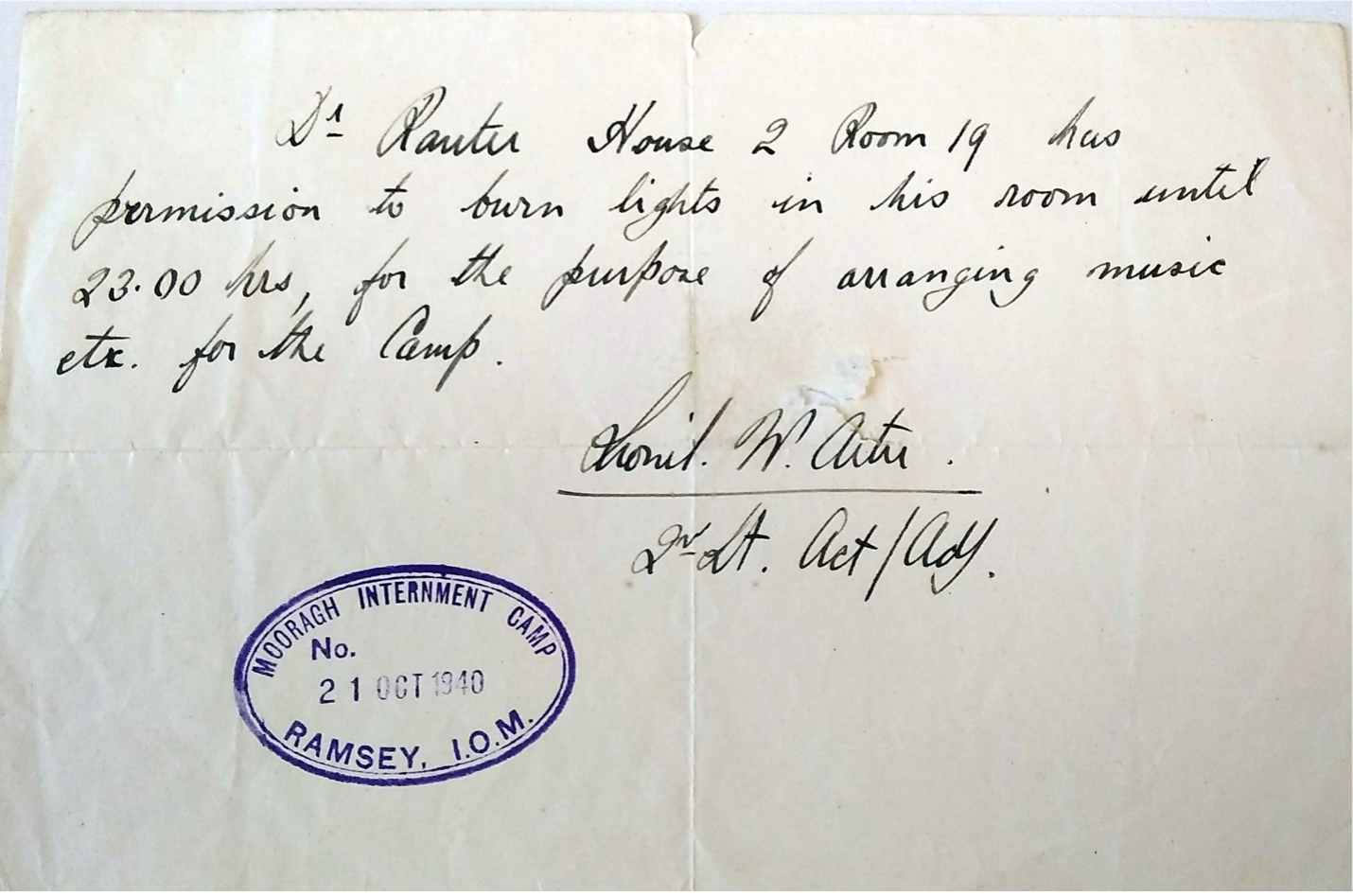

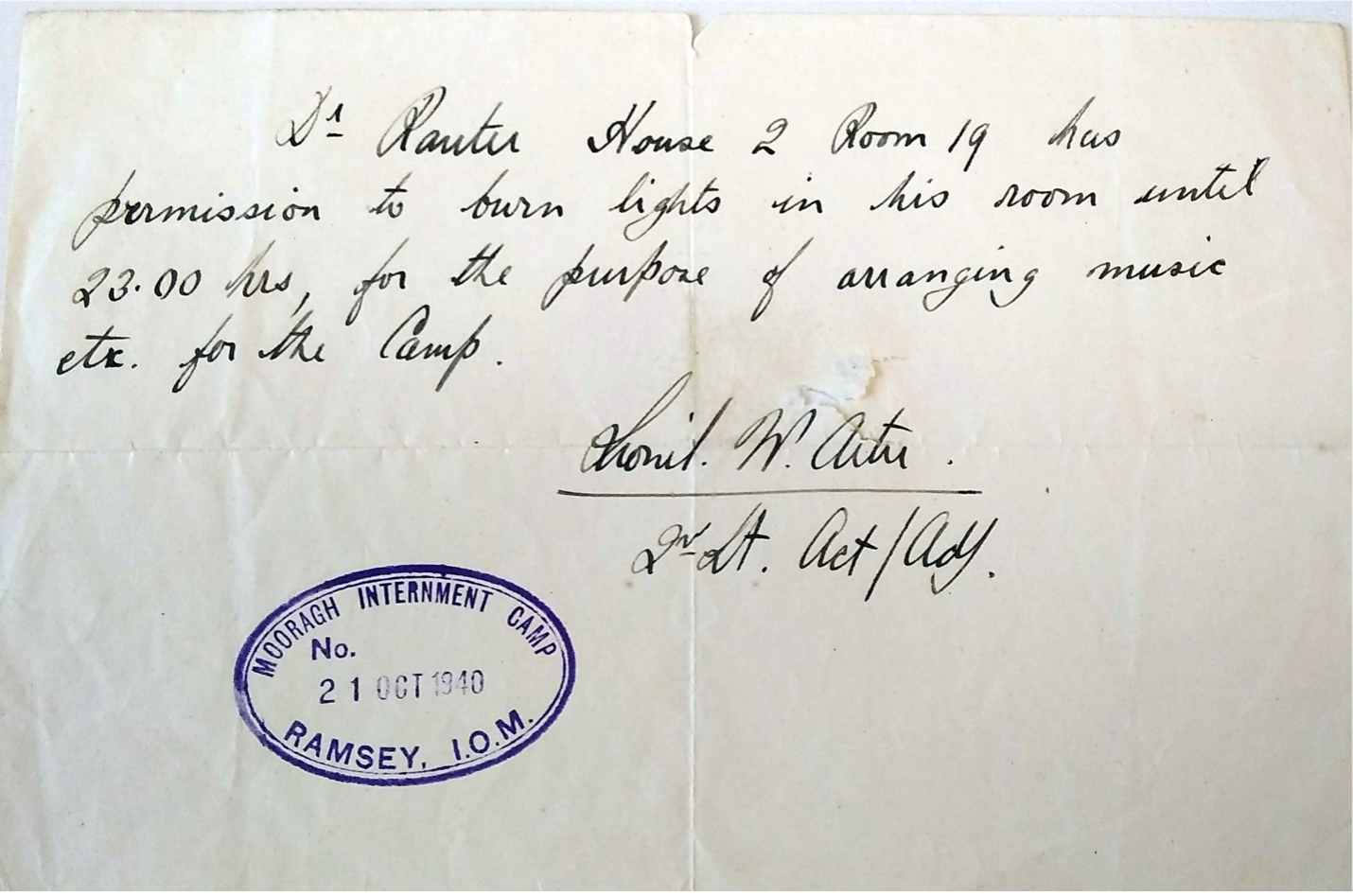

Following the declaration of war, Rauter was interned in May of 1940. During his time at the camps, he met and made music with a number of musicians—including Norbert Brainin and Peter Schidlof (who would later become half of the Amadeus Quartet).5 As Rauter was a well-known and respected musician, he was granted a greater degree of movement within the camps in order to arrange music and organise performances and lectures.

Pass issued to Ferdinand Rauter allowing him to burn lights until 23.00 hours in order to arrange music, 21 October 1940 (Ferdinand Rauter Archive, Salzburg Music and Migration Collections, University of Salzburg)

Due to the tireless efforts of Lund and the support of luminaries of British musical life like Ralph Vaughan Williams, Rauter became one of the first musicians to be released from the camps (in December 1940) after 23 weeks of internment.

A mere month after being released, Rauter helped to found the Refugee Musicians Committee. That Committee included Maud Karpeles, Georg Knepler, and the likes of Ralph Vaughan Williams, pianists Dame Myra Hess and Harriet Cohen, and Royal College of Music Director, George Dyson. The immediate goals of the organisation were to get musicians out of internment, to get young musicians pursuing music studies in Britain and to secure work permits for more established migrant and refugee musicians.

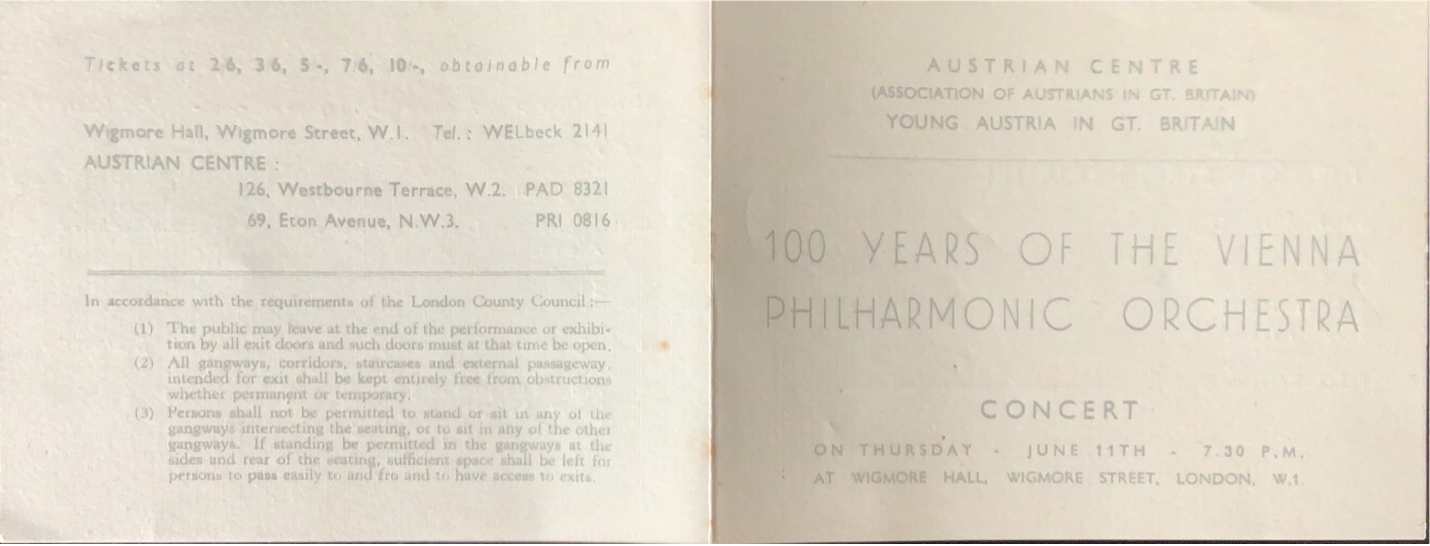

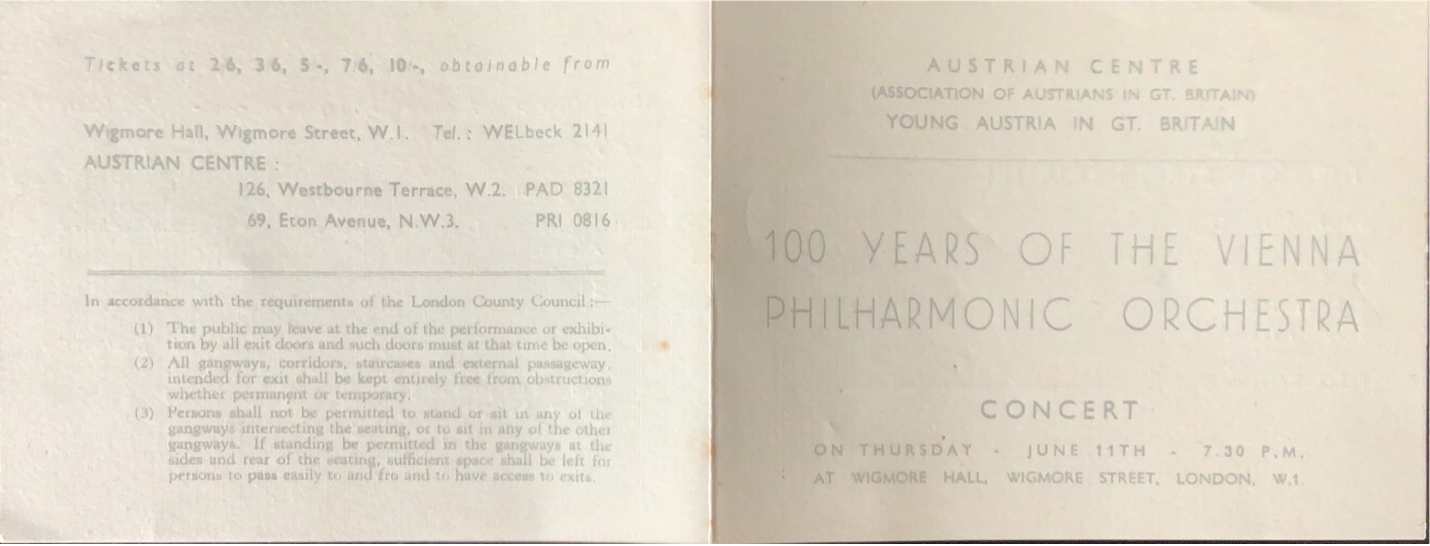

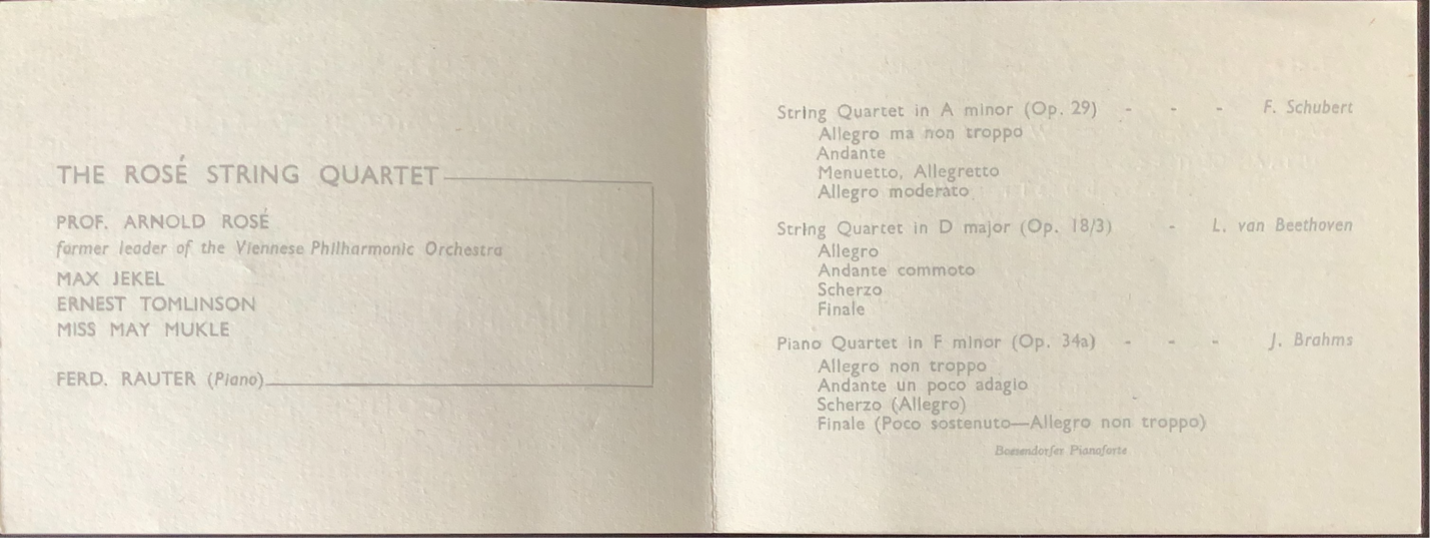

By late spring of 1942, the RMC had morphed into the AMG—the Austrian Musicians Group—which Rauter co-founded with Knepler and Ullrich. The adoption of a nationalist orientation accorded with the general proliferation at this time of societies aimed at establishing community amongst particular migrant groups in Britain. The activities of the AMG primarily entailed the organisation of concerts (where many musicians had previously only been able to perform in private homes). The inaugural concert of the AMG took place in summer of 1942 at the Wigmore Hall with a celebration and symbolic reclamation of the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra.

Leaflet announcing the programme of the first concert of the Austrian Musicians Group, ‘100 Years of the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra,’ 11 June 1942 (Private Collection of Andrea Rauter)

Leaflet announcing the programme of the first concert of the Austrian Musicians Group, ‘100 Years of the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra,’ 11 June 1942 (Private Collection of Andrea Rauter)

Rauter, who had become concerned with both the long-term financial viability of the AMG and with its ties to organisations like the Free Austria Movement, chose to step away from the group in autumn 1942. He sought, as well, a way to engage British-born patrons and audiences more directly, and with that concern in mind, formed what would come to be known as the Anglo-Austrian Music Society at the end of 1942. In order to shore up British support for the nascent organisation, Rauter once again sought help from Vaughan Williams, asking the composer to serve as Honorary President of the AAMS. What followed was a trio of letters, wherein Vaughan Williams initially demurred, expressing an anxiety that the influx of foreign artists in Britain would ‘entirely devour the tender little flower of our English culture.’ Rauter, for his part, attempted to reassure Vaughan Williams, recasting relations between British- and Austrian-born musicians as being mutually beneficial, providing an opportunity to cultivate ‘real understanding between the British and ourselves, resulting in a mutual fertilisation of ideas.’ Rauter concluded his letter by once again taking up Vaughan Williams agricultural metaphors, claiming: ‘we can work as friends and brothers and in a happier future reap what we have sown together.’ Although Vaughan Williams remained skeptical, he did, to his immense credit, agree to offer the power of his name and patronage to the Society.6

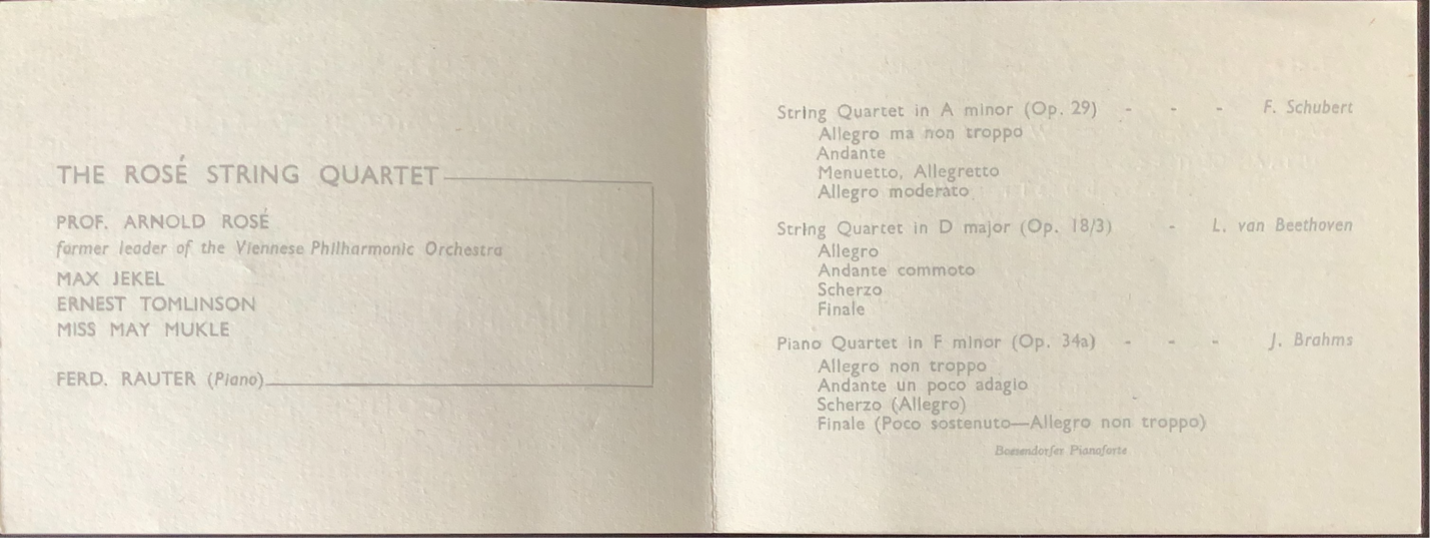

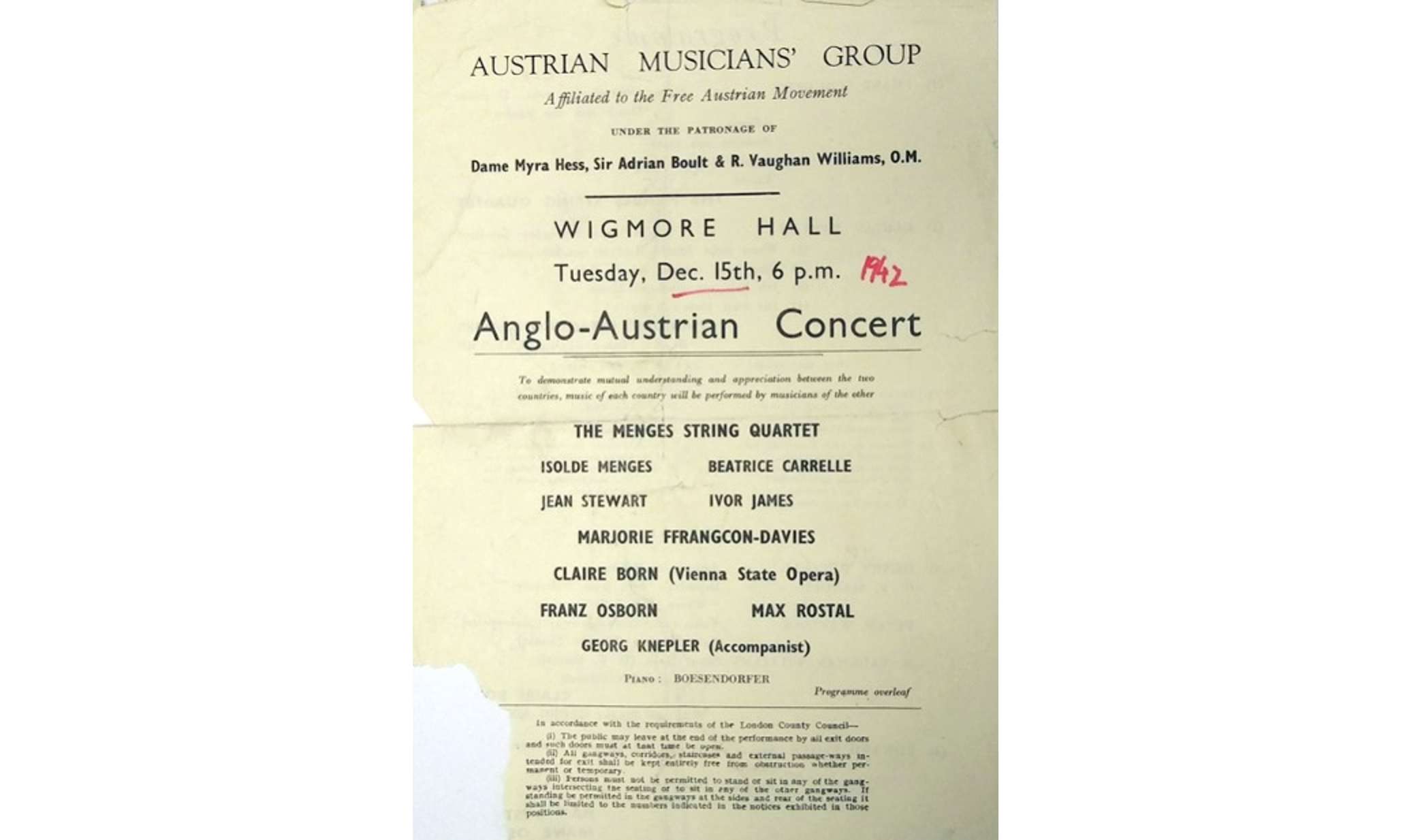

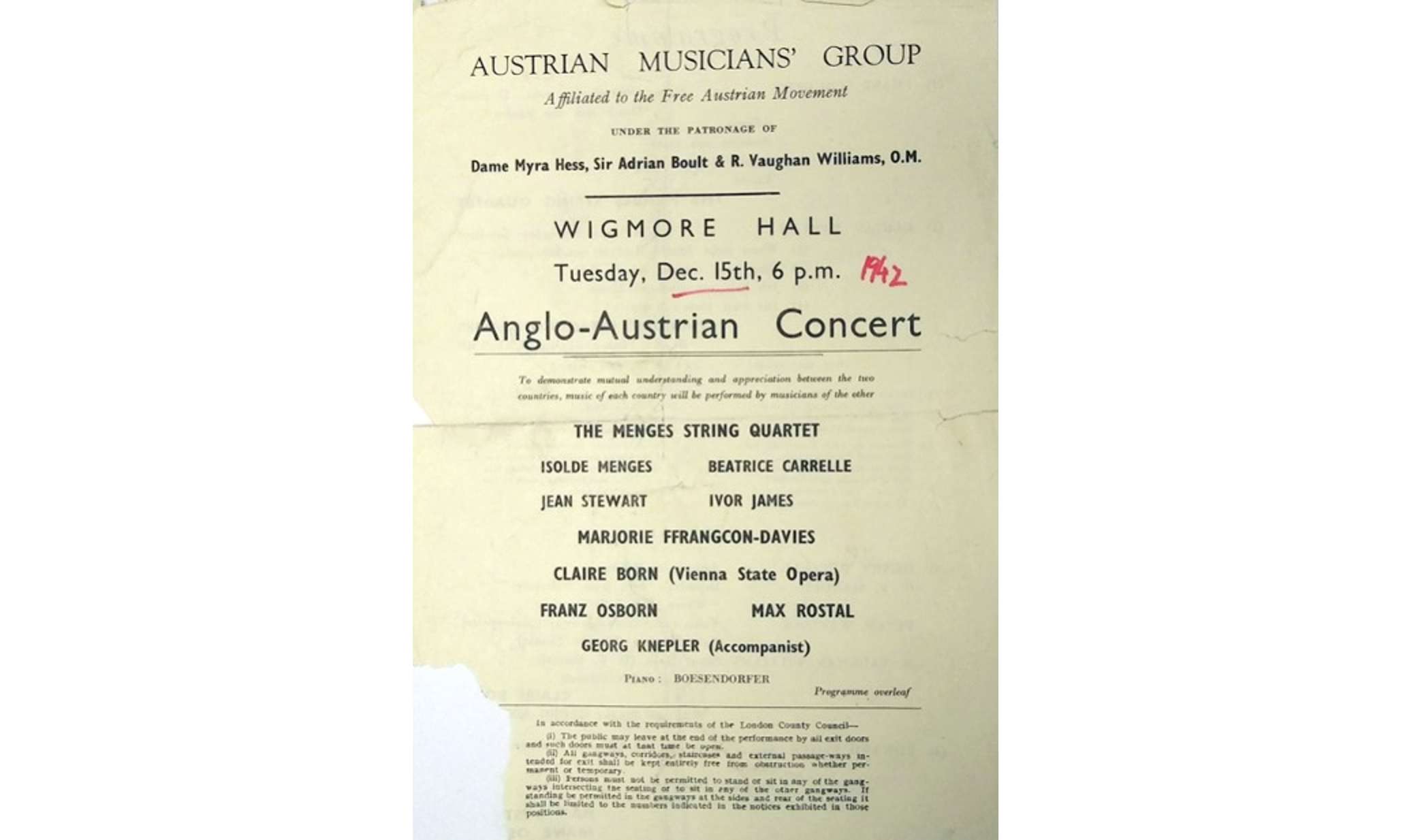

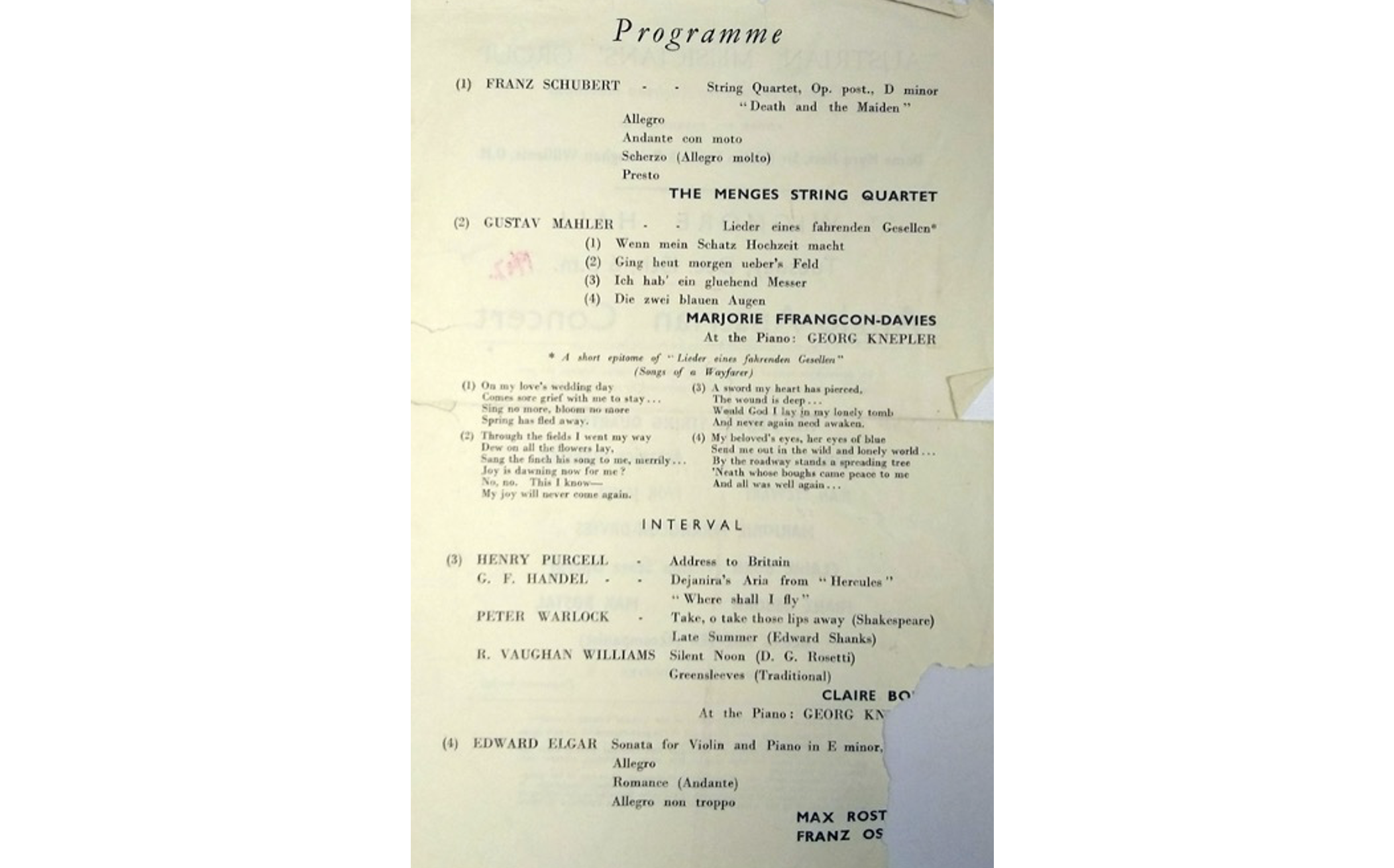

The inaugural concert of what was then known as the Society of Friends of the Austrian Musicians Group (but changed its name to the Anglo-Austrian Music Society a few short months later) took place in the Wigmore Hall on 15 December 1942.

Programme of the inaugural concert of what would come to be known as the Anglo-Austrian Music Society, 15 December 1942 (Ferdinand Rauter Archive, Salzburg Music and Migration Collections, University

Programme of the inaugural concert of what would come to be known as the Anglo-Austrian Music Society, 15 December 1942 (Ferdinand Rauter Archive, Salzburg Music and Migration Collections, University

The concert programme was constructed faithfully on the principle of mutual fertilisation and the goal of shared projects and futures that Rauter emphasized in his correspondence with Vaughan Williams—British-born musicians performed the works of Austrian-born composers and vice versa.

The personnel and activities of the Society

Rauter remained closely involved in the organisation of the Society’s activities and concert programming throughout the war years, working closely with an Executive Committee that initially included Karpeles, Ullrich, Knepler, and Holroyd-Reece. In the late 1940s Rauter’s work as driving force of the AAMS was taken up by Otto Harpner, a refugee from Austria who had earlier been involved with the Society’s sister organisation, the Anglo-Austrian Society (with whom the AAMS shared administrative staff after 1946). With Harpner’s untimely death in 1959, the torch was passed once again, this time to Walter J. Foster (born Walter Fast), who had served as Harpner’s assistant at the AAS from 1950 onward. Foster, a refugee who had come to Britain via the Kindertransport in 1938, served as General Secretary of both the AAS and AAMS from 1959 until his retirement in 1992. These three individuals—Rauter, Harpner, and Foster—worked tirelessly alongside a devoted group of colleagues—including refugees Hedi and Peter Stadlen (the latter a pianist and Webern specialist), music publisher Alfred Kalmus, Harpner’s widow Lisa, Jane and Robert Avery and many others—over the organisation’s almost 80-year existence in order to pursue the goals established during the Society’s inception.

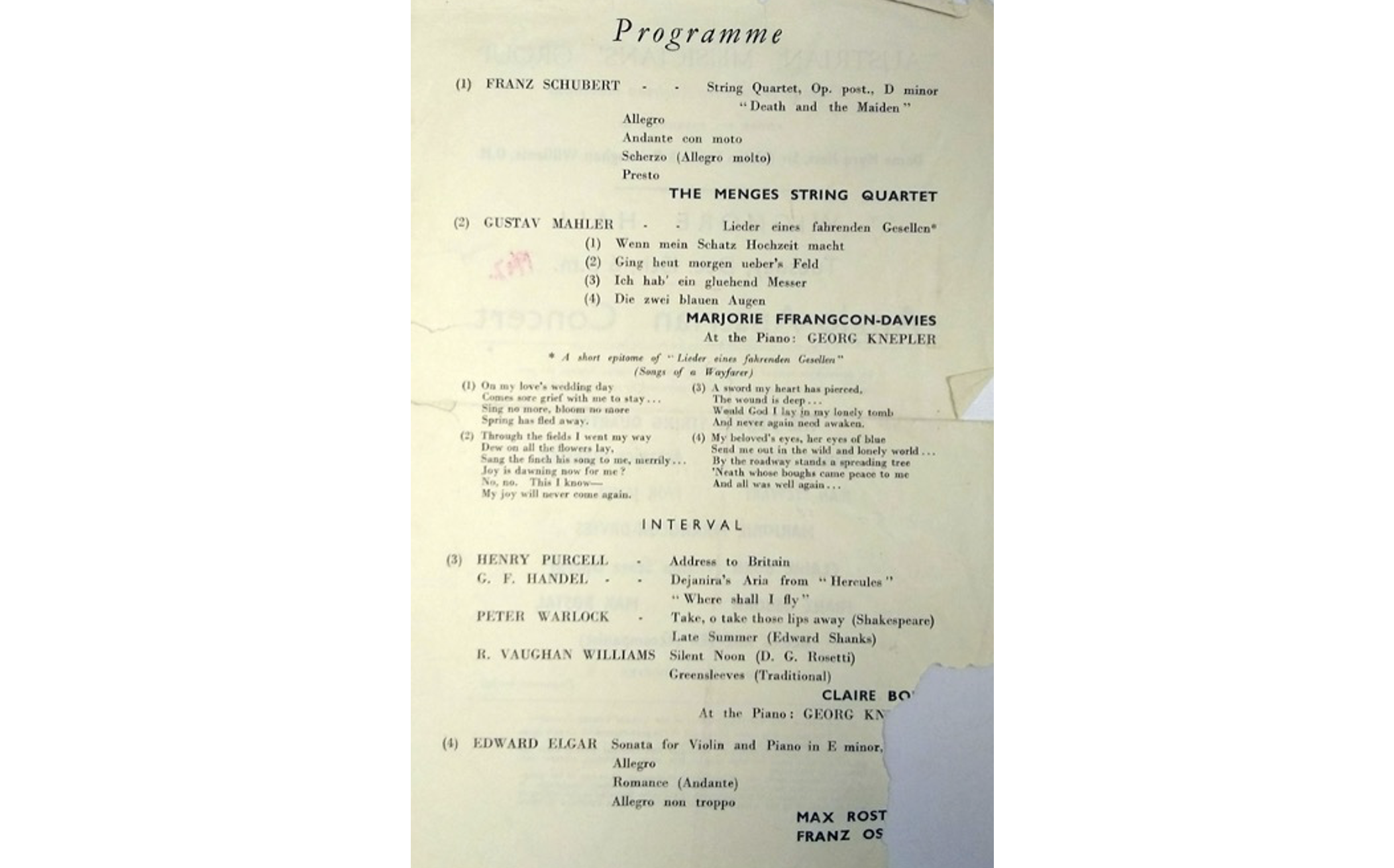

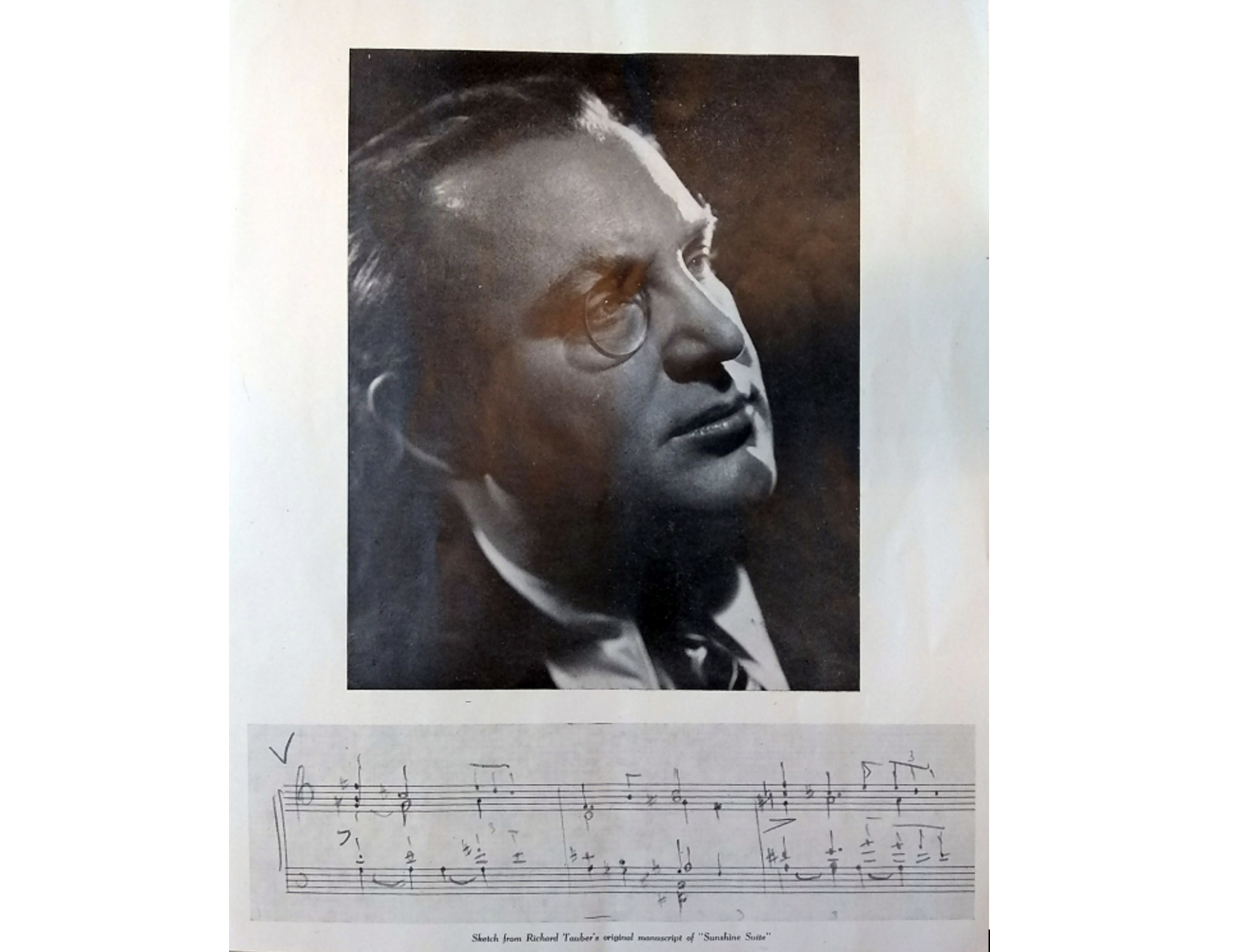

One of those goals—quite near and dear to Rauter—was the cultivation of young talent, which was accomplished during wartime and after with recitals given in private homes and at the Wigmore Hall by young musicians such as the Amadeus Quartet’s Peter Schidlof and British-born pianist Alfred Kitchin.7 This goal was pursued on a grander scale with the establishment in 1950 of the Richard Tauber Memorial Scholarship (later the Tauber Prize). Initially open only to male British singers (and becoming far more inclusive over time), it was awarded roughly every two years, and was established in honour of tenor and refugee Richard Tauber. The prize was funded at first by a Society-sponsored concert given in 1948 to memorialize the recently deceased singer and celebrate his legacy, with his last public appearance being in an AAMS-sponsored event just months prior to his death.. 8

Page from the programme booklet for the Richard Tauber Memorial Concert, 20 February 1948 (Anglo-Austrian Music Society and Anglo-Austrian Society Archive, Senate House Library, University of London)

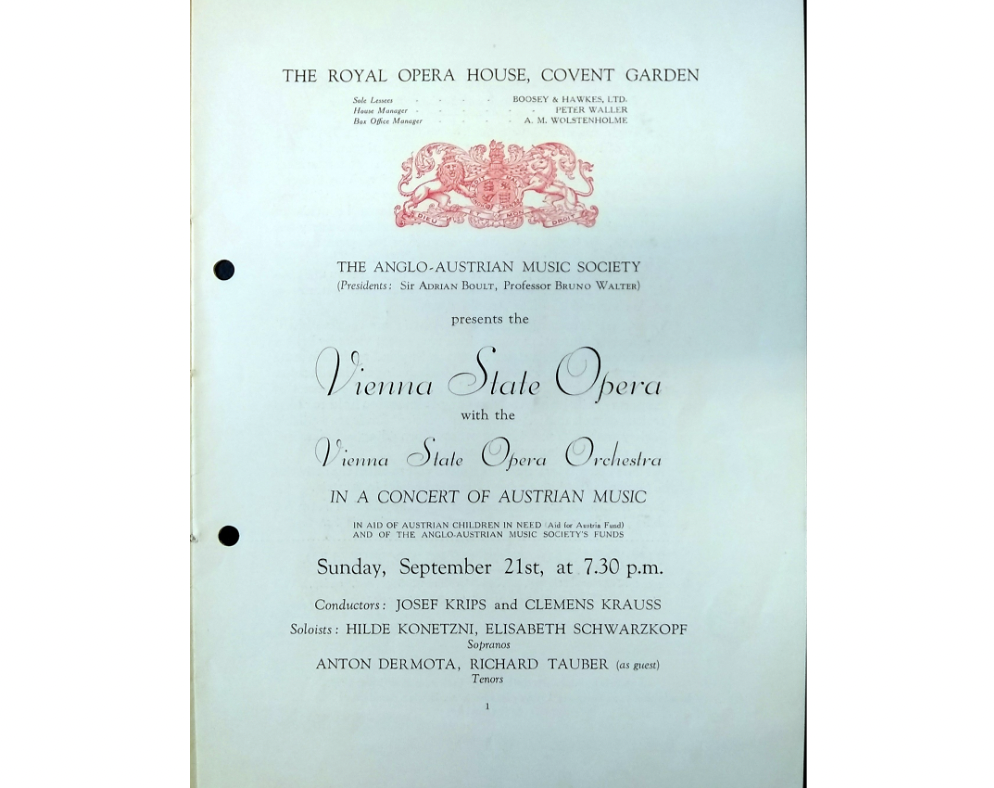

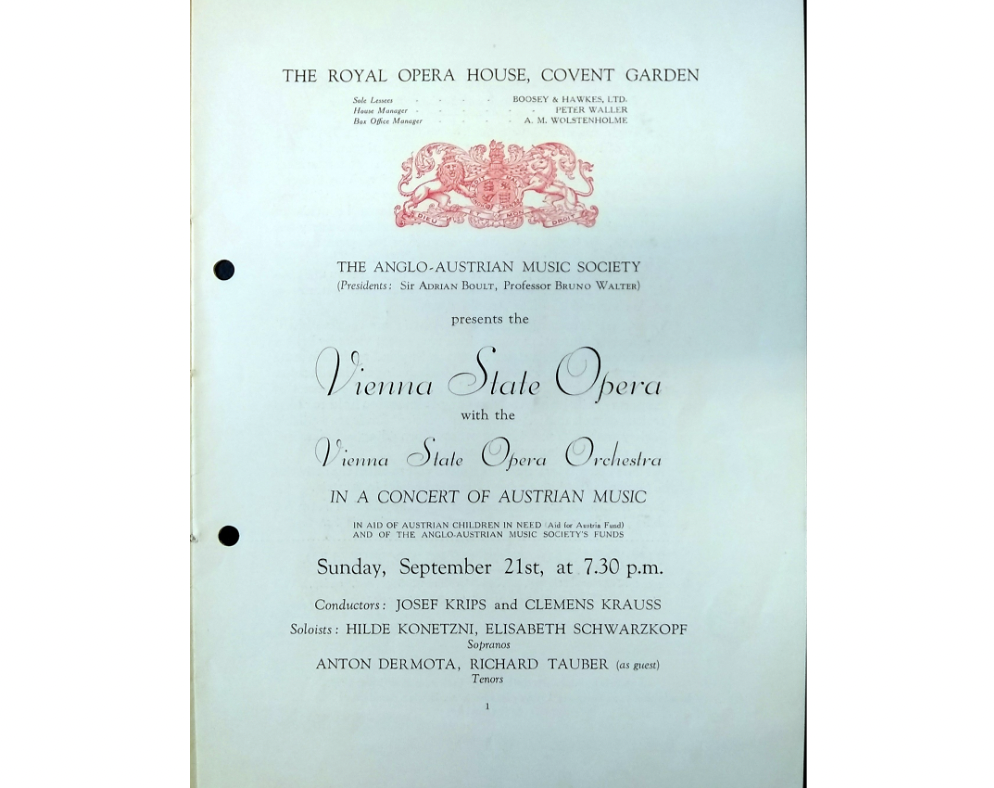

Leaflet announcing a concert with the Vienna State Opera & Vienna State Opera Orchestra featuring Richard Tauber, 21 September 1947 (Anglo-Austrian Music Society, Anglo-Austrian Society Archive, UCL)

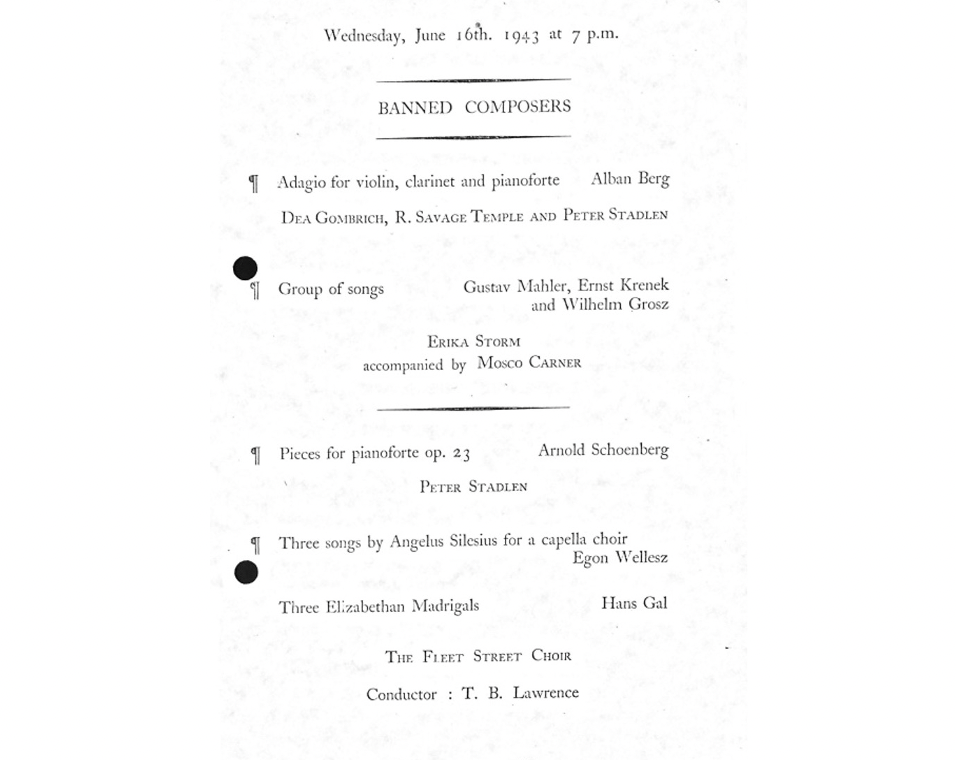

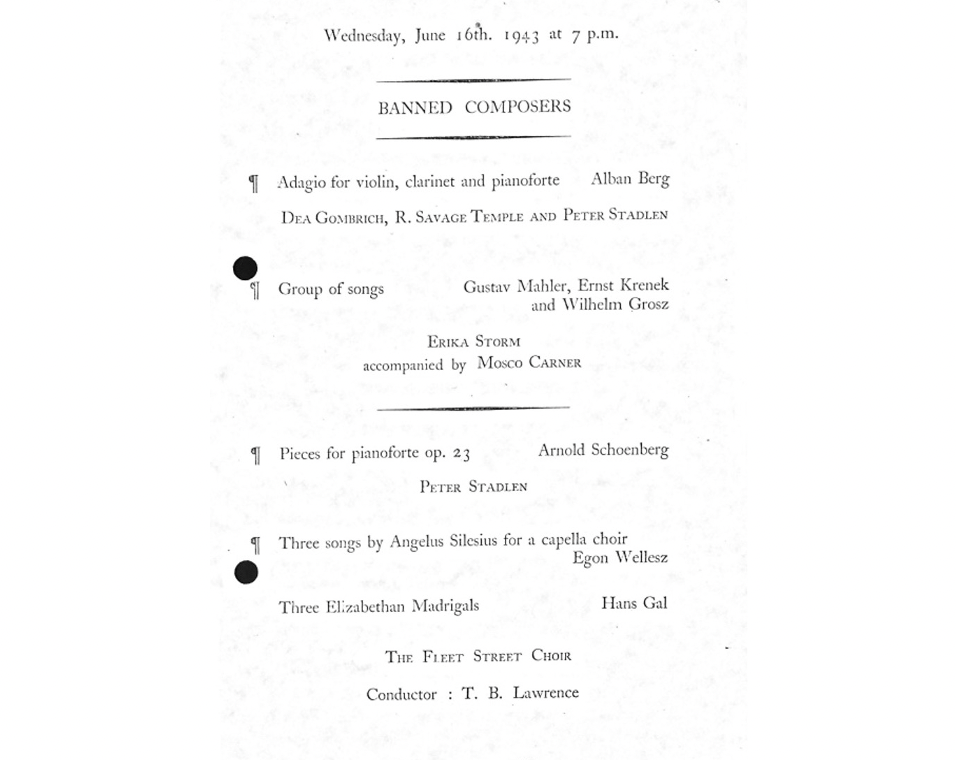

Draft leaflet for a concert programme of ‘Banned Composers’, 16 June 1943 (Anglo-Austrian Music Society and Anglo-Austrian Society Archive, Senate House Library, University of London)

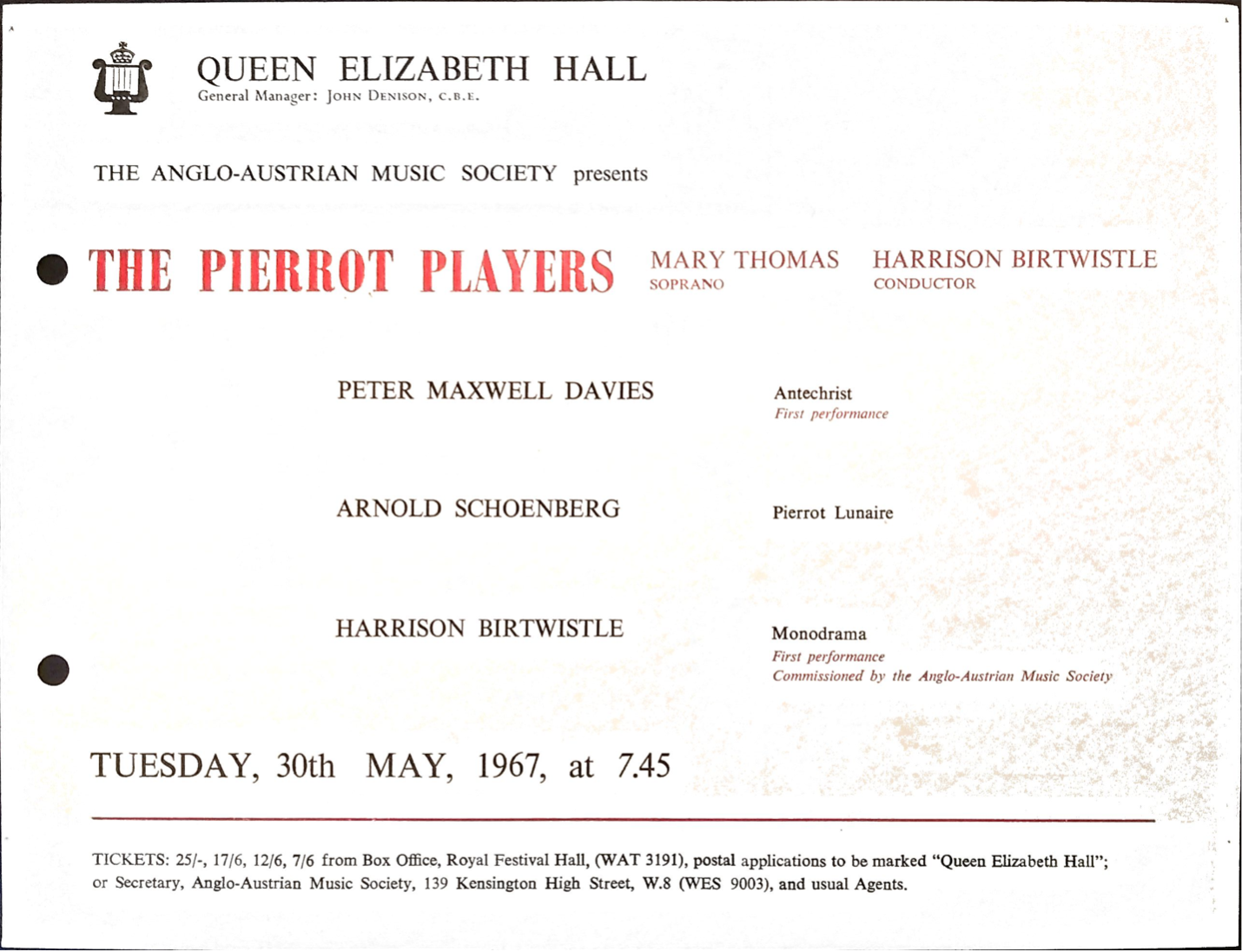

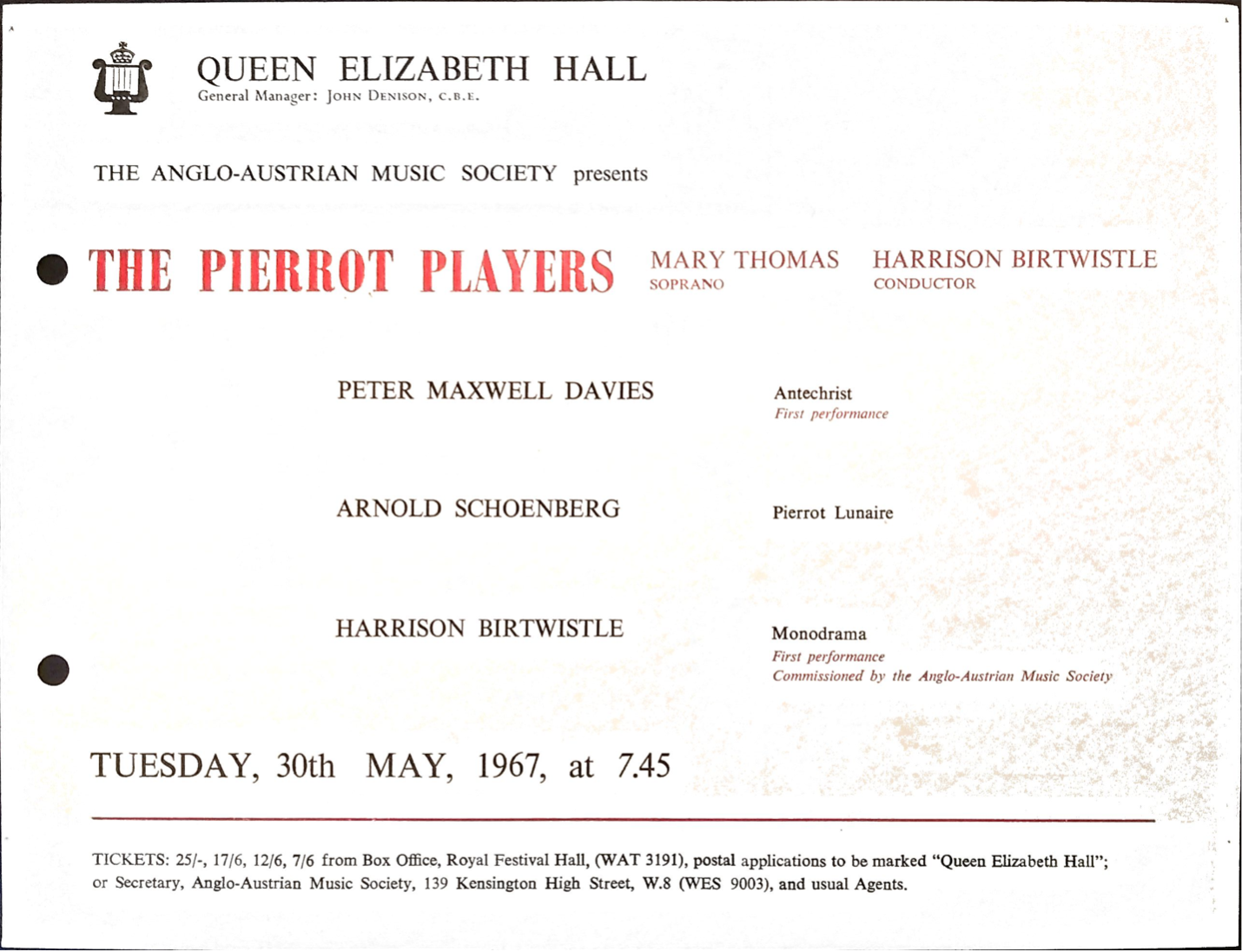

Page from programme booklet for a concert featuring works by Peter Maxwell Davies and Harrison Birtwistle, 30 May 1967 (Anglo-Austrian Music Society, Anglo-Austrian Society Archive, UCL)

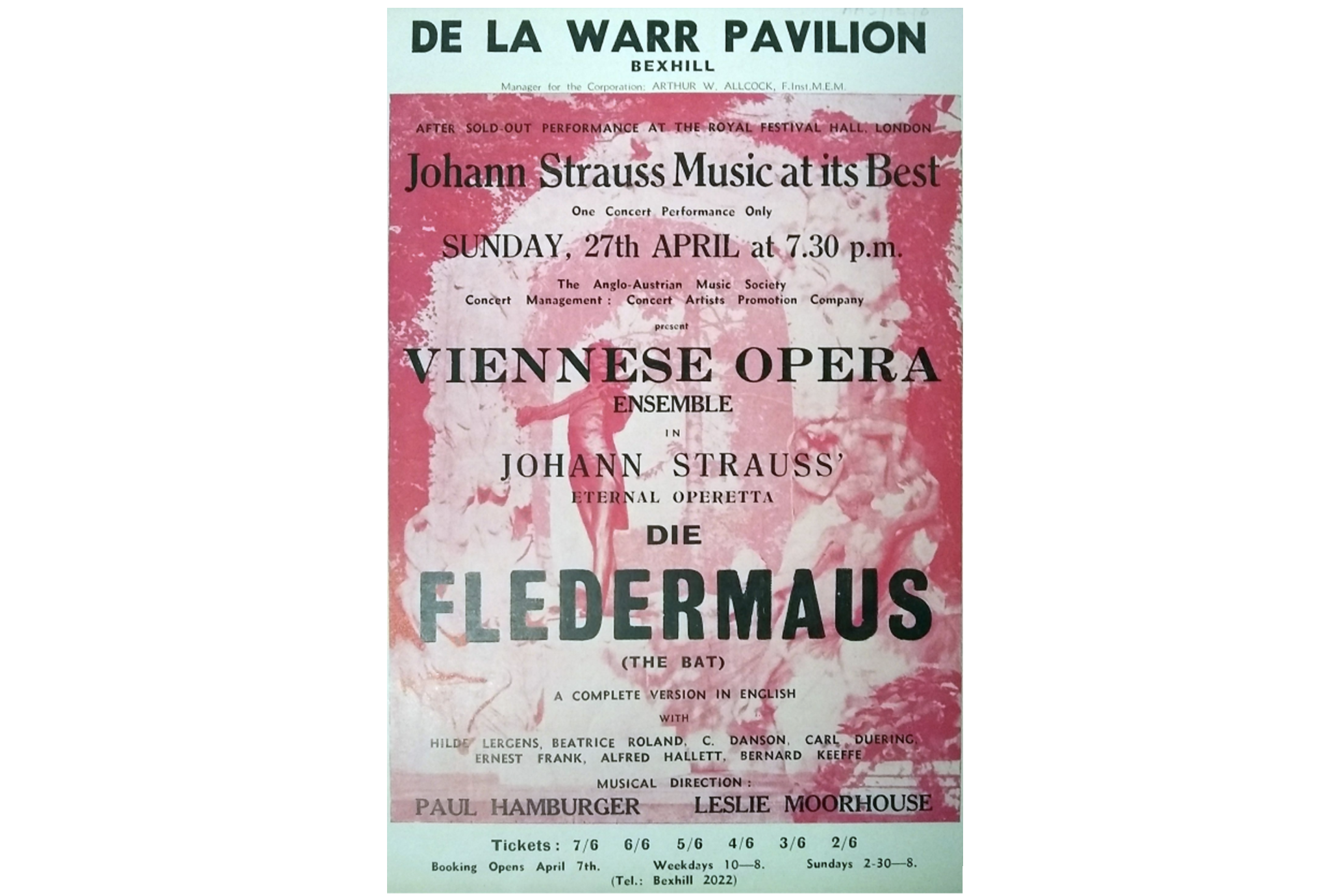

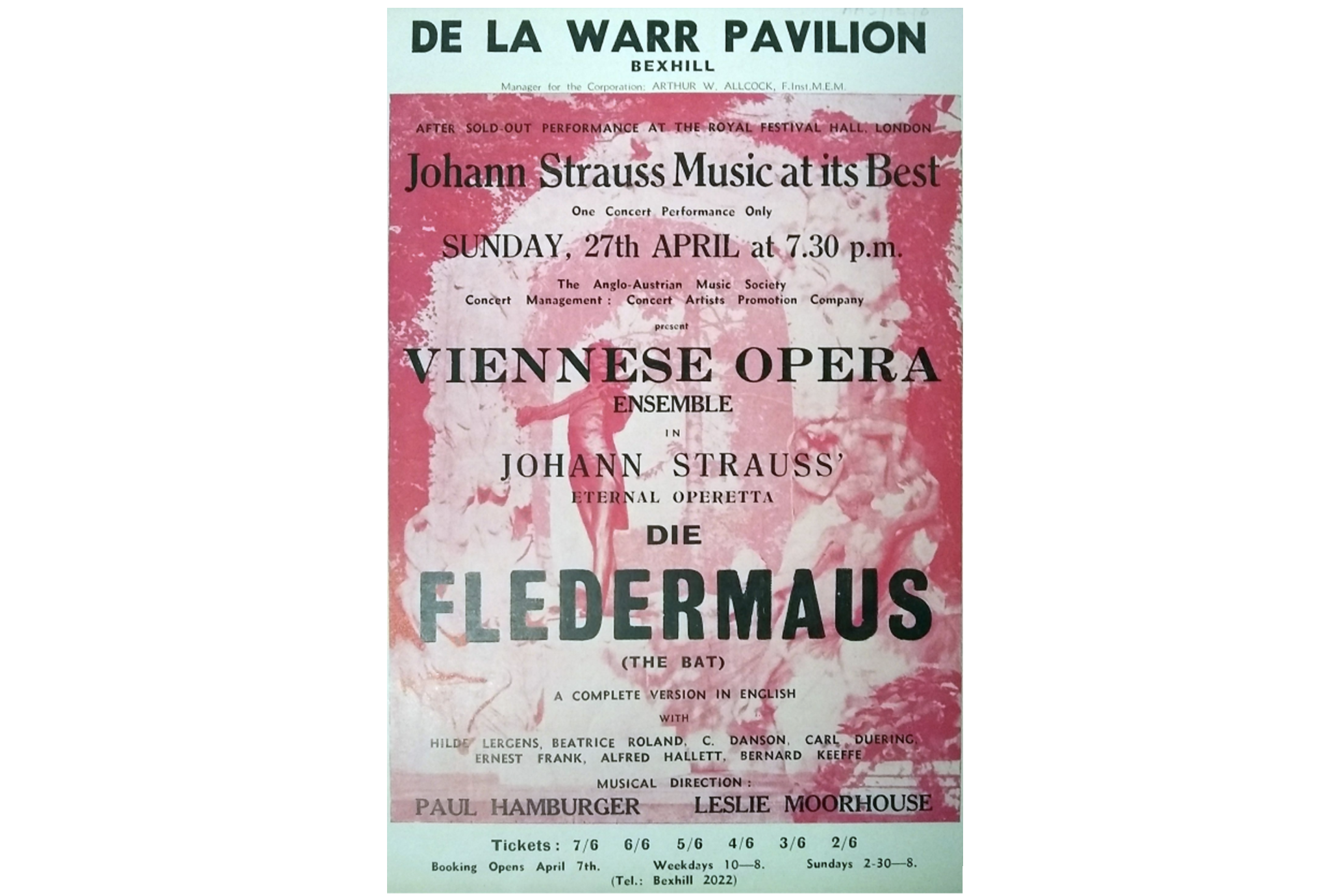

Poster announcing an English-language production of Die Fledermaus in Bexhill, part of a tour sponsored by the AAMS, 27 April 1952 (Anglo-Austrian Music Society & Anglo-Austrian Society Archive, UCL)

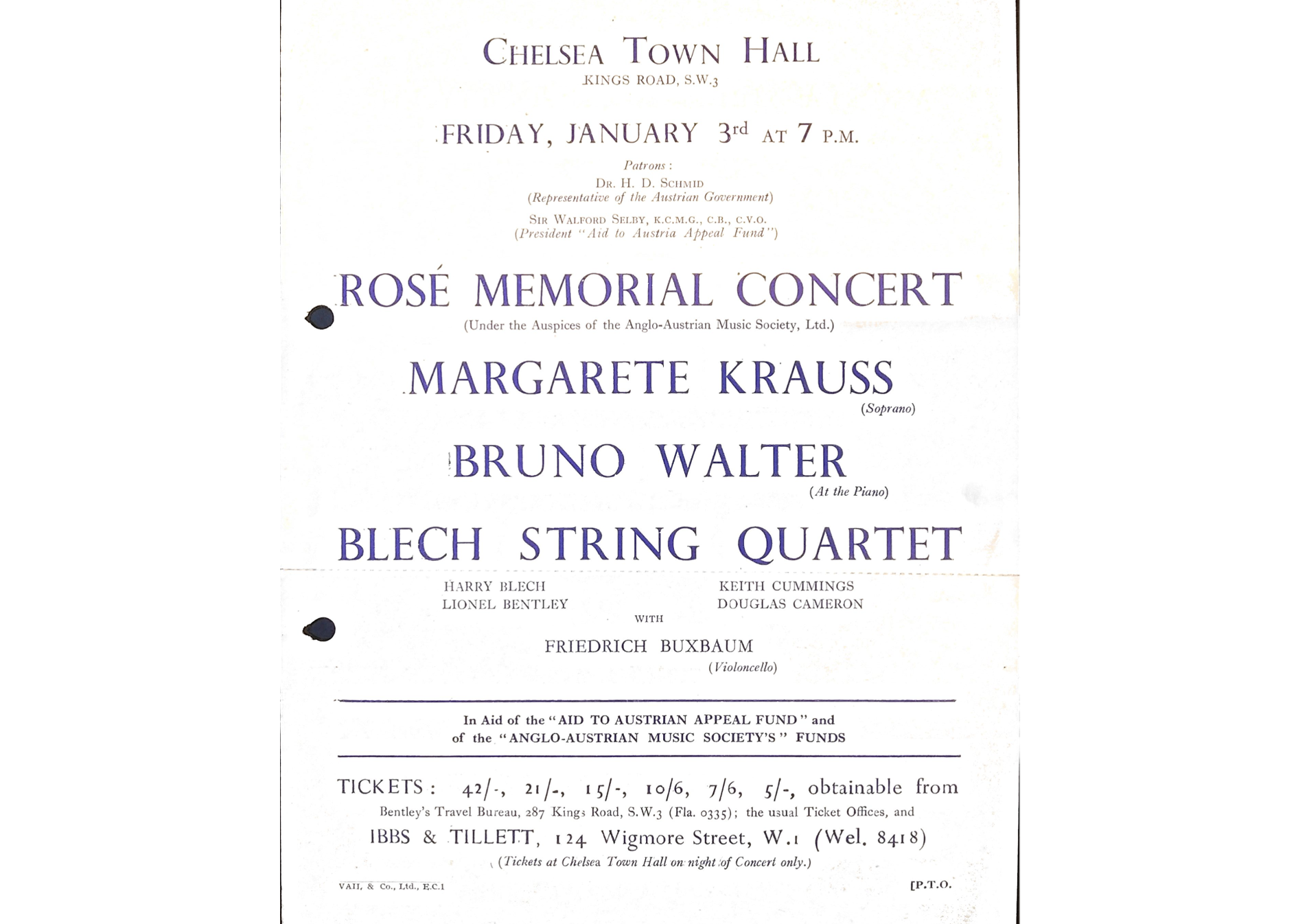

Leaflet announcing a memorial concert for Arnold Rosé at Chelsea Town Hall, 3 January 1947 (Anglo-Austrian Music Society and Anglo-Austrian Society Archive, Senate House Library, University of London.

Cover of programme booklet for Arnold Schoenberg Memorial Concert, signed by contralto Anne Wood and pianist Peter Stadlen, 1952 (Anglo-Austrian Music Society, Anglo-Austrian Society Archive, UCL)

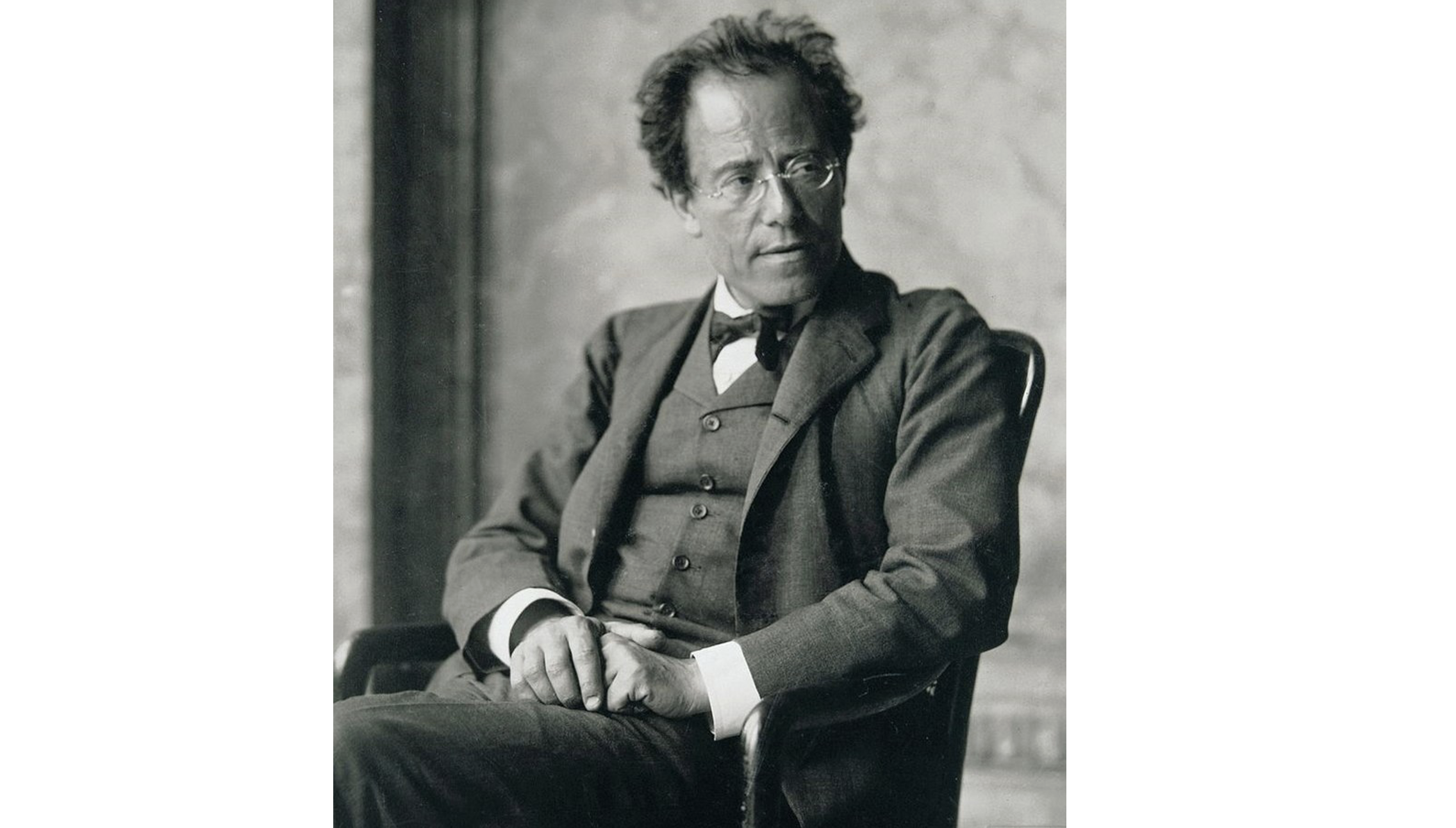

Poster announcing the Gustav Mahler Centenary Exhibition held at the Royal Festival Hall, 4-30 October 1960 (Anglo-Austrian Music Society and Anglo-Austrian Society Archive, Senate House Library, UCL)

Cover of the programme booklet for the first Society-sponsored tour of The Gay Tyrolese, 1957 (Anglo-Austrian Music Society and Anglo-Austrian Society Archive, Senate House Library, University of Lond

The goals of employing and promoting the creativity of migrant musicians living in Britain (some Austrian-born, some not) was not an isolated one. During the war, the Society, for instance, organised a concert of works banned in Nazi-occupied Europe, employing both refugee and non-refugee musicians playing pieces by, among others, Egon Wellesz and Hans Gál (both resident in Britain during and after the war).

Early concerts also featured musicians such as violinists Arnold Rosé and Max Rostal, sopranos Claire Born, Irene Eisinger, and Emmy Heim, cellist Sela Trau, and pianists Edith Vogel, Franz Osborn and Peter Stadlen, to name just a few. The Society did not limit itself to the promotion of the work of musicians and composers from Continental Europe, arranging concerts featuring numerous British-born musicians and ensembles, as well as works by young Britons such as Pamela Harrison and Kenneth Leighton (in the 1950s) and Peter Maxwell Davies and Harrison Birtwistle (in the 1960s).

A further goal of the Society was the care and promotion of Austrian musical institutions and traditions, ranging from folk musics, classical and art musics, and light and popular music traditions.9

At times this entailed memorialisation of musicians like Tauber and Arnold Rosé (who died in Britain soon after the war’s end) or of figures like composer Arnold Schoenberg, closely associated with fin de siècle Vienna. It also involved celebration of important anniversaries such as the 1960 Mahler Centenary, an event commemorated in collaboration with the London County Council and Royal Festival Hall, with the Society contributing lectures by Ferdinand Rauter and record recitals.

Most significant, perhaps, was the mobilisation of Austrian musical institutions to and through Britain. The Society was instrumental, for instance, in bringing the Vienna State Opera Orchestra and the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra to London in the years immediately following World War II. The AAMS also organised tours throughout England and Scotland of ensembles like Toni Praxmair’s The Gay Tyrolese, a Tyrolean folkdance and music ensemble that toured under the auspices of the Society from 1957 until into the 1970s.

Even more enduring was the Society’s relationship with the Vienna Boys Choir, who gave around 1,200 AAMS-sponsored concerts throughout the United Kingdom from 1950 through to the 1990s. Indeed, it was these tours that perhaps best illuminate the lasting significance to British musical culture of the Anglo-Austrian Music Society, which found its centre in London, but reached all corners of Britain.

Further Reading

Brinson, Charmian. “Between Our Two Peoples’: The Archives of the Anglo-Austrian Society and the Anglo-Austrian Music Society.’ In Refugee Archives: Theory and Practice, Yearbook of the Research Centre for German and Austrian Exile Studies volume 9, edited by Andrea Hammel and Anthony Grenville, 95-108. Leiden: Brill, 2007.

Foster, Walter J., ed. If music be the food of love…: 50 Years of the Anglo-Austrian Music Society, 1942-1992. https://aams.org.uk/book.html

Haas, Michael. ‘Das Austrian Centre und die Anglo-Austrian Music Society.’ In Hans Gál und Egon Wellesz: Continental Britons, edited by Michael Haas and Marcus Patka, 86-95. Jüdischen Museum der Stadt Wien, 2004.

Levi, Erik. ‘The reception of Austro-German émigré musicians in the UK, 1933-1945.’ In …und werde in allen Lexika als ‘British’ aufgeführt, edited by G. Gruber, 15-26. Neumünster: von Böckel Verlag, 2015.

Rachel Pistol, ‘Refugees from National Socialism Arriving in Great Britain, 1933-1945.’ In Refugees, Relief and Resettlement. Farmington Hills: Gale Publishing, 2020. https://www.gale.com/intl/essays/rachel-pistol-refugees-national-socialism-great-britain-1933-1945#:~:text=In%20total%2C%20nearly%2010%2C000%20children,the%20east%20coast%20of%20England.

Scheding, Florian, et al. “Forum: ‘Who is British Music?’ Placing Migrants in National Music History.” Twentieth-Century Music 15, no. 3 (2018): 439-492.

Snowman, Daniel. The Hitler Émigrés: The Cultural Impact on Britain of Refugees from Nazism. London: Pimlico, 2002.

Stahrenberg, Carolin. “Ferdinand Rauter.” Last modified July 3, 2018. https://journals.publishing.umich.edu/mp/article/id/3852/

End Notes

1For more information on the internment of musicians during World War II and their activities in the camps, please see the ‘Internment: Musical Creativity in Confinement’ Story Map Collection. https://www.rcm.ac.uk/singingasong/storymaps/

2For more information about Rauter, his life and his creative and pedagogical activities, please see Jutta Raab Hansen’s ‘The Musician Ferdinand Rauter,’ and the video interview with Rauter’s daughter Andrea. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WWbCQcJBV4k

3For a first-hand recollection of Rauter and Lund’s initial meeting and early partnership, please see the video ‘Ferdinand Rauter and Engel Lund.’ https://youtu.be/VuMNhNStlSM

4For more information on some of Rauter’s musical activities in Britain and on his home life, please see the video interview with Dame Janet Baker, c. 45:58 https://youtu.be/lvAKsMtCHhQ

5For more information about the Amadeus Quartet and their activities, please see the ‘Amadeus Quartet: Forty years of global movement’ Story Map Collection. https://www.rcm.ac.uk/singingasong/storymaps/

6For more information, and the full contents of Vaughan Williams’ initial letter and Rauter’s response, please see an interview with Andrea Rauter, c. 1:00:58 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WWbCQcJBV4k

7For a detailed list of the Society’s concert programming from 1942 until 1962, please see ‘Two Decades of the Anglo-Austrian Music Society—Concerts 1942-1962’ based on my research with the Society’s archive.

8For more information on the Tauber Prize, See http://www.aams.org.uk/book.html

9For more information on the Society’s programming and activities including the 1950s tours of ‘Die Fledermaus,’ please see the video interview with Bernard Keeffe https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y_53-xk09Ok