Ferdinand Rauter, a musician, a “Renaissance man”, studied music and chemistry in Dresden from 1920. In 1929, he formed a partnership with the Danish singer Engel Lund, who had grown up in Iceland and had a unique talent to perform folk songs from all over the world in their original languages. Rauter came to live in Britain in 1929. He was interned as an enemy alien on the Isle of Man in 1940 and co-founded the Refugee Musicians Committee (1941), the Austrian Musicians Group and the Anglo-Austrian Music Society.

Author: Jutta Raab Hansen

1. Introduction

In 1933, the office of Josef Goebbels, the cultural commissar of the Nazis, invited pianist Ferdinand Rauter to give a concert with the singer Engel Lund in Dresden. Rauter replied: “Sorry, Mr. Goebbels. We are completely booked out until the end of the Third Reich.”1

The Austrian-born pianist Ferdinand Rauter, who was not a Jew, Engel Lund, a Danish/Icelandic mezzo-soprano, and their programme of “Songs of Many Lands” may have chimed well with the nationalistic music propaganda of the Nazis. Engel Lund was the first singer to come up with the idea of folk songs on concert stages, and since 1929 they had toured their multilingual programme all over Germany, Europe, and the United States. Their concerts always included a selection of German, Yiddish, and Icelandic Songs.

However, when the Nazis demanded the removal of the Yiddish songs from their programme, the singer-pianist duo did not want to compromise. So, they left the country and went to Denmark, where Lund’s family used to live. After moving out of Germany, Rauter and Lund gave concerts all over Europe, in the USA and Canada. Then, in 1935, the duo moved to England. Rauter continued to compose piano accompaniments for the songs they performed together until 1960. Two volumes, containing songs in fourteen languages with English translations by Ursula Vaughan-Williams and Eileen MacLeod, were published by Oxford University press in 1936 and 1949.2 In 1960, Engel Lund returned to Iceland, the country of her birth. She taught until her nineties at the Reykjavik conservatoire and died in 1996.

Ferdinand Rauter remained in Britain for the rest of his life. Open-minded and on excellent terms with both British and émigré musicians, he played a central role in émigré circles and helped to form the Anglo-Austrian Music Society, an important musical institution in Britain during and after WW2. After his marriage to Claire Kösten, his lively family home at Carlton Hill, north London, became a creative hub in a neighbourhood of refugee musicians, singers, writers, and artists, remembered beautifully in a 2015 oral history interview with Rauter’s daughter Andrea.3 Rauter acted as a mediator between refugee musicians and representatives of the government when times became difficult during WWII in Great Britain. His open house in London remained a famous place long after the war, where people met, became friends, made music, enjoyed meals together and discussed old and new projects.4

2. Rauter’s life 1902-1935

Ferdinand Rauter was born in 1902 in Klagenfurt in Austria. He received his early education from his father, a teacher for the blind. When Ferdinand was eleven years old, his father became head of the school for the blind in Aussig (now Ustí nad Labem in Czechia). The musically gifted boy played the piano for the students during their lessons or performed at school events. After qualifying for university, he went to Dresden, where he studied both music and chemistry: music at the Orchestra College of the Saxonian Orchestra and chemistry at Dresden Technical College. His first engagements brought him to Münster theatre in Northwest-Germany. He was both choir repetiteur and pianist for the dancer and choreographer Kurt Jooss and his ballet company, who also emigrated to England. Then, during a stay in Hamburg, Rauter by chance stood in as a pianist at a concert of Engel Lund. Years later Rauter remembered:

“I would never have thought, when I walked through a wood in 1929 where the mushrooms grew in order to get something for the pot, that half an hour later I would meet a lady who was called Engel Lund and became actually decisive for my whole life. She came up with Ravel’s Jewish Songs and I had never heard them. When she stood there and sang, something happened, which was quite new to me. She transformed herself, she became a rabbi. I heard God’s voice through her. It was so strong and so intense, that I said to her: ‘I think we should stay together all our lives.’”5

From this day on they stayed together until 1960, arranging and performing hundreds of folk songs in 21 different languages.6 Rauter added:

“The songs were such, that her reputation grew and after a rather short time she became known all over Germany. Then came the first tour to England, France, and Switzerland, then the whole Europe actually. In Hamburg, where we had started, the demand was so great, that in one week we had ten concerts.”7

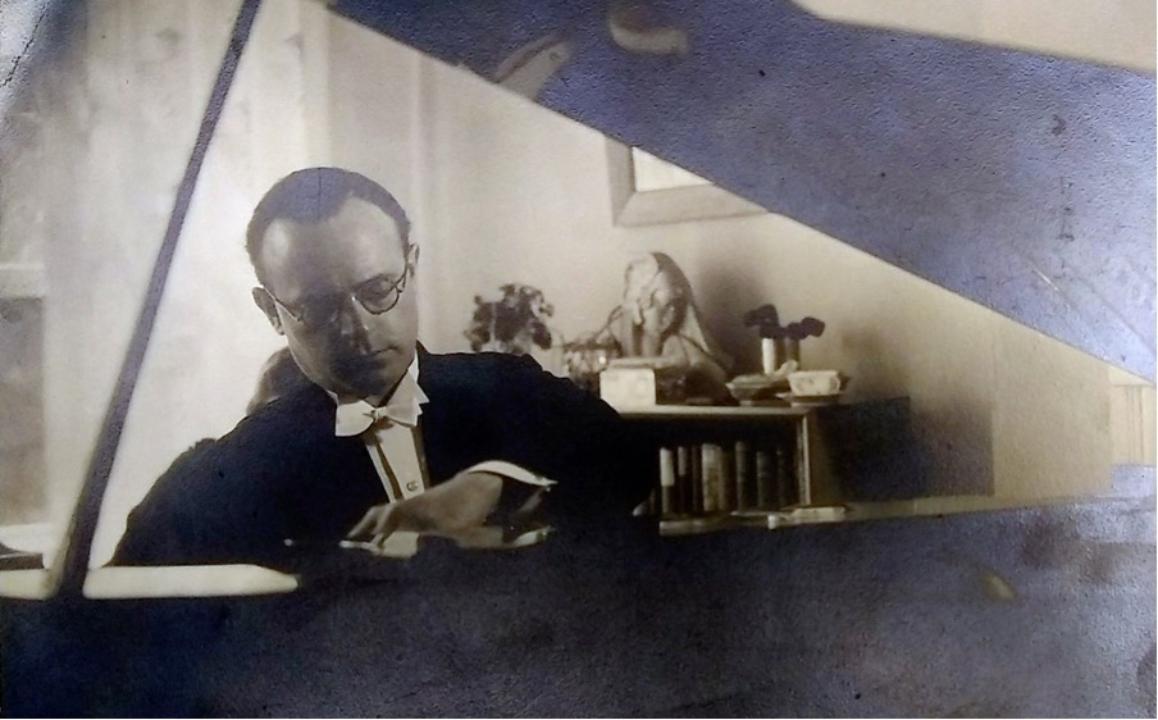

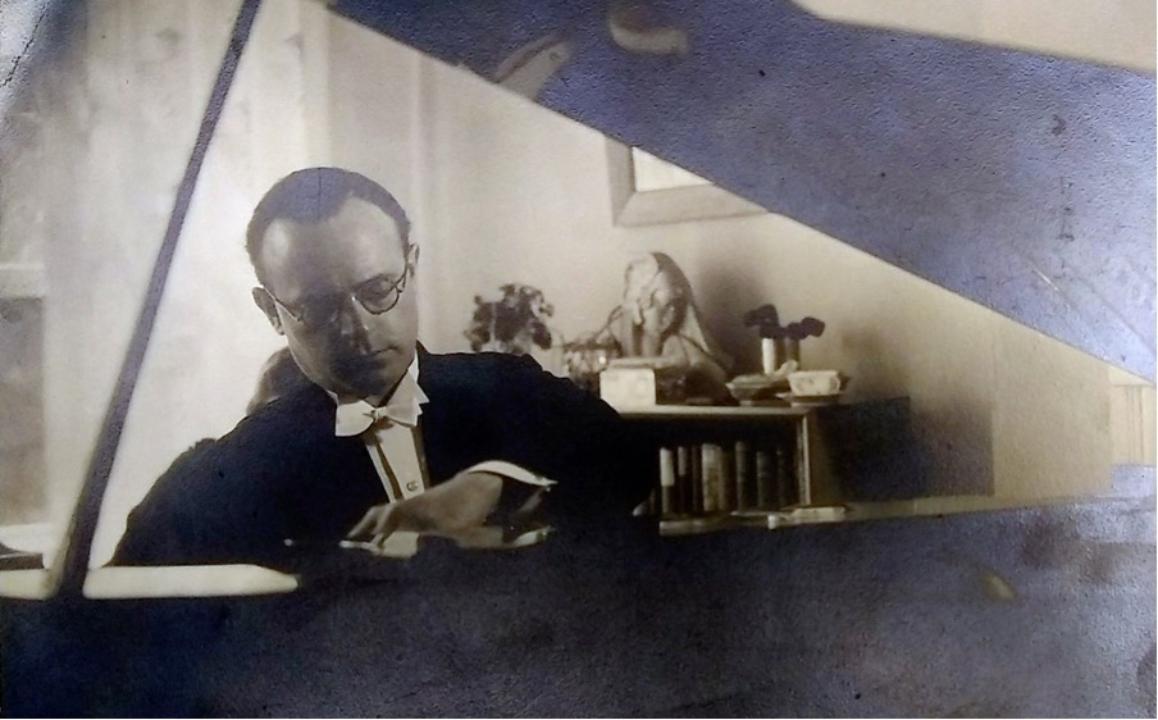

Engel Lund and Ferdinand Rauter, early 1930s, Universität Salzburg MMC

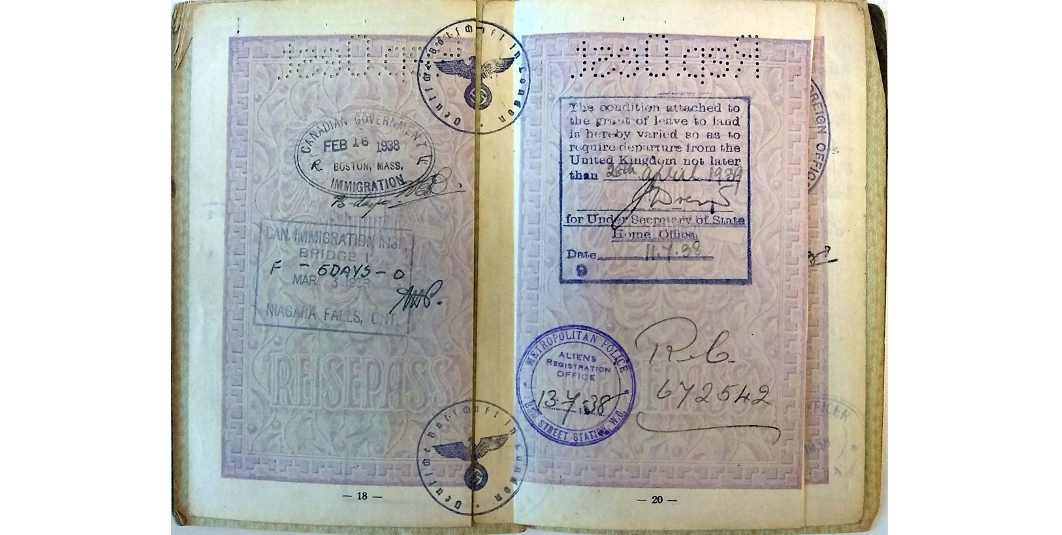

Even before moving to Britain, Lund and Rauter had been connected to the London-based concert agency Ibbs & Tillett. In 1935, they settled with friends in Clarendon Road in London’s Notting Hill area. After the Munich Treaty in September 1938 and the Wehrmacht’s occupation of the Sudetenland a day later, Rauter was cut off from his father, whom he was never to see again. On New Year’s Day 1938, Lund and Rauter embarked on a journey via Halifax to New York and returned at the end of March 1939. While still in the US, Rauter got the message about the “Anschluss” of Austria to the German Reich on 12 March. After asking several times, he was given a refugee-document by the Home Office. At the same time refugee organisations at the Austrian Office, the Austrian Centre and The Free German League of Culture provided thousands of refugees social and cultural support, meeting points as well as performing possibilities for both professional and many amateur musicians and singers. Rauter, who made acquaintances and friends easily, took part in many of these cultural activities, performed, and gave lectures. Before the war started there were about 78,000 refugees from Germany and Austria in Great Britain asking for asylum.8

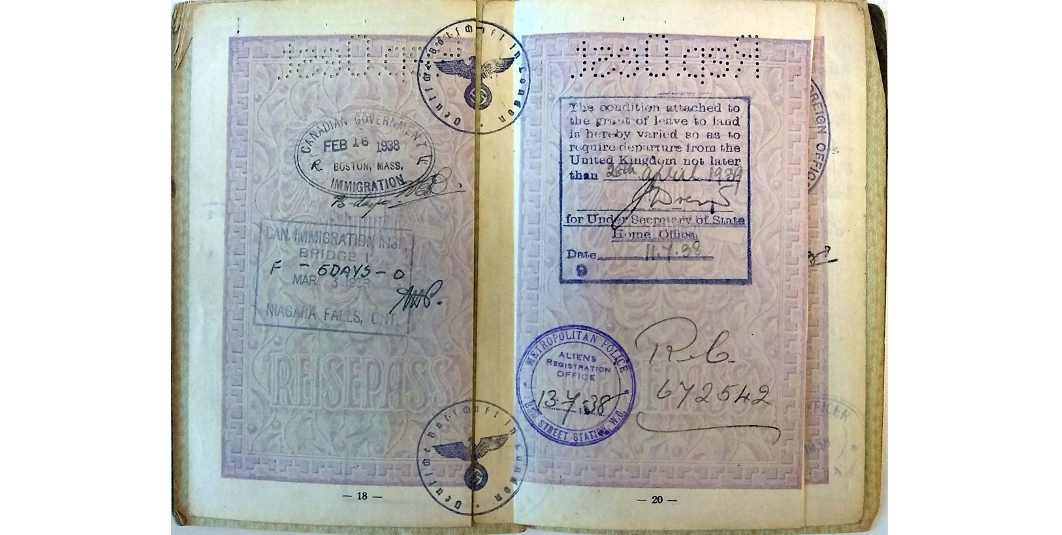

Pages from Rauter’s Reich-issued Passport with Stamps from Boston (USA) and Niagara Falls (Canada), February/March 1939, Universität Salzburg MMC

3. Internment and Release, 1940

On 3 September 1939, after the prime minister Neville Chamberlain announced that “…this country is at war with Germany”, Rauter and all German and Austrian refugees became enemy aliens. Tribunals set up at the beginning of the war stated the degree of threat for every single one of them. Yet surprisingly nothing happened for some weeks; it was the time of the “phoney war”. But after the “darkest hour” of the Battle of Dunkirk in June 1940, 27,700 were put under arrest. 8,000 of them were deported to camps in Canada and Australia.9

Rauter was locked up for 23 weeks in four different camps. The last one was Mooragh camp on the Isle of Man in the Irish Sea. Here the internees made the best of the situation with concerts, lectures and speeches given by academics, variously specialised.

In his various camps, Rauter played with young, gifted violinists such as Peter Schidlof and Norbert Brainin and gave solo performances and lectures on music. After the Home Office gave a White Paper for freeing “eminent musicians”, Rauter was one of the first refugees to be released in December 1940.10

To find a way to bring other musicians out of the camps, Rauter established the Musicians Refugee Committee, with help from Maud Karpeles, former assistant of the British specialist in folk music Cecil Sharp. On the managing board were prominent English musicians: Sir Hugh Allen, Ralph Vaughan Williams, Harriet Cohen, Myra Hess, Sir George Dyson and Sir Stanley Marchant. It aimed to bring musicians not only out from behind the barbed wire, but also helped them to make connections with teachers and gifted young musicians and provided funded access to colleges of music. For example, the violinist Peter Schidlof, freed in July 1941 and coached by Rauter, was accepted by Prof Max Rostal,11 a distinguished violin teacher from Berlin. Paul Hamburger from Vienna, a unique specialist of the Austrian idiom sought after by British singers, was given a grant to study at the Royal College of Music.12 Although the work restrictions for musicians still existed, exceptions were silently made. It seemed as if the “Blitz” of 1940-1941, when the Luftwaffe bombed London, Exeter, Liverpool, and other cities, brought their inhabitants closer together with their “unwanted guests”, as both were facing the same threat.

4. Meeting Claire Kösten

Shortly before leaving the Isle of Man, Rauter promised his Viennese fellow-refugee Josef Kösten that he would visit his family in London. And so it happened: Rauter met Josef’s 16-year-old daughter Claire Kösten and the two started seeing each other for the next four years. They went to the cinema and concerts, went on walks in Regent’s Park, played the piano together and Rauter introduced Claire to his best friends. The Viennese girl — both she and her brother saved by a Kindertransport ‒ was very intelligent and musical. She even got a grant for successfully finishing a piano teacher’s diploma at the Royal College of Music in London. Their acquaintance turned into friendship and love. Yet Rauter, 22 years Claire’s senior, wasn’t her parents’ favourite son-in-law for their only daughter, despite his support for her family.

5. National Gallery Concerts 1939-1945

A few weeks before WWII, the paintings of the National Gallery were taken to secret destinations, and eventually brought to Manod Quarry in North Wales.13 Seeing the empty rooms in the gallery, the pianist Myra Hess and the Trustees of the National Gallery decided to set up daily lunch-time concerts, mainly of chamber music. Both British and refugee musicians performed in these concerts: refugees from the countries invaded by the Wehrmacht, and refugees from Germany and the former Austria.

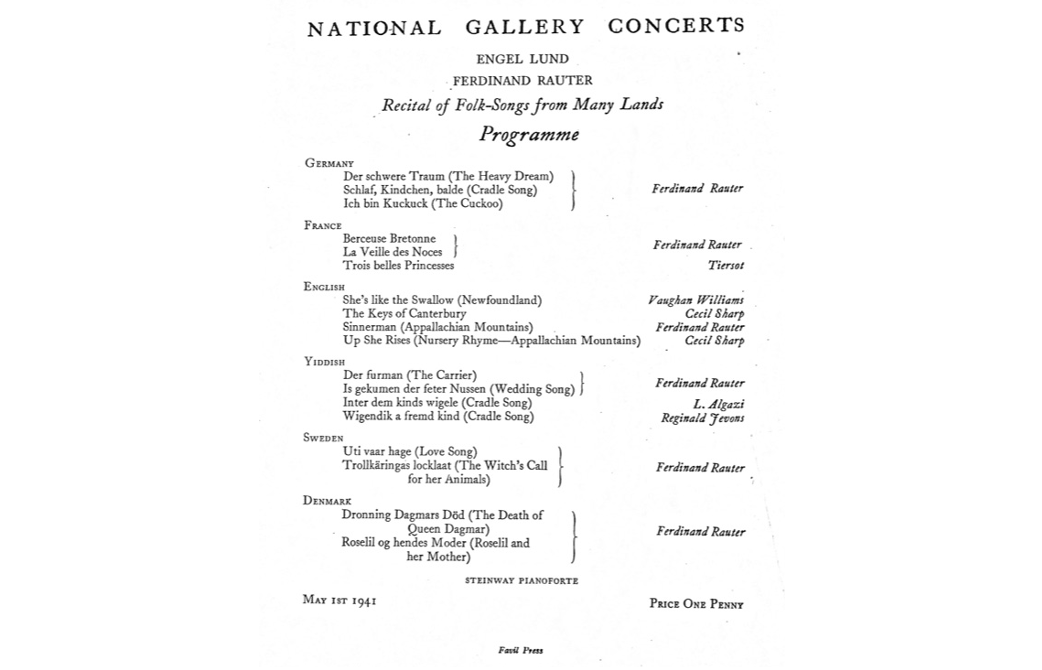

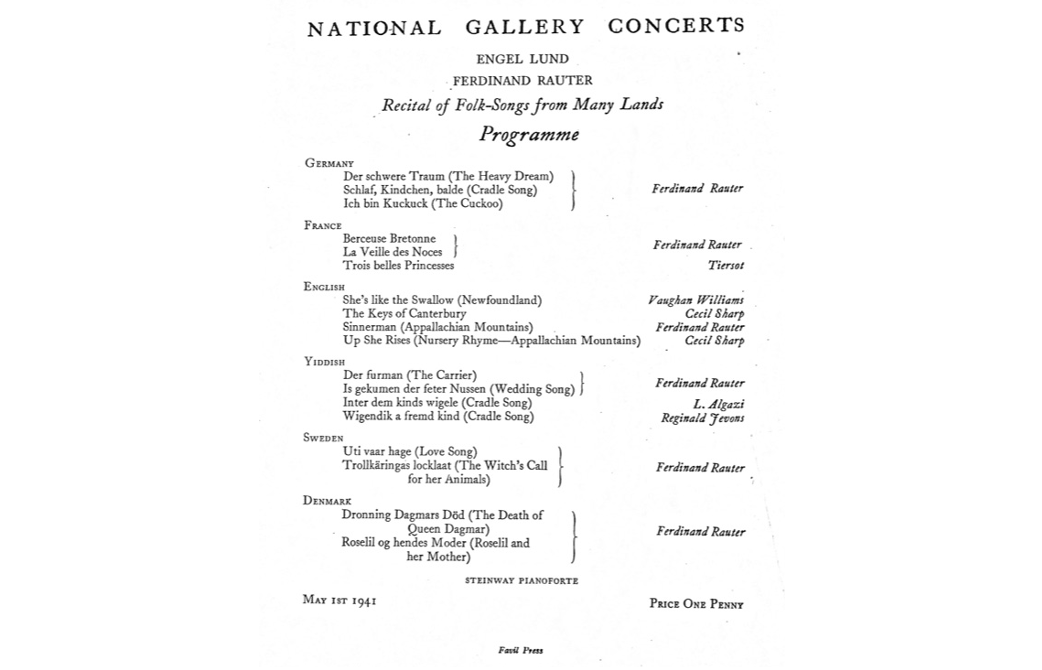

By April 1946, there had been 1698 concerts. The performing musicians received a modest salary, and the proceeds of the tickets went to the Musicians’ Benevolent Fund to support those British musicians without income. Engel Lund and Ferdinand Rauter performed their programme “Folk Songs of Many Lands” successfully 26 times by the end of 1945. Their songs also shed light on countries and people who had suffered deeply during the war: the Jewish and Yiddish ones especially touched the hearts of the public. Thanks to Myra Hess, German songs were sung in the original German, for example by Elena Gerhardt from Leipzig, although the BBC put a ban on broadcasting the German language on its home programmes throughout the war.14

Programme for 1 May 1941 National Gallery Concert, Universität Salzburg MMC

6. The war years 1940-1945

Back in London after his release from internment, Rauter continued playing as a soloist and chamber musician and accompanied Engel Lund’s songs for which he composed the pianoforte accompaniments. By now public opinion about refugee and “enemy” musicians had changed. Cleared of suspicion of being ‘fifth columnists’ and having been freed from internment, they were gradually allowed to perform in hospitals, factories, and military institutions.

Together with the lawyer and musicologist Hermann Ullrich and the pianist Georg Knepler, Rauter founded the Austrian Musicians Group (AMG). Without any payment the group performed at two Austrian exile organisations, the Austrian Centre, and the Austrian Office, both politically competing with each other.

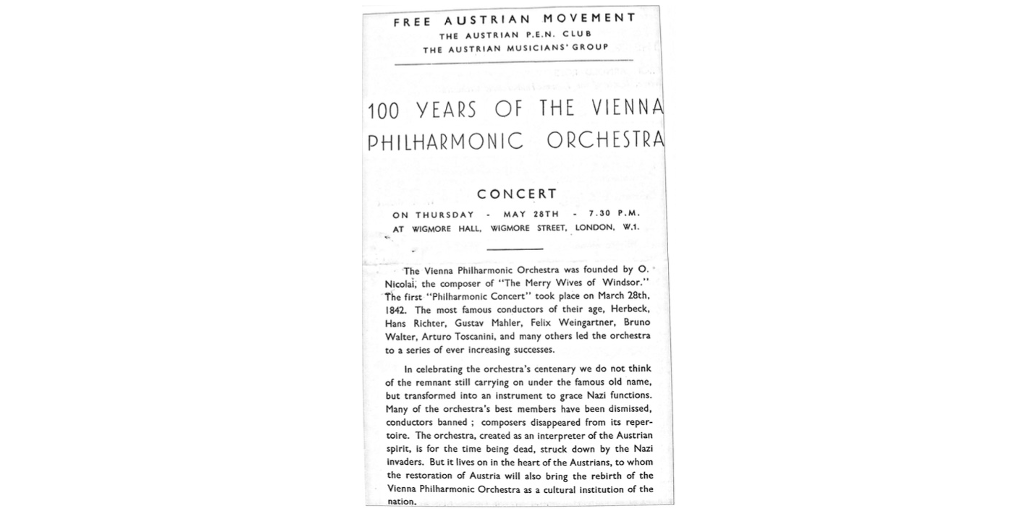

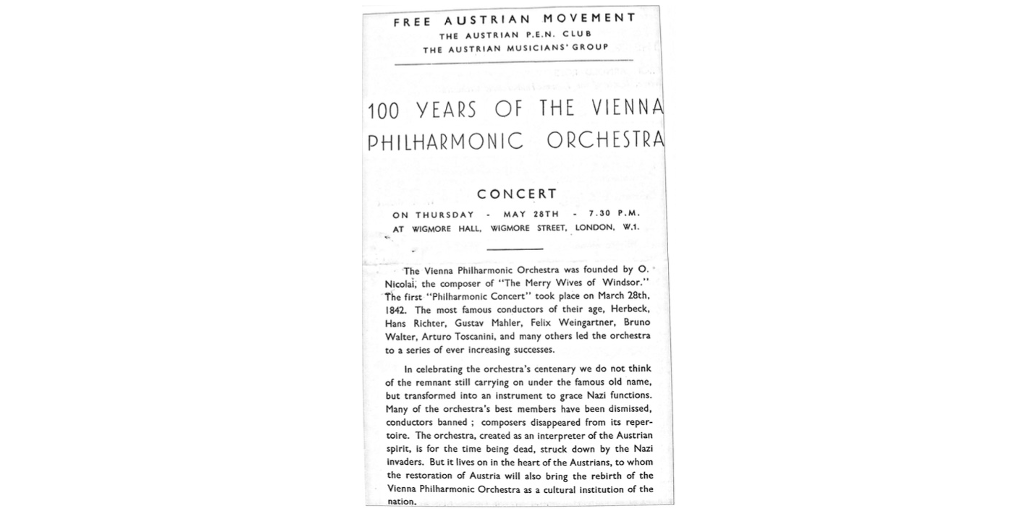

The first public event of the AMG was the commemoration of “100 Years of the Vienna Philharmonic” at Wigmore Hall on 28 May 1942. It was very well received in London. Arnold Rosé, an already frail man and a long-time leader of the once famous orchestra and his own Rosé String Quartet in Vienna, was the main attraction. He and his newly-formed string quartet performed music by Mozart, Wolf and Dvořák, with Ferdinand Rauter at the piano.15 In order to ensure the continued success of the AMG, Rauter tried to keep musical performances separate from political interests, so as to keep them more open to the British public. He also enlisted the help prominent British figures. One of them was the publisher, diplomat, and translator John Holroyd-Reece. Thus the “Society of Friends of the Austrian Musicians Group” was born.

Rauter and the British composer Ralph Vaughan Williams had already known and valued each other when the latter wrote his historically famous letter to the Austrian musician on 16 August 1942. Vaughan Williams straightforwardly expresses his apprehension that the Austrian refugee musicians could “impose their culture wherever they go as being the only one worth having”. He suggested to Rauter: “Become Englishmen ‒ assimilate our artistic ideals and then strengthen and fertilize them from your own incomparable art" (VWL1680). In his carefully worded response, Rauter then very politely shows his understanding of the British composer’s point of view and expresses his conviction that a harmonisation could be possible “through our union, to guide Austrian musicians to the great aim of mutual understanding and esteem, so that we work together as friends and brothers”(VWL1692).16

A few weeks later, on 15 December 1942, the first Anglo-Austrian Concert took place at the Wigmore Hall. It was then followed by privately-arranged concerts for fundraising and support from British people. Sir John Forsdyke,17 director of the British Museum and his wife, the Viennese violinist Dea Gombrich, sister of the art historian Sir Ernst Gombrich, invited the musicians and their guests into their private homes. The group changed its name to the Anglo-Austrian Music Society and gave concerts throughout the war, reaching out to and involving established British musicians in their concerts. Therefore, we find on printed programmes the names of Paul Hamburger, Mátyás Seiber, Max Rostal, Peter Pears, Benjamin Britten, Myra Hess, Gerald Moore, and others.18 After the war, a branch of the society was established in Vienna in order to facilitate the exchange of orchestras and students and the establishment of musical competitions. Over the years the society sponsored artists from both countries. Highlights included visits to Britain by the Vienna State Opera and Orchestra (1947), the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra (1948) and concert tours of the Vienna Boys Choir.19 The society also hosted the “Richard Tauber Singing Competition” every other year, awarding a Ferdinand Rauter Memorial Prize for piano accompaniment.20

Leaflet Announcing the first concert of the AMG, Universität Salzburg MMC (Music and Migration Collections, Ferdinand Rauter Papers, Box 4, Mappe 16)

7. Rauter’s Connection with Anthroposophy and the Christian Community

In the 1920s, while studying in Dresden, Rauter connected with the Christian Community and Rudolph Steiner’s Anthroposophy movement, a connection he retained all his life. In London he became a member of the Christian Community founded by the priest Alfred Heidenreich, ordained with his wife Marta Hemeran in the course held by Rudolf Steiner in Dornach in 1922.21 In London, Rauter often played the organ at the church of the Christian Community in Belsize Park. Interested in Steiner’s anthroposophy and natural sciences, he regularly went to lectures at the Steiner House in Marylebone. In July 1943 Rauter met the Viennese émigré paediatrician Dr König for the first time.22 About two years later König accepted Rauter’s offer to work with his therapeutic community project in Camphill, starting at the end of 1945.

8. Rauter in Camphill in Scotland ‒ 1945-1947

In December 1945, the Anglo Austrian Music Society, which Rauter knew was now in safe hands with its executive body, gave a farewell party for him. There was a buffet with caviar and salmon, cheese, and Viennese cakes, presents, speech by Home Office official E. N. Cooper and improvisation at the piano at the end. The next day, on 19 December, Rauter took the train to Scotland at King’s Cross.23

Rauter had been living in London for about ten years.24 The war, won by the allies, was over. He needed a break and distance from the hard times he had been through during the last six years. At the end of 1944, Claire Kösten had already taken the train to Camphill, near Aberdeen in Scotland, in the damp but beautiful countryside by the river Dee.25 At Camphill, about 20 Austrian (mainly Jewish) refugees with their own children, led by Dr Karl König from Vienna, had set up a therapeutic and educational project. König had worked and been educated at the anthroposophical clinic at Arlesheim (Switzerland), where he was taught by its founder Ita Wegman. She had been a close colleague of Rudolf Steiner’s during his last years until he died in 1925.

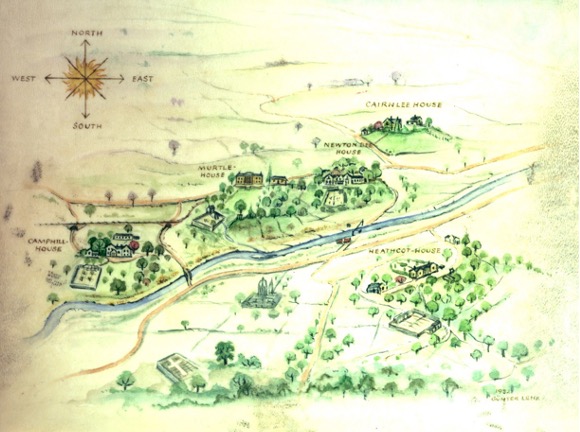

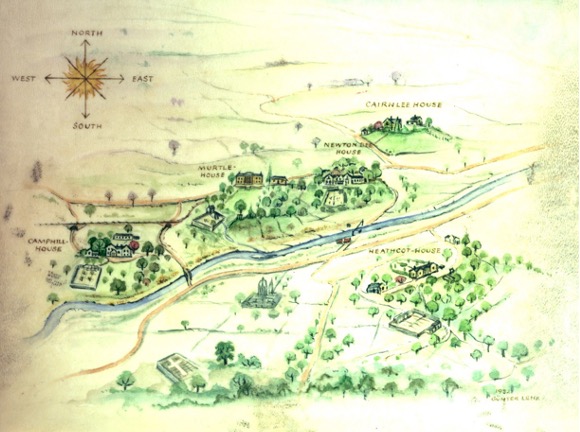

In April 1939, in Camphill, König set up his anthroposophical therapeutic community, caring especially for physically and mentally handicapped children, who were also part of a vivid Christian community. Four modest buildings, not far from each other, were added: Kirkton House, Murtle House, Cairnlee House and Heathcot House. In spartan conditions and poor heating, Claire Kösten worked (unpaid) with those children, teenagers, and young adults, being with them day and night. Camphill ‒ the starting-point and name for today’s worldwide movement ‒ aimed to approach those children individually at eye level, supporting their inner world and bringing out their hidden skills in order to discover the place to which they were best suited in community life.

Drawing of Camphill, Archive Andrea Rauter

Rauter stayed in Camphill until the end of June 1947. Claire and Rauter got married on 6 January 1946 and had a short honeymoon in the Lake District. Their daughter Andrea was born in December 1946. He interrupted his stay about ten times for some concerts with Engel Lund at the BBC, and for courses and workshops of the Christian Community in London and elsewhere in England, where he played the piano or gave lessons for children and adults. Working within the Camphill community and looking after the children meant that Rauter was also making repairs, doing the washing-up, being a nurse, cooking, and cleaning. In the evenings, Rauter delivered Steiner-lectures or readings and discussed anthroposophical subjects with the members. Rauter played the piano for the children, improvised, and composed for them. His duty was to prepare the children and stage plays to mark the events of the Christian calendar: He directed rehearsals, accompanied, and performed with the soloists and choirs (sometimes with Claire as well). After some months he worked as a teacher too. Sometimes, at house concerts, he accompanied the cellist Hans-Jürgen and the violinist Jürgen Hess, playing Beethoven Trios and sonatas by Mozart and Brahms. There wasn’t much time left for studying a new piano piece or setting songs for Engel Lund’s songbooks, especially after the baby had arrived. On 1 November 1946, Rauter returned to Camphill after ten days in London where he had had meetings with friends and mushroom specialists, and also with Adam Bittleston, a high-profile anthroposophist, and finally a successful concert with Engel Lund in Sheffield. We read in his diary: “By Taxi to Murtle. The reception is so overwhelming that I nearly cry. The children are as honestly and deeply happy as only children can be. Klärle’s joy and that of most of the others is wonderful. I immediately begin to prepare lunch and stay at home with Klärle who has a cold….”26

During his time in Camphill he tried to be a reliable and valuable member of the team and do all his tasks. But although Rauter struggled very hard to fit into the community and give up his former life, it didn’t work for him in the end. His place was London with all its opportunities and possibilities, with his friends, musicians and students who valued his musicianship, his open mind, social skills, diligence, friendship, his straightforward character, and his Austrian charm. In London, not in Camphill, he could develop his talents and ideas together with people around him. At the end of June 1947, he left with his family for London.27

9. Music Therapy

Nearly thirty years later, Rauter remembered having dedicated himself to music therapy in Camphill.28 Through his work at Camphill he helped to establish music therapy as a discipline. Karl König described in his essay “Music Therapy in Curative Education” (1959)29 how music therapy on the basis of Rudolf Steiner’s ideas had been improved in Camphill during the years after 1947. Rauter’s natural and individual approach to children with special needs, giving them respect, space and encouraging their listening and singing skills, paved the way. Later on, Anna Freud often sent Rauter children she knew he would find a way to approach via music.

10. London after 1947

Back in London, Rauter started anew at Carlton Hill. In 1948, his son Peter was born. Rauter continued with his teaching and performing as a soloist and chamber musician and he and Engel Lund continued to perform their folk songs of many lands. During the summer holidays the family travelled every year to visit relatives in Austria, enjoying the Austrian food and landscape. As a soloist and chamber musician, Rauter’s repertoire mainly remained “Austrian” for all of his life. Beethoven, Mozart, Schubert, Dvořák, Suk, but also J.S. Bach, whose music helped him in Camphill to find his own inner structure and that of the others. We still have to find out more in this direction.

Rauter’s home in London was a meeting place for many people: musicians, composers, chemists, mycologists, therapists, authors, and friends both from overseas and the UK. He became a household name in London, where he lived for more than 50 years.

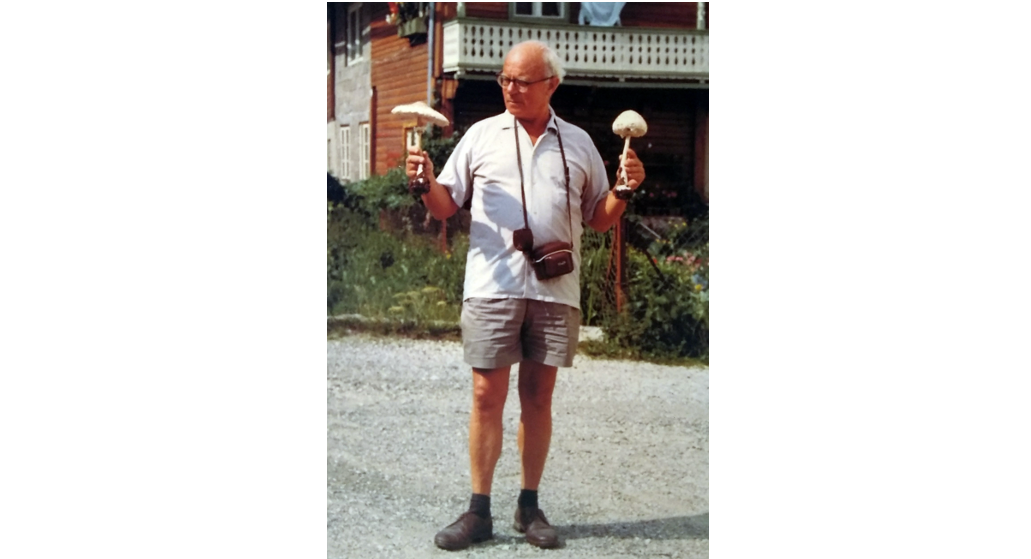

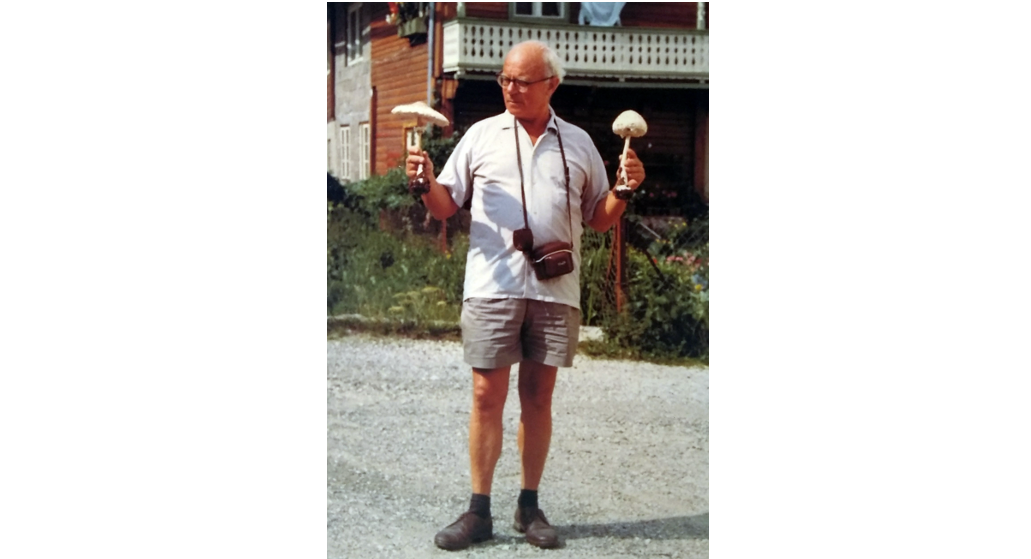

Among Rauter’s closest friends were Austrian refugees, including the composer Hans Gál, the musicologist-composer Egon Wellesz, and the violinist Max Rostal, who was the violin teacher of Norbert Brainin, Peter Schidlof and Siegmund Nissel. Notable British people whom Rauter befriended were the pianist Myra Hess, the composer Ralph Vaughan Williams and his wife Ursula Wood, as well as Maud Karpeles, the assistant of folk song collector Cecil Sharp, and Imogen Holst, the daughter of the composer Gustav Holst, both with their own country-wide networks in concert life and in politics. His family, being a pianist, a chamber musician, a teacher, anthroposophy, the Christian community, botany, mycology, and photography—all of these had been the pillars of the life of Ferdinand Rauter, who could be best characterized as “a Renaissance man”.

Since 1940, when Rauter had met the young Peter Schidlof on his way to interment, he coached him with special attention, as well as supporting Norbert Brainin and Siegmund Nissel to become outstanding violinists, and form the Amadeus Quartet. During the war Rauter had professional conversations with the experienced émigré-violinist Arnold Rosé (1883-1946), and they both loved to play privately together the works of Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert.

The singer Engel Lund remained for thirty years the most important artistic colleague in his life. And vice versa: they needed each other to bring out the the best of them mutually. Successfully they toured together in Europe and the USA.

Rauter on holiday holding mushrooms, undated, Universität Salzburg MMC (Universität Salzburg, Music and Migration Collections, Ferdinand Rauter Papers, Box 6, Mappe 12)